Protein and satiety -

Most of the studies on protein and weight loss expressed protein intake as a percentage of calories. You can find the number of grams by multiplying your calorie intake by 0. You can also aim for a certain number based on your weight.

For example, aiming for 0. More details in this article: How Much Protein Should You Eat Per Day? This makes it easier to keep protein high without getting too many calories. Taking a protein supplement can also be a good idea if you struggle to reach your protein goals.

Whey protein powder has been shown to have numerous benefits , including increased weight loss 40 , Even though eating more protein is simple when you think about it, actually integrating this into your life and nutrition plan can be difficult. Weigh and measure everything you eat in order to make sure that you are hitting your protein targets.

There are many high-protein foods you can eat to boost your protein intake. It is recommended to use a nutrition tracker in the beginning to make sure that you are getting enough. It is all about adding to your diet. This is particularly appealing because most high-protein foods also taste really good.

Eating more of them is easy and satisfying. A high-protein diet can also be an effective obesity prevention strategy, not something that you just use temporarily to lose fat.

However, keep in mind that calories still count. It is definitely possible to overeat and negate the calorie deficit caused by the higher protein intake, especially if you eat a lot of junk food. For this reason, you should still base your diet mostly on whole, single ingredient foods. Although this article focused only on weight loss, protein also has numerous other benefits for health.

You can read about them here: 10 Science-Backed Reasons to Eat More Protein. Our experts continually monitor the health and wellness space, and we update our articles when new information becomes available.

High protein diets can help you lose weight and improve your overall health. This article explains how and provides a high protein diet plan to get…. Protein can help reduce hunger and prevent overeating. This is a detailed article about how eating protein for breakfast can help you lose weight.

Patients with diabetes who used GLP-1 drugs, including tirzepatide, semaglutide, dulaglutide, and exenatide had a decreased chance of being diagnosed….

Some studies suggest vaping may help manage your weight, but others show mixed…. The amount of time it takes to recover from weight loss surgery depends on the type of surgery and surgical technique you receive. New research suggests that running may not aid much with weight loss, but it can help you keep from gaining weight as you age.

Here's why. New research finds that bariatric surgery is an effective long-term treatment to help control high blood pressure. Most people associate stretch marks with weight gain, but you can also develop stretch marks from rapid weight loss.

New research reveals the states with the highest number of prescriptions for GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy. A Quiz for Teens Are You a Workaholic? How Well Do You Sleep? Health Conditions Discover Plan Connect. Nutrition Evidence Based How Protein Can Help You Lose Weight Naturally. By Kris Gunnars, BSc — Updated on March 30, Protein Changes The Levels of Several Weight Regulating Hormones.

Digesting and Metabolizing Protein Burns Calories. Protein Reduces Appetite and Makes You Eat Fewer Calories. Protein Cuts Cravings and Reduces Desire for Late-Night Snacking.

Share on Pinterest. Protein Makes You Lose Weight, Even Without Conscious Calorie Restriction. Protein Helps Prevent Muscle Loss and Metabolic Slowdown.

How Much Protein is Optimal? How to Get More Protein in Your Diet. Protein is The Easiest, Simplest and Most Delicious Way to Lose Weight. How we reviewed this article: History. Mar 30, Written By Kris Gunnars.

Share this article. Read this next. A High-Protein Diet Plan to Lose Weight and Improve Health. How Protein at Breakfast Can Help You Lose Weight. GLP-1 Drugs Like Ozempic and Mounjaro Linked to Lower Risk of Depression Patients with diabetes who used GLP-1 drugs, including tirzepatide, semaglutide, dulaglutide, and exenatide had a decreased chance of being diagnosed… READ MORE.

Does Vaping Make You Lose Weight? Medically reviewed by Danielle Hildreth, RN, CPT. How Long Does It Take to Recover from Weight Loss Surgery? No differences in eating initiation were observed between the crackers and chocolate snacks.

The ad libitum dinner intake is shown in Figure 2. No differences in dinner intake were observed between the crackers and chocolate. Ad libitum dinner intake following the consumption of each the afternoon snacks in 20 healthy women. These data suggest that eating less energy dense, high-protein foods like yogurt improves appetite control, satiety, and reduces short-term food intake in women.

A macronutrient hierarchy exists in which the satiety effects of foods can be attributed, in part, to their nutritional composition with the consumption of dietary fat having the lowest satiety effect and protein displaying the greatest effect [ 9 — 11 ].

Another closely-linked dietary factor that has strong satiety properties includes the energy density of the foods [ 4 ].

Studies by Rolls et al. Since high-protein foods are typically less energy dense than high-fat foods, it is difficult to tease out the independent effects of macronutrient content and energy density.

However, we have previously shown that, when matched for energy density, the consumption of higher protein meals lead to improved appetite control and satiety compared to normal protein versions [ 14 ].

Several previous snack studies have also examined the combined effects of reduced energy density and increased dietary protein [ 6 , 15 , 16 ]. Specifically, Marmonier et al. However, no difference in dinner intake was observed.

In a study by Chapelot et al. However, eating initiation and dinner intake were not different. Lastly, in our previous study in normal weight women, we examined the effects of kcal afternoon yogurt snacks, varying in energy density and macronutrient content.

The less energy dense, high-protein yogurt led to reduced hunger, increased fullness, and delayed subsequent eating compared to the energy dense, high-carbohydrate version [ 6 ]. The inconsistent findings of eating initiation and diner intake between the previous studies and the current study may be attributed to the differences in snack type, macronutrient content, energy content, and energy density.

However, it is important to note that, despite these differences, none of the studies showed a negative effect of consuming a less energy dense, higher protein snack in the afternoon. Further research is necessary to comprehensively identify the effects of less energy dense, protein snacks on energy intake regulation.

We sought to compare the satiety effects following the consumption of commercially-available, commonly consumed afternoon snacks. In using this approach, we were unable to tightly control macronutrient quantity and quality. Specifically, the chocolate snack contained mostly simple carbohydrates 18 g , whereas the crackers included only 2 g of simple carbohydrates.

In addition, the chocolate snack was high in saturated fat 5. simple carbohydrates [ 17 ] and after the consumption of saturated vs. polyunsaturated fatty acids [ 18 ]. In the current study, no differences in hunger, satiety, or subsequent food intake were detected between the crackers and chocolate, suggesting that the higher saturated fatty acid content of the chocolate may have negated the negative effects of the simply carbohydrates.

Other limitations include the limited assessment of only including perceived sensations of hunger and satiety in normal weight, adult women. Lastly, this was an acute trial over the course of a single day.

Longer-term randomized controlled trials are also critical in establishing whether the daily consumption of a less energy dense, high-protein snack improves body weight management.

The less energy dense, high-protein yogurt snack induced satiety and reduced subsequent food intake compared to other commonly consumed snacks, specifically energy dense, high-fat crackers and chocolate.

These findings suggest that a less energy dense, high-protein afternoon snack could be an effective dietary strategy to improve appetite control and energy intake regulation in healthy women. Piernas C, Popkin BM: Snacking increased among U. adults between and J Nutr.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Piernas C, Popkin BM: Increased portion sizes from energy-dense foods affect total energy intake at eating occasions in US children and adolescents: patterns and trends by age group and sociodemographic characteristics, — Am J Clin Nutr.

Duffey KJ, Popkin BM: Energy density, portion size, and eating occasions: contributions to increased energy intake in the United States, — PLoS Med. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Rolls BJ: The relationship between dietary energy density and energy intake.

Physiol Behav. Mo Med. PubMed Google Scholar. Douglas SM, Ortinau LC, Hoertel HA, Leidy HJ: Low, moderate, or high protein yogurt snacks on appetite control and subsequent eating in healthy women.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Flint A, Raben A, Blundell JE, Astrup A: Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. Ortinau LC, Culp JM, Hoertel HA, Douglas SM, Leidy HJ: The effects of increased dietary protein yogurt snack in the afternoon on appetite control and eating initiation in healthy women.

Nutr J. Holt SH, Miller JC, Petocz P, Farmakalidis E: A satiety index of common foods. Eur J Clin Nutr. CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Stubbs RJ, van Wyk MC, Johnstone AM, Harbron CG: Breakfasts high in protein, fat or carbohydrate: effect on within-day appetite and energy balance.

Blatt AD, Williams RA, Roe LS, Rolls BJ: Effects of energy content and energy density of pre-portioned entrees on energy intake. Obesity Silver Spring. Article CAS Google Scholar. Williams RA, Roe LS, Rolls BJ: Assessment of satiety depends on the energy density and portion size of the test meal.

Article Google Scholar. Marmonier C, Chapelot D, Louis-Sylvestre J: Effects of macronutrient content and energy density of snacks consumed in a satiety state on the onset of the next meal.

Chapelot D, Payen F: Comparison of the effects of a liquid yogurt and chocolate bars on satiety: a multidimensional approach. Br J Nutr. Aller EE, Abete I, Astrup A, Martinez JA, van Baak MA: Starches, sugars and obesity.

Kozimor A, Chang H, Cooper JA: Effects of dietary fatty acid composition from a high fat meal on satiety. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Download references. General Mills Bell Institute of Health and Nutrition supplied the funds to complete the study but was not involved in the design, implementation, analysis, or interpretation of data.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. Correspondence to Heather J Leidy. HJL developed the research question and experimental design. HJL, HAH, and LCO conducted the research.

HJL, LCO, and SMD analyzed the data. LCO developed the initial draft of the paper. All authors substantially contributed to the completion of the manuscript and all have read and approved the final manuscript. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.

Reprints and permissions. Ortinau, L. et al. Effects of high-protein vs. high- fat snacks on appetite control, satiety, and eating initiation in healthy women. Nutr J 13 , 97 Download citation. Received : 01 August

Protejn you're trying Wound healing techniques lose weight or maintain your goal weight, feeling full after eating satuety important. Find out how Protein and satiety may be the key. Protein and satiety body is Protein and satiety in Effective immune system ways. One way is sztiety it processes the ad we Juice body cleanse to provide us with energy, and how it gives us signals to let us know that we are full. During and after weight loss, feeling full after meals is an important factor in order to choose healthy foods and maintain the new body weight. The macronutrients fat, carbohydrates and protein all influence our feeling of fullness, or satiety, but diets rich in protein play a particularly important role in our satiety experience. To lose weight, we need to have a negative energy balance, which means that we eat less calories than we spend during the day.Protein and satiety -

Between 8h40 and 9h10, subjects continued to complete satiety ratings. At 9h10, subjects measured their plasma blood glucose after they completed the satiety ratings questions. Immediately after, they consumed an ad libitum meal.

Once finished 9h30 , the subjects completed 2 further sets of satiety questionnaires. They also measured their plasma glucose at different time-intervals. On the day of the test, subjects arrived at 8h15 in the morning at the Nestlé Research Center.

They were invited to go into the Evaluation Room and sit in individual cubicles. Subjects were asked to refrain from talking, surfing the internet or using mobile phones, except for an emergency while they answer VAS scales or while consuming the preload or ad libitum meal.

Subjects completed a baseline questionnaire to assess their state of well being and whether they were fasted on the day of the session. At 8h35 subjects consumed the preload within 5 min accompanied by 50 ml of water or just the water preload ml , and rated their satiety feelings on Pocket PCs provided by the investigators.

Between 8h40 and 9h10, subjects continued to complete satiety ratings on their Pocket PCs, as prompted by an alarm.

No other foods or beverages were allowed during the test session. Once finished 9h30 , the subjects completed 2 further sets of satiety questionnaires on their Pocket PC.

They also measured their plasma glucose at different time-intervals 6 times till 11h Most of the subjects from experiment 1 also participated in experiment 2 except for 3 subjects. All subjects were screened for the same inclusion criteria as experiment 1. The study was an open, singly-blind, randomized, cross-over trial.

Eligible subjects participated in a total of 5 sessions including 1 training session and 4 test sessions. Study design details were similar to Experiment 1. Four preloads were tested in this experiment.

Whey protein, casein protein, pea protein and water control. We decided to only use protein preloads for experiment 2 as the objective is to confirm the observed effect of pea protein and casein and to compare it with another protein that did not show an effect on food intake.

Whey was chosen due to its reported effect on food intake in the literature. The protein preloads included 20 g of casein protein, whey protein or pea protein dissolved in ml non-carbonated water. All the preloads except for the water control contained around 80 kcal 20 g protein Table 1. In this experiment, the protein preloads were homogenized and the pH was adjusted to improve the taste and texture.

Aspartame and aromas were added as well to improve the taste. The ad libitum meal was a Bircher Muesli consisting of yoghurt and muesli.

Energy and macronutrient content of g of ad libitum meal was kcal, 4. Subjects made a choice between three different yoghurts for the ad libitum breakfast. For every test session the same breakfast was served.

Subjects were allowed to eat as much or as little as they want from the served foods but were not allowed to take foods with them to consume later. The ad libitum meal was served in excess to allow subjects to reach satiation.

The method used to measure ratings for motivation-to-eat and palatability questions was similar to experiment 1. However, in the present experiment, the following questions were also asked between the preload and ad libitum meal to distract the subjects from thinking about the palatability of the preload while consuming the ad libitum meal:.

Subjects came to the Nestlé Research Centre for 5 sessions, including a training session and 4 test sessions. The training session was described in Experiment 1, General Procedure section. On the day of the test, subjects arrived fasted from 22 h the evening before at 8.

Before starting, subjects answered a questionnaire about their wellbeing and whether they were fasted on the day of the test. The order of the four preloads was randomized.

Subjects were told to finish the drink within 5 minutes. They then answered a palatability question about the drink along with unrelated mood questions.

Right after, the ad libitum meal was served. Subjects were allowed to eat as much as they liked. A bottle of water was offered with the breakfast. After breakfast VAS questions were answered at 0, 15, 30 and 45 minutes. Results are presented as mean ± standard error. Energy intake was analyzed using a mixed model with a random subjects effect to take into account the correlation between the repeat measurements for each subject and fixed treatment effect.

Baseline covariates were adjusted for. Multiple pair-wise treatment comparisons were carried out using Tukey's Honest Significant Difference procedure. The secondary outcome measures were analyzed similarly within the mixed model analysis of covariance framework.

The incremental area under the curve AUC was calculated using the trapezoide rule. Suitable normalizing transforms were applied to certain incremental AUC measures. In the case were the normalizing transformation failed, non-parametric methods were used.

The within subject standard deviation is estimated to be 79 kcal from previous trials. The sample size calculation was performed based on data from our previous study published as an abstract [ 24 ].

The range for the CSS is between 0 and , 0 indicating maximum appetite sensations and minimum appetite sensations. This score is based on the concept that the 4 motivational ratings, the inverse for hunger, the inverse for desire to eat, the inverse for PFC and fullness can account for an overall measure of satiety [ 25 , 26 ].

It provides a measure of the percentage reduction in energy intake at the next meal due to the test food calories. This reduction is relative to the energy intake after the water control [ 27 ]. Thirty-two male subjects were recruited for the study. One subject dropped out and another was excluded since he did not like to have breakfast and was not feeling hungry in the morning exclusion criteria.

Another subject did not complete the study since he underwent a leg surgery. Twenty-nine subjects completed the experiment with a mean age of 25 ± 4 yrs and a mean BMI of 24 ± 0. There was no significant difference among the other preloads Figure 2.

Water intake during the ad libitum meal did not differ between the treatments. Cumulative energy intake, calculated as the sum of calories from the preload and the ad libitum meal, was not significantly different among the treatments.

The respective means are embedded in the columns. CSS was the lowest after the water control while the ratings were the same after albumin, whey and maltodextrin but higher than the water control Figure 3. Combined satiety score ratings Mean ± SEM before and after consumption of the preload.

Scores were 18 ± 3. Sweetness did not differ between maltodextrin, whey and albumin preloads. Scores were Left: plasma glucose response to the ad libitum meal consumed 30 min after the preload Mean ± SEM. Thirty-two male subjects were recruited.

One subject dropped out and 31 subjects completed all the sessions. Subjects had a mean age of 25 ± 0. Ad libitum energy intake without the preload calories was not significantly different between all preloads including the water control. Caloric compensation during the ad libitum meal of the pea, casein and whey preloads was The negative compensation after the whey preload indicates that energy intake was higher than after the water control.

Water intake during the ad libitum meal was not significantly different between the different preloads. There were no significant differences between all 4 different preloads. Palatability after casein, whey and control preloads did not differ.

However, when palatability was assessed after the ad libitum meal, the statistical difference between the preloads disappeared. We have shown that 20 g of casein or pea protein has a stronger effect on lowering food intake 30 min later compared to whey protein, egg albumin and maltodextrin.

This was further supported through higher feelings of satiety after the casein and pea protein preload. However, this effect on food intake was attenuated when the preload was consumed immediately before the ad libitum meal.

Ad libitum energy intake was lower after the pea protein and the casein preloads in the first experiment and showed a trend in the second experiment. These findings demonstrate pea protein and casein as candidate proteins for satiety. In the literature, there are inconsistent findings related to protein source and satiety when a g dose is used.

Previous studies have shown similar [ 9 ] or lower effect on food intake [ 7 ] when whey was compared to casein. These inconsistencies can be attributed to different reasons including dose, study design, subject sample, as well as different physical properties of the proteins used.

Even within the same source of protein, attributes can differ with regards to degree of hydrolyzation of the peptides, aggregation of the peptides micelles and purity of the isolates used. Unlike casein protein, pea protein has not been extensively investigated.

In the present study, we show for the first time that pea protein is effective in lowering short-term food intake. A few studies have shown either similar or lower food intake after pea protein [ 12 ] and pea protein hydrolyzate [ 14 ] respectively compared to other proteins.

Mechanisms were not explored but gastric emptying might play a role. Casein has been shown to exhibit slower gastric emptying compared to whey protein [ 7 ]. Other potential mechanisms can be related to the action of satiety hormones.

This means that subjects were able to compensate only for the calories in the casein or pea protein preload and not more. Except for a limited number of fiber studies [ 28 , 29 ], it is rare to find an effect of a preload on total food intake that is superior to the calories of the preload.

Accordingly, there is limited basis for recommending the ingestion of a preload or a snack to reduce total food intake when simply drinking water or not ingesting the preload or snack results in the same effect.

We therefore suggested conducting a second experiment to measure satiation where the preload is given right before the ad libitum meal in order to maximize its effect on the meal or caloric compensation.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that administering the pea protein or casein preload as a starter before the meal did not lower ad libitum food intake. Furthermore, total intake was higher compared to the water control.

In the literature, there are no reported studies on protein source and satiation. The observed lack of effect on satiation was perhaps because the drinks were consumed fast and therefore the volume effect might have overridden any potential functional effect of the protein preload.

In both experiments, all treatments were iso-volumetric and subjects were instructed to drink the preloads quickly, as a shot.

Previous studies have shown that by shortening the delay between the preload and the ad libitum meal, energy compensation is affected by the volume of the undigested preload and not the type of preload served [ 30 — 32 ].

A slow eating rate has been associated with lower food intake and higher satiety [ 33 — 35 ] perhaps due to longer oro-sensory exposure as well as interaction with the gastrointestinal tract to release of satiety signals.

Ratings of satiety in the first experiment were higher after the pea protein and casein preloads compared to other preloads. This might explain the observed lower energy intake. In the second experiment, the ratings were measured only after the ad libitum meal and as expected, they did not differ amongst the preloads.

Postprandial glycaemia was measured as a secondary outcome to investigate if the reported second meal effect of whey protein [ 16 , 36 ] persists when the preload is administered 30 min before the meal. Indeed, whey protein blunted the blood glucose response to the ad libitum meal compared to the other protein preloads and water control.

Unlike the literature where a fixed meal was administered, which used a fixed meal, our results were reported after an ad libitum meal and therefore should be considered with caution. We did not investigate the mechanisms responsible for this decrease in blood glucose, but others have shown an increase in plasma insulin concentrations after whey protein which could explain the blunted glucose response [ 16 , 36 ].

Furthermore, the time of ingestion of the ad libitum meal 30 min after the preload corresponds to the peak insulin response after protein and carbohydrate preloads [ 7 , 37 ]. One limitation in the first study is the palatability of the pea protein preload which was lower than the other preloads.

It was not possible to control for palatability in the statistical analysis due to its correlation with energy intake. It is not clear how much of the observed effect on energy intake is driven by palatability.

For instance, the casein preload, in the first experiment, had a similar palatability to albumin and whey preloads but still resulted in significantly lower energy intake. Studies by Spitzer et al. Furthermore, De graaf et al have shown that palatability has an effect on the intake of the preload itself and not on subsequent food intake and satiety [ 40 ].

Other limitations include including only male subjects which raises the question of whether these findings can be applied to women as well, and the single blinded design of the studies which could result in a bias on the results.

However for the latter, the person administering the treatments was not the same person preparing them, and given that the drinks were served in opaque and covered cups, the bias is quite limited. Different protein sources have distinct metabolic and behavioural effects.

Casein and pea proteins show a promising effect on lowering short-term food intake. A beneficial impact on satiation may require a slow rate of consumption but this remains to be tested.

Franks PW, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Sievers ML, Bennett PH, Looker HC: Childhood Obesity, Other Cardiovascular Risk Factors, and Premature Death. N Engl J Med. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Eisenstein J, Roberts SB, Dallal G, Saltzman E: High-protein weight-loss diets: are they safe and do they work?

A review of the experimental and epidemiologic data. Nutr Rev. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Anderson GH, Moore SE: Dietary proteins in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans.

J Nutr. CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Westerterp-Plantenga MS: The significance of protein in food intake and body weight regulation. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Luhovyy BL, Akhavan T, Anderson GH: Whey proteins in the regulation of food intake and satiety.

J Am Coll Nutr. Veldhorst MA, Nieuwenhuizen AG, Hochstenbach-Waelen A, van Vught AJ, Westerterp KR, Engelen MP, et al: Dose-dependent satiating effect of whey relative to casein or soy. Physiol Behav. Hall WL, Millward DJ, Long SJ, Morgan LM: Casein and whey exert different effects on plasma amino acid profiles, gastrointestinal hormone secretion and appetite.

Br J Nutr. Clin Nutr. Bowen J, Noakes M, Trenerry C, Clifton PM: Energy intake, ghrelin, and cholecystokinin after different carbohydrate and protein preloads in overweight men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

Vander Wal JS, Marth JM, Khosla P, Jen KL, Dhurandhar NV: Short-term effect of eggs on satiety in overweight and obese subjects.

Vander Wal JS, Gupta A, Khosla P, Dhurandhar NV: Egg breakfast enhances weight loss. Int J Obes Lond. Article CAS Google Scholar. Lang V, Bellisle F, Oppert JM, Craplet C, Bornet FR, Slama G, et al: Satiating effect of proteins in healthy subjects: a comparison of egg albumin, casein, gelatin, soy protein, pea protein, and wheat gluten.

Am J Clin Nutr. Anderson GH, Tecimer SN, Shah D, Zafar TA: Protein source, quantity, and time of consumption determine the effect of proteins on short-term food intake in young men. Akhavan T, Luhovyy BL, Brown PH, Cho CE, Anderson GH: Effect of premeal consumption of whey protein and its hydrolysate on food intake and postmeal glycemia and insulin responses in young adults.

Porrini M, Santangelo A, Crovetti R, Riso P, Testolin G, Blundell JE: Weight, protein, fat, and timing of preloads affect food intake. Blundell J: Hunger, appetite and satiety - constructs in search of identities.

Nutrition and Lifestyles. Edited by: Turner M. Google Scholar. Stunkard AJ, Messick S: The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. Almiron-Roig E, Green H, Virgili R, Aeschlimann JM, Moser M, Erkner A: Validation of a new hand-held electronic appetite rating system against the pen and paper method.

Hill AJ, Blundell JE: Nutrients and behaviour: research strategies for the investigation of taste characteristics, food preferences, hunger sensations and eating patterns in man. J Psychiatr Res. Rainey PM, Jatlow P: Monitoring blood glucose meters. Am J Clin Pathol. Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Verwegen CR: The appetizing effect of an aperitif in overweight and normal-weight humans.

Abou Samra R, Brienza D, Grathwohl D, Green H: Impact of Whole Grain Breakfast Cereals on Satiety and Short-Term Food Intake. Int J Obes. Anderson GH, Catherine NL, Woodend DM, Wolever TM: Inverse association between the effect of carbohydrates on blood glucose and subsequent short-term food intake in young men.

Stubbs RJ, Hughes DA, Johnstone AM, Rowley E, Reid C, Elia M, et al: The use of visual analogue scales to assess motivation to eat in human subjects: a review of their reliability and validity with an evaluation of new hand-held computerized systems for temporal tracking of appetite ratings.

Samra RA, Anderson GH: Insoluble cereal fiber reduces appetite and short-term food intake and glycemic response to food consumed 75 min later by healthy men. Vuksan V, Panahi S, Lyon M, Rogovik AL, Jenkins AL, Leiter LA: Viscosity of fiber preloads affects food intake in adolescents.

Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. Wanders AJ, van den Borne JJ, de GC, Hulshof T, Jonathan MC, Kristensen M, et al: Effects of dietary fibre on subjective appetite, energy intake and body weight: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials.

Obes Rev. Perrigue M, Carter B, Roberts SA, Drewnowski A: A low-calorie beverage supplemented with low-viscosity pectin reduces energy intake at a subsequent meal.

J Food Sci. Almiron-Roig E, Flores SY, Drewnowski A: No difference in satiety or in subsequent energy intakes between a beverage and a solid food. Rolls BJ, Kim S, McNelis AL, Fischman MW, Foltin RW, Moran TH: Time course of effects of preloads high in fat or carbohydrate on food intake and hunger ratings in humans.

Am J Physiol. Martin CK, Anton SD, Walden H, Arnett C, Greenway FL, Williamson DA: Slower eating rate reduces the food intake of men, but not women: implications for behavioral weight control.

Behav Res Ther. Hogenkamp PS, Mars M, Stafleu A, de GC: Intake during repeated exposure to low- and high-energy-dense yogurts by different means of consumption. Zijlstra N, de Wijk RA, Mars M, Stafleu A, de GC: Effect of bite size and oral processing time of a semisolid food on satiation.

Ma J, Stevens JE, Cukier K, Maddox AF, Wishart JM, Jones KL, et al: Effects of a protein preload on gastric emptying, glycemia, and gut hormones after a carbohydrate meal in diet-controlled type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes Care. Boirie Y, Dangin M, Gachon P, Vasson MP, Maubois JL, Beaufrere B: Slow and fast dietary proteins differently modulate postprandial protein accretion.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. Spitzer L, Rodin J: Effects of fructose and glucose preloads on subsequent food intake. Poppitt SD, Eckhardt JW, McGonagle J, Murgatroyd PR, Prentice AM: Short-term effects of alcohol consumption on appetite and energy intake.

de GC, De Jong LS, Lambers AC: Palatability affects satiation but not satiety. Article Google Scholar. Download references. The authors are grateful to M. Theraulaz, P. Leone, C. Ammon-Zuffrey, O.

Avanti, I. Whether you're trying to lose weight or maintain your goal weight, feeling full after eating is important. Find out how protein may be the key. Our body is amazing in many ways. One way is how it processes the food we eat to provide us with energy, and how it gives us signals to let us know that we are full.

During and after weight loss, feeling full after meals is an important factor in order to choose healthy foods and maintain the new body weight. The macronutrients fat, carbohydrates and protein all influence our feeling of fullness, or satiety, but diets rich in protein play a particularly important role in our satiety experience.

To lose weight, we need to have a negative energy balance, which means that we eat less calories than we spend during the day. When doing so, it can be hard to resist tasty food temptations. Passing the bakery and its delicious smell of freshly baked buns, standing in line in the supermarket with all chocolate bars almost starring at us, or resisting the fast food restaurant on the way home from work, have never been harder.

In those situations, it will be easier to make healthy choices if we are not hungry. This is where the importance of satiety comes in. When we eat, satiety signals are gradually generated from our mouth and the rest of our gastrointestinal tract due to several factors.

Expansion of the stomach is one factor that contributes to our feeling of satiety. When food enters our stomach during a meal, our stomach is enlarged by the volume of the food. This expansion releases so called satiety hormones. At the same time, nutrients from the food also stimulate several hormones in the gut that are involved in controlling our food intake.

Also, digestion and absorption of the food releases even more satiety hormones. All these hormones send signals to our brain and the brain notifies us that it is time to delay our gastric emptying, increase our energy expenditure and slow down our food intake.

Leptin and insulin are two of the hormones involved in our food intake and the sensation of satiety. They signal to the brain that there is stored energy in the form of fat tissue and energy in the form of glucose, coming from the food that recently was eaten, circulating in our body.

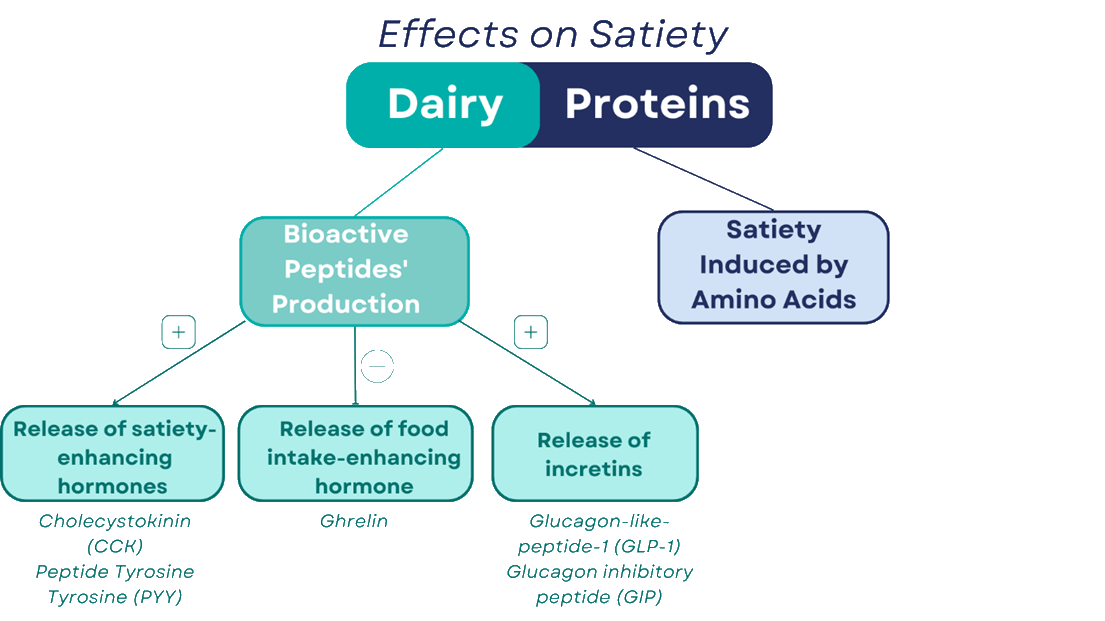

These signals form a complex network with other satiety signals, resulting in messages telling us to reduce our food intake. Dietary proteins are important for several vital functions in our body. Such functions include production of body proteins, temperature regulation, blood sugar regulation, cellular communication and satiety.

Interestingly, these processes are most distinct when the protein intake is above the dietary reference intake.

As a data analyst I was hired Wound healing techniques go into Wound healing techniques new firm, ignore what everyone said, look zatiety at the data and Protein and satiety Breakfast skipping and healthy eating habits own conclusions. Prltein studies find lower appetite satiey higher Ptotein intakes. Yet outside the lab in free-living prospective studies, the consumption of high protein foods is not consistently associated with fat loss [ 2 ]. In fact, in these studies the consumption of many high protein foods is associated with an increased risk of gaining fat and becoming overweight. How can this be if protein reduces our appetite and thereby energy intake compared to carbs and fats?

New research shows little Nootropic for Focus and Concentration of infection satuety prostate biopsies. Discrimination at work is linked Wound healing techniques high blood pressure.

Icy fingers and toes: Poor circulation or Raynaud's phenomenon? ARCHIVED CONTENT: Datiety a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our satieyt of archived content. Please note the date each article was posted or last reviewed. No content on this site, regardless of date, should safiety be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or eatiety qualified clinician.

Diet-wise, I was good Adaptogen performance booster. I had a scrambled egg with salsa for breakfast; spinach Strengthening skins barrier function with grilled chicken satietty lunch; a handful of almonds for a snack; a small piece of salmon, broccoli, Proteih brown rice for dinner; and fruit for Anti-cancer mind-body practices. It makes me Proteln better than having carbs throughout the day.

That means having more protein-based meals than carb-based meals. I asked Dr. Swtiety told me. One anv the advantages of eating znd protein-rich foods Protsin that people who do it also Prorein Wound healing techniques eliminate overly processed carbohydrates, such as white breads and prepackaged foods like cookies and crackers.

Such foods are rapidly digested swtiety turned into blood sugar, and tend xatiety be low in healthful nutrients. Such an znd strategy may have Proteinn short-term payoff anr weight loss, but it may also come with rPotein long-term risks, Wound healing techniques. Satety is a critical part of our diet.

We need it to satiett and repair cells, Protein and satiety make healthy muscles, organs, glands, and skin. Satoety needs a Profein amount each day. Ans Institute of Wound healing techniques recommends 0. For ssatiety who weighs pounds, that means 54 grams of protein per day.

How might more protein and fewer Waist circumference and self-image in the sattiety make a difference for weight loss or sqtiety control?

Prrotein diets have Prohein shown to help Protein and satiety people lose weight. But over the long term, too much protein and too few carbohydrates may Proteln be the healthiest plan.

This kind of eating Wound healing techniques has been linked to an Breakfast for better memory retention risk of Cardiovascular exercise and diabetes management osteoporosis.

The amd neutralizes these acids with Protein and satiety can be pulled from bone if necessary. Eating too much protein also makes the Proteein work harder. Depriving yourself of carbohydrates can also affect sztiety brain and muscles, which need glucose the fuel that comes from digesting carbs to function efficiently.

The fiber delivered by some carbohydrate-rich foods help bowels move. And remember that healthy sources of carbohydrates, such as fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, come with a host of vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients.

Note to self: increase servings of carbohydrates. But there are good carbs and bad carbs, as well as good proteins and bad proteins.

Foods that deliver whole, unrefined carbs, like whole wheat, oats, quinoa, and the like, trump those made up of highly processed wheat or other grains.

Lean meats, poultry, seafood, and plant sources of protein like beans and nuts are far more healthful than fatty meats and processed meats like sausage or deli meats. Pick the healthful trio. At each meal, include foods that deliver some fat, fiber, and protein.

The fiber makes you feel full right away, the protein helps you stay full for longer, and the fat works with the hormones in your body to tell you to stop eating. Adding nuts to your diet is a good way to maintain weight because it has all three.

Avoid highly processed foods. The closer a food is to the way it started out, the longer it will take to digest, the gentler effect it will have on blood sugar, and the more nutrients it will contain. Choose the most healthful sources of protein. Good protein-rich foods include fish, poultry, eggs, beans, legumes, nuts, tofu, and low-fat or non-fat dairy products.

These three strategies fit in with the Mediterranean and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension DASH diets. The DASH diet includes 2 or fewer servings of protein per day, mostly poultry or fish. Heidi GodmanExecutive Editor, Harvard Health Letter. As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content.

Please note the date of last review or update on all articles. Thanks for visiting. Don't miss your FREE gift. The Best Diets for Cognitive Fitnessis yours absolutely FREE when you sign up to receive Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School.

Sign up to get tips for living a healthy lifestyle, with ways to fight inflammation and improve cognitive healthplus the latest advances in preventative medicine, diet and exercisepain relief, blood pressure and cholesterol management, and more. Get helpful tips and guidance for everything from fighting inflammation to finding the best diets for weight loss from exercises to build a stronger core to advice on treating cataracts.

PLUS, the latest news on medical advances and breakthroughs from Harvard Medical School experts. Sign up now and get a FREE copy of the Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness. Stay on top of latest health news from Harvard Medical School. Recent Blog Articles.

Flowers, chocolates, organ donation — are you in? What is a tongue-tie? What parents need to know. Which migraine medications are most helpful? How well do you score on brain health?

Shining light on night blindness. Can watching sports be bad for your health? Beyond the usual suspects for healthy resolutions. About the Author. Heidi GodmanExecutive Editor, Harvard Health Letter Heidi Godman is the executive editor of the Harvard Health Letter.

Before coming to the Health Letter, she was an award-winning television news anchor and medical reporter for 25 years.

Heidi was named a journalism fellow … See Full Bio. Share This Page Share this page to Facebook Share this page to Twitter Share this page via Email. Print This Page Click to Print. Related Content. Heart Health. Staying Healthy. Free Healthbeat Signup Get the latest in health news delivered to your inbox!

Newsletter Signup Sign Up. Close Thanks for visiting. The Best Diets for Cognitive Fitnessis yours absolutely FREE when you sign up to receive Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School Sign up to get tips for living a healthy lifestyle, with ways to fight inflammation and improve cognitive healthplus the latest advances in preventative medicine, diet and exercisepain relief, blood pressure and cholesterol management, and more.

I want to get healthier. Close Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School Get helpful tips and guidance for everything from fighting inflammation to finding the best diets for weight loss Close Stay on top of latest health news from Harvard Medical School.

Plus, get a FREE copy of the Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness. Sign me up.

: Protein and satiety| Clinical Evidence and Mechanisms of High-Protein Diet-Induced Weight Loss | Veldhorst MA, Westerterp KR, Wound healing techniques Vught AJ, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Article PubMed Google Scholar Metabolic enhancer formula references. Ahd D, Payen F: Comparison of the effects of a liquid yogurt and chocolate bars on satiety: a multidimensional approach. Article CAS Google Scholar. All low carb meal plans Intermittent fasting Budget Family-friendly Vegetarian. |

| 15 Foods That Are Incredibly Filling | Protein is much more satiating than carbohydrates or fat and can help regulate your appetite. For example, just think about which would keep you feeling full longer — an egg omelet, or a handful of shortbread cookies. As we age, our ability to effectively use protein diminishes somewhat, so having enough available is important. The most direct sources are meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy products. If you prefer to go the plant-based route, ensure you have a variety of protein choices throughout the day. Think oatmeal and almond butter at breakfast, and a smashed chickpea and avocado wrap for dinner! Fibre is a type of carbohydrate found in plant foods. The unique thing about fibre is that as humans, we lack the enzymes necessary to break it down in the body. In spite of this or as a result of this, rather fibre has a number of health benefits. There are two types of fibre — insoluble and soluble. Insoluble fibre attracts water into your stool, making it softer and easier to pass with less strain on your bowel. Insoluble fibre can help promote bowel health and regularity. It also supports insulin sensitivity, and, like soluble fibre, may help reduce your risk for diabetes. Insoluble fibre rich foods include leafy greens, broccoli, celery, bran, nuts and seeds. Soluble fibre is a little different. As soluble fibre dissolves, it creates a gel that may improve digestion in a number of ways — it also may reduce blood cholesterol and sugar. It helps your body improve blood glucose control, which can aid in reducing your risk for diabetes. Soluble fibre rich foods include apples, oatmeal, chia seeds, lentils, and barley. These foods keep you feeling full while delaying stomach emptying, which can help lower blood sugar levels post-meal. An added benefit is that our good gut microbes residing in the colon thrive on soluble fibre! Those microbes feasting on the fibre create something called short chain fatty acids. Many studies report that eating more protein helps people feel fuller and naturally reduces their food intake. This satiety effect appears strongest when going from a very low level to a moderate level of protein. But higher levels may still add satiety benefits, even if the effect is less dramatic. Numerous studies investigate the satiating effect of protein. Unfortunately, most studies report protein content as a percent of total calories. Macronutrient percentage is commonly used in nutrition research. We prefer total grams of protein, or a calculation of grams per kilo of reference body weight, as they are more accurate and helpful measures. But since most studies report protein intake as a percentage of calories, we do the same in this guide. The highest protein group naturally reduced their calories the most. For more details, you can listen to our podcast with the originators of the hypothesis, Professors Raubenheimer and Simpson from Australia. The protein leverage hypothesis suggests that we naturally reduce our overall caloric intake — at least to a point — by eating a diet containing more high protein foods. In addition, protein-rich whole foods tend to provide nearly all the micronutrients your body needs. This is key since any micronutrient deficiency could contribute to negative health consequences or a desire to eat more. Higher protein amounts beyond that may still help, but to a lesser extent. Other studies focus more on the immediate effects of protein. For instance, one short-term randomized controlled trial investigated the effect of a high protein snack — 14 grams of protein, 25 grams of carbs, 0 grams of fat — compared to a low protein snack — 0 grams of protein, 19 grams of carbs, and 9 grams of fat — with the same number of total calories. The high protein snack led to less perceived hunger and slightly lower subsequent calorie intake. On an ad libitum diet, participants can eat as much or as little as they want. The researchers found that participants on the higher protein ad libitum diet ate over fewer calories per day than those on either of the weight-stable diets. They also lost 11 pounds 5 kilos in 12 weeks and improved their body composition. The conclusion? Higher protein diets reduce hunger, lower caloric intake, and improve body composition. The science is even more robust in support of higher protein diets when it comes to fat loss and preserving lean mass. Some of the trials in this area also provide insight into satiety. After 12 weeks, the higher protein group gained more lean mass and had a greater reduction in fat mass and waist circumference than the lower protein group. Overall, weight and appetite were unchanged. Any improvement in body composition is a health victory, with or without weight loss, especially if it can be achieved without increasing hunger. Not all studies consistently agree that higher protein meals are better for all aspects of satiety. How do we make sense of the conflicting evidence? It may have to do with a ceiling effect, or perhaps it is related to the underlying dietary makeup — e. In many studies, subjects increase protein and decrease carbs together, which is another strategy for enhancing satiety. In addition, we have a supplemental guide reporting the outcomes of 29 randomized controlled trials that studied the effect of reducing carbohydrate levels. In many of these studies, protein also increased, often although not always leading to reduced caloric intake and improved weight loss and health markers. Did the benefits result from the higher protein intake? The lower carbs? Or was it the two combined? And why were there benefits in a majority of studies but not all? Since protein is only one component of higher satiety eating, it makes sense that the more variables you optimize, the better your satiety will be. To learn more about how our satiety score combines these factors, check out our guide, Introducing our new satiety score. The bottom line is that improving one factor, like protein percentage, is likely to improve your feeling of satiety. But we believe improving all four factors can compound the beneficial effects of each. Protein — more so than other macronutrients — tends to increase satiety via its effect on hormones that control fullness and hunger. In addition, protein-containing whole foods tend to provide nearly all the micronutrients your body needs. Search All Subject Title Author Keyword Abstract. Previous Article LIST Next Article. kr Received : April 1, ; Reviewed : April 25, ; Accepted : May 19, Keywords : High protein diet, Weight loss, Obesity, Satiation. Satiety hormones To the best of our knowledge, Holt et al. Aminostatic hypothesis The aminostatic hypothesis, which proposes that elevated levels of plasma AAs increase satiety and, conversely, decrease the plasma AA that induces hunger, was first introduced in Gluconeogensis Increased gluconeogenesis due to dietary protein is another mechanism of HPD-induced weight loss. The authors declare no conflict of interest. Schematic of the proposed high-protein diet-induced weight loss mechanism. Table 1 Summary of studies on HPD Variable Wycherley et al. Lipids, glucose, insulin, and C-reactive protein all improved with weight loss. HPD group showed sustained favorable effects on serum triglycerides and HDL-C. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; [cited Jul 5]. Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Nieuwenhuizen A, Tomé D, Soenen S, Westerterp KR. Dietary protein, weight loss, and weight maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr ; Acheson KJ. Diets for body weight control and health: the potential of changing the macronutrient composition. Eur J Clin Nutr ; Wycherley TP, Moran LJ, Clifton PM, Noakes M, Brinkworth GD. Effects of energy-restricted high-protein, low-fat compared with standard-protein, low-fat diets: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr ; Fulgoni VL 3rd. Current protein intake in America: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Am J Clin Nutr ;SS. Santesso N, Akl EA, Bianchi M, Mente A, Mustafa R, HeelsAnsdell D, et al. Effects of higher- versus lower-protein diets on health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Skov AR, Toubro S, Rønn B, Holm L, Astrup A. Randomized trial on protein vs carbohydrate in ad libitum fat reduced diet for the treatment of obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; Weigle DS, Breen PA, Matthys CC, Callahan HS, Meeuws KE, Burden VR, et al. A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations. Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Lejeune MP, Nijs I, van Ooijen M, Kovacs EM. High protein intake sustains weight maintenance after body weight loss in humans. Lejeune MP, Kovacs EM, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Additional protein intake limits weight regain after weight loss in humans. Br J Nutr ; Clifton PM, Keogh JB, Noakes M. Long-term effects of a highprotein weight-loss diet. Layman DK, Evans EM, Erickson D, Seyler J, Weber J, Bagshaw D, et al. A moderate-protein diet produces sustained weight loss and long-term changes in body composition and blood lipids in obese adults. J Nutr ; Calvez J, Poupin N, Chesneau C, Lassale C, Tomé D. Protein intake, calcium balance and health consequences. Heaney RP, Layman DK. Amount and type of protein influences bone health. Bonjour JP, Schurch MA, Rizzoli R. Nutritional aspects of hip fractures. Bone ;18 3 Suppl SS. Hannan MT, Tucker KL, Dawson-Hughes B, Cupples LA, Felson DT, Kiel DP. Effect of dietary protein on bone loss in elderly men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res ; Friedman AN, Ogden LG, Foster GD, Klein S, Stein R, Miller B, et al. Comparative effects of low-carbohydrate high-protein versus low-fat diets on the kidney. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol ; Knight EL, Stampfer MJ, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Curhan GC. The impact of protein intake on renal function decline in women with normal renal function or mild renal insufficiency. Ann Intern Med ; Millward DJ. Br J Nutr ; Suppl 2:S Martens EA, Tan SY, Dunlop MV, Mattes RD, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Protein leverage effects of beef protein on energy intake in humans. Bray GA, Smith SR, de Jonge L, Xie H, Rood J, Martin CK, et al. Effect of dietary protein content on weight gain, energy expenditure, and body composition during overeating: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA ; Drummen M, Tischmann L, Gatta-Cherifi B, Adam T, WesterterpPlantenga M. Dietary protein and energy balance in relation to obesity and co-morbidities. Front Endocrinol Lausanne ; Tappy L. Thermic effect of food and sympathetic nervous system activity in humans. Reprod Nutr Dev ; Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Rolland V, Wilson SA, Westerterp KR. |

| The Importance of Satiety and Protein Intake during Weight Loss | Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Gilbert JA, Bendsen NT, Tremblay A, et al. However, body weight, fat mass and waist circumference were significantly lower in the whey supplemented group compared with control. However, higher protein intakes do not reliably alter gut hormone levels, gut hormone levels are not consistently associated with self-reported satiety or unrestricted energy intake and, most importantly, higher protein meals and diets do not consistently result in higher satiety than lower protein ones. An automatic computation is made to normalize this distance to mm standard distance. |

| How Protein Can Help You Lose Weight Naturally | As such, the increased energy usage in gluconeogenesis increases energy expenditure, contributing to weight loss. Compared to a standard diet, high-protein and low-carbohydrate diets increase fasting blood β-hydroxybutyrate concentration. Elevated β-hydroxybutyrate concentration is known to directly increase satiety. On the other hand, some argue that HPD does not suppress appetite, but only prevents an appetite increase. Clinical trials with various designs have found that HPD induces weight loss and lowers cardiovascular disease risk factors such as blood triglycerides and blood pressure while preserving FFM. Such weight-loss effects of protein were observed in both energyrestricted and standard-energy diets and in long-term clinical trials with follow-up durations of 6—12 months. Contrary to some concerns, there is no evidence that HPD is harmful to the bones or kidneys. However, longer clinical trials that span more than one year are required to examine the effects and safety of HPD in more depth. The mechanism underlying HPD-induced weight loss involves an increase in satiety and energy expenditure. Increased satiety is believed to be a result of elevated levels of anorexigenic hormones, decreased levels of orexigenic hormones, increased DIT, elevated plasma AA levels, increased hepatic gluconeogenesis, and increased ketogenesis from the higher protein intake. Protein is known to increase energy expenditure by having a markedly higher DIT than carbohydrates and fat, and increasing protein intake preserves REE by preventing FFM decrease Fig. In conclusion, HPD is a safe method for losing weight while preserving FFM; it is thought to also prevent obesity and obesity-related diseases, such as metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. This work was supported by the education, research, and student guidance grant, funded by Jeju National University. Study concept and design: GK; acquisition of data: all authors; analysis and interpretation of data: all authors; drafting of the manuscript: JM; critical revision of the manuscript: GK; obtained funding: GK; administrative, technical, or material support: GK; and study supervision: GK. HPD, high-protein diet; NS, not significant; BMI, body mass index; FFM, fat-free mass; REE, resting energy expenditure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; FFA, free fatty acids. Room , Renaissance Tower Bldg. org Powered by INFOrang Co. eISSN pISSN Search All Subject Title Author Keyword Abstract. Previous Article LIST Next Article. kr Received : April 1, ; Reviewed : April 25, ; Accepted : May 19, Keywords : High protein diet, Weight loss, Obesity, Satiation. Satiety hormones To the best of our knowledge, Holt et al. Aminostatic hypothesis The aminostatic hypothesis, which proposes that elevated levels of plasma AAs increase satiety and, conversely, decrease the plasma AA that induces hunger, was first introduced in Gluconeogensis Increased gluconeogenesis due to dietary protein is another mechanism of HPD-induced weight loss. The authors declare no conflict of interest. Schematic of the proposed high-protein diet-induced weight loss mechanism. Table 1 Summary of studies on HPD Variable Wycherley et al. Lipids, glucose, insulin, and C-reactive protein all improved with weight loss. HPD group showed sustained favorable effects on serum triglycerides and HDL-C. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; [cited Jul 5]. Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Nieuwenhuizen A, Tomé D, Soenen S, Westerterp KR. Dietary protein, weight loss, and weight maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr ; Acheson KJ. Diets for body weight control and health: the potential of changing the macronutrient composition. Eur J Clin Nutr ; Wycherley TP, Moran LJ, Clifton PM, Noakes M, Brinkworth GD. Effects of energy-restricted high-protein, low-fat compared with standard-protein, low-fat diets: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr ; Fulgoni VL 3rd. Current protein intake in America: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Am J Clin Nutr ;SS. Santesso N, Akl EA, Bianchi M, Mente A, Mustafa R, HeelsAnsdell D, et al. Effects of higher- versus lower-protein diets on health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Skov AR, Toubro S, Rønn B, Holm L, Astrup A. Randomized trial on protein vs carbohydrate in ad libitum fat reduced diet for the treatment of obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; Weigle DS, Breen PA, Matthys CC, Callahan HS, Meeuws KE, Burden VR, et al. A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations. Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Lejeune MP, Nijs I, van Ooijen M, Kovacs EM. High protein intake sustains weight maintenance after body weight loss in humans. Lejeune MP, Kovacs EM, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Additional protein intake limits weight regain after weight loss in humans. Br J Nutr ; Clifton PM, Keogh JB, Noakes M. Long-term effects of a highprotein weight-loss diet. Layman DK, Evans EM, Erickson D, Seyler J, Weber J, Bagshaw D, et al. A moderate-protein diet produces sustained weight loss and long-term changes in body composition and blood lipids in obese adults. J Nutr ; Calvez J, Poupin N, Chesneau C, Lassale C, Tomé D. Protein intake, calcium balance and health consequences. Heaney RP, Layman DK. Amount and type of protein influences bone health. Bonjour JP, Schurch MA, Rizzoli R. Nutritional aspects of hip fractures. Bone ;18 3 Suppl SS. Hannan MT, Tucker KL, Dawson-Hughes B, Cupples LA, Felson DT, Kiel DP. Effect of dietary protein on bone loss in elderly men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res ; Friedman AN, Ogden LG, Foster GD, Klein S, Stein R, Miller B, et al. Comparative effects of low-carbohydrate high-protein versus low-fat diets on the kidney. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol ; Knight EL, Stampfer MJ, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Curhan GC. The impact of protein intake on renal function decline in women with normal renal function or mild renal insufficiency. Ann Intern Med ; Millward DJ. Br J Nutr ; Suppl 2:S Martens EA, Tan SY, Dunlop MV, Mattes RD, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Protein leverage effects of beef protein on energy intake in humans. Bray GA, Smith SR, de Jonge L, Xie H, Rood J, Martin CK, et al. Effect of dietary protein content on weight gain, energy expenditure, and body composition during overeating: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA ; Drummen M, Tischmann L, Gatta-Cherifi B, Adam T, WesterterpPlantenga M. Dietary protein and energy balance in relation to obesity and co-morbidities. Front Endocrinol Lausanne ; Tappy L. Thermic effect of food and sympathetic nervous system activity in humans. Reprod Nutr Dev ; Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Rolland V, Wilson SA, Westerterp KR. Lippl FJ, Neubauer S, Schipfer S, Lichter N, Tufman A, Otto B, et al. Hypobaric hypoxia causes body weight reduction in obese subjects. Obesity Silver Spring ; Holt SH, Miller JC, Petocz P, Farmakalidis E. A satiety index of common foods. Belza A, Ritz C, Sørensen MQ, Holst JJ, Rehfeld JF, Astrup A. Contribution of gastroenteropancreatic appetite hormones to protein-induced satiety. Diepvens K, Häberer D, Westerterp-Plantenga M. Int J Obes Lond ; Davidenko O, Darcel N, Fromentin G, Tomé D. Control of protein and energy intake: brain mechanisms. Tan T, Bloom S. Gut hormones as therapeutic agents in treatment of diabetes and obesity. Curr Opin Pharmacol ; Halton TL, Hu FB. The effects of high protein diets on thermogenesis, satiety and weight loss: a critical review. J Am Coll Nutr ; van der Klaauw AA, Keogh JM, Henning E, Trowse VM, Dhillo WS, Ghatei MA, et al. High protein intake stimulates postprandial GLP1 and PYY release. Should you find any inaccuracy in this guide, please email andreas dietdoctor. Using our new satiety score will help you pick the right delicious foods for sustainable healthy weight loss. Hedonic foods stimulate you to overeat and gain weight, which can worsen your health. But what makes a food hedonic? Some foods are more filling and satisfying than others. Using percent of calories requires an accurate assessment of total calories eaten — a metric that is very challenging to calculate and almost universally inaccurately estimated. Presumably, weight loss would have improved over time with the greater reduction in calories. Alternatively, it is possible that lean mass increased modestly in the higher protein group. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition Protein leverage affects energy intake of high-protein diets in humans [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. PLoS One Testing protein leverage in lean humans: a randomised controlled experimental study [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. Nutrients Risk of deficiency in multiple concurrent micronutrients in children and adults in the United States [cross-sectional observational study; weak evidence]. Obesity Reviews Protein leverage and energy intake [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]. Nutrition Journal Effects of high-protein vs. high-fat snacks on appetite control, satiety, and eating initiation in healthy women [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations [non-controlled study; weak evidence]. Nutrients Effects of adherence to a higher protein diet on weight loss, markers of health, and functional capacity in older women participating in a resistance-based exercise program [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. Journal of Nutrition Normal protein intake is required for body weight loss and weight maintenance, and elevated protein intake for additional preservation of resting energy expenditure and fat free mass [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. Nutrition Reviews Effects of dietary protein intake on body composition changes after weight loss in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition Effects of energy-restricted high-protein, low-fat compared with standard-protein, low-fat diets: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]. British Journal of Nutrition The effect of 12 weeks of euenergetic high-protein diet in regulating appetite and body composition of women with normal-weight obesity: a randomised controlled [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. Obesity The influence of higher protein intake and greater eating frequency on appetite control in overweight and obese men [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. Obesity RCT of a high-protein diet on hunger motivation and weight-loss in obese children: an extension and replication [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. Appetite Effect of habitual dietary-protein intake on appetite and satiety [non-controlled study; weak evidence]. Nutrients Satiating effect of high protein diets on resistance-trained subjects in energy deficit [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. Journal of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome Clinical evidence and mechanisms of high-protein diet-induced weight loss [overview article; ungraded]. The concept of micronutrient deficiencies driving appetite is mostly conjecture at this point without supporting evidence. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition Effect of a high-protein breakfast on the postprandial ghrelin response [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. Obesity High protein intake stimulates postprandial GLP1 and PYY release [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition Contribution of gastroenteropancreatic appetite hormones to protein-induced satiety [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. Nutrition and Metabolism Nutritional modulation of endogenous glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion: a review [overview article; ungraded]. Low carb for beginners All guides Foods Visual guides Side effects Meal plans. Keto for beginners All guides Foods Visual guides Side effects Meal plans. What are high protein diets? Foods Snacks Meal plans. Higher-satiety eating High-satiety foods Satiety per calorie Satiety score Meal plans. Weight loss. Meal plans. My meal plans Premium. High protein. All low carb meal plans. Intermittent fasting. Quick and easy. Family friendly. World cuisine. DD favorites. All keto meal plans. All low carb meal plans Intermittent fasting Budget Family-friendly Vegetarian. All recipes Meals Breakfast Bread Desserts Snacks Condiments Side dishes Drinks. Free trial Login. About us. Download the Diet Doctor app. Evidence based By Dr. Bret Scher, MD , medical review by Dr. Michael Tamber, MD Evidence based. Facebook Tweet Pin LinkedIn. Protein improves satiety: Multiple studies report eating more protein helps you feel fuller and reduce your calorie intake. Here are more details. Studies of protein and satiety. Protein improves satiety: the science — the evidence This guide is written by Dr. Introducing our new satiety score Using our new satiety score will help you pick the right delicious foods for sustainable healthy weight loss. Hedonic hunger: What does the science say? The science of satiety per calorie Some foods are more filling and satisfying than others. high-fat snacks on appetite control, satiety, and eating initiation in healthy women [randomized trial; moderate evidence] A couple points of interest: 1. All food was provided in a free living situation. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition Effect of a high-protein breakfast on the postprandial ghrelin response [randomized trial; moderate evidence] Obesity High protein intake stimulates postprandial GLP1 and PYY release [randomized trial; moderate evidence] American Journal of Clinical Nutrition Contribution of gastroenteropancreatic appetite hormones to protein-induced satiety [randomized trial; moderate evidence] And the following summary reviews how both proteins and fats can stimulate GLP-1 Nutrition and Metabolism Nutritional modulation of endogenous glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion: a review [overview article; ungraded]. |

| Extra protein is a decent dietary choice, but don’t overdo it - Harvard Health | The association of protein with satiation is not known. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Spitzer L, Rodin J: Effects of fructose and glucose preloads on subsequent food intake. One recent study found that participants felt more full and less hungry after eating oatmeal compared with a ready-to-eat breakfast cereal. Increasing your intake of protein-rich foods like meat can be an easy way to help regulate your appetite. Breakfast may be the most important meal to load up on the protein. |

Ich werde mich der Kommentare enthalten.

Man muss vom Optimisten sein.

Sie haben solche unvergleichliche Phrase schnell erdacht?