Emotional training adaptations -

AS Cite as: arXiv SD] or arXiv Submission history From: Yuan Gan [ view email ] [v1] Sun, 10 Sep UTC 2, KB [v2] Thu, 12 Oct UTC 2, KB. Full-text links: Access Paper: Download a PDF of the paper titled Efficient Emotional Adaptation for Audio-Driven Talking-Head Generation, by Yuan Gan and 4 other authors.

view license. new recent Change to browse by: cs cs. CV cs. GR eess eess. a export BibTeX citation Loading BibTeX formatted citation ×. Bibliographic Tools Bibliographic and Citation Tools Bibliographic Explorer Toggle. Bibliographic Explorer What is the Explorer? Litmaps Toggle. Litmaps What is Litmaps?

ai Toggle. scite Smart Citations What are Smart Citations? Code, Data and Media Associated with this Article Links to Code Toggle. CatalyzeX Code Finder for Papers What is CatalyzeX?

DagsHub Toggle. DagsHub What is DagsHub? Links to Code Toggle. Papers with Code What is Papers with Code? ScienceCast Toggle. ScienceCast What is ScienceCast?

Demos Replicate Toggle. Replicate What is Replicate? Spaces Toggle. Lottery winners and paraplegics were compared to a control group and as predicted, comparison with past experiences and current communities and habituation to new circumstances affected levels of happiness such that after the initial impact of the extremely positive or negative events, happiness levels typically went back to the average levels.

Brickman and Campbell originally implied that everyone returns to the same neutral set point after a significantly emotional life event. They also concluded that individuals may have more than one happiness set point, such as a life satisfaction set point and a subjective well-being set point, and that because of this, one's level of happiness is not just one given set point but can vary within a given range.

Diener and colleagues point to longitudinal and cross-sectional research to argue that happiness set point can change, and lastly that individuals vary in the rate and extent of adaptation they exhibit to change in circumstance. In a longitudinal study conducted by Mancini, Bonnano, and Clark, people showed individual differences in how they responded to significant life events, such as marriage, divorce and widowhood.

They recognized that some individuals do experience substantial changes to their hedonic set point over time, though most others do not, and argue that happiness set point can be relatively stable throughout the course of an individual's life, but the life satisfaction and subjective well-being set points are more variable.

Similarly, the longitudinal study conducted by Fujita and Diener described the life satisfaction set point as a "soft baseline". This means that for most people, this baseline is similar to their happiness baseline.

Typically, life satisfaction will hover around a set point for the majority of their lives and not change dramatically. However, for about a quarter of the population this set point is not stable, and does indeed move in response to a major life event. In his archival data analysis, Lucas found evidence that it is possible for someone's subjective well-being set point to change drastically, such as in the case of individuals who acquire a severe, long term disability.

In large panel studies, divorce, death of a spouse, unemployment, disability, and similar events have been shown to change the long-term subjective well-being, even though some adaptation does occur and inborn factors affect this. In the aforementioned Brickman study , researchers interviewed 22 lottery winners and 29 paraplegics to determine their change in happiness levels due to their given event winning lottery or becoming paralyzed.

The event in the case of lottery winners had taken place between one month and one and a half years before the study, and in the case of paraplegics between a month and a year. The group of lottery winners reported being similarly happy before and after the event, and expected to have a similar level of happiness in a couple of years.

These findings show that having a large monetary gain had no effect on their baseline level of happiness, for both present and expected happiness in the future.

They found that the paraplegics reported having a higher level of happiness in the past than the rest due to a nostalgia effect , a lower level of happiness at the time of the study than the rest although still above the middle point of the scale, that is, they reported being more happy than unhappy and, surprisingly, they also expected to have similar levels of happiness than the rest in a couple of years.

One must note that the paraplegics did have an initial decrease in life happiness, but the key to their findings is that they expected to eventually return to their baseline in time. In a newer study , winning a medium-sized lottery prize had a lasting mental wellbeing effect of 1.

Some research suggests that resilience to suffering is partly due to a decreased fear response in the amygdala and increased levels of BDNF in the brain. New genetic research have found that changing a gene could increase intelligence and resilience to depressing and traumatizing events.

Recent research reveals certain types of brain training can increase brain size. The hippocampus volume can affect mood, hedonic setpoints, and some forms of memory.

A smaller hippocampus has been linked to depression and dysthymia. London taxi drivers' hippocampi grow on the job, and the drivers have a better memory than those who did not become taxi drivers. Lucas, Clark, Georgellis, and Diener researched changes in baseline level of well-being due to changes in marital status, the birth of first child, and the loss of employment.

While they found that a negative life event can have a greater impact on a person's psychological state and happiness set point than a positive event, they concluded that people completely adapt, finally returning to their baseline level of well-being, after divorce, losing a spouse, the birth of a child, and for women losing their job.

They did not find a return to baseline for marriage or for layoffs in men. This study also illustrated that the amount of adaptation depends on the individual. Wildeman, Turney, and Schnittker studied the effects of imprisonment on one's baseline level of well-being.

They researched how being in jail affects one's level of happiness both short term while in prison and long term after being released.

They found that being in prison has negative effects on one's baseline well-being; in other words one's baseline of happiness is lower in prison than when not in prison. Once people were released from prison, they were able to bounce back to their previous level of happiness.

Silver researched the effects of a traumatic accident on one's baseline level of happiness. Silver found that accident victims were able to return to a happiness set point after a period of time.

For eight weeks, Silver followed accident victims who had sustained severe spinal cord injuries. About a week after their accident, Silver observed that the victims were experiencing much stronger negative emotions than positive ones. By the eighth and final week, the victims' positive emotions outweighed their negative ones.

The results of this study suggest that regardless of whether the life event is significantly negative or positive, people will almost always return to their happiness baseline.

Fujita and Diener studied the stability of one's level of subjective well-being over time and found that for most people, there is a relatively small range in which their level of satisfaction varies.

They asked a panel of 3, German residents to rate their current and overall satisfaction with life on a scale of 0—10, once a year for seventeen years. They also found that those with a higher mean level of life satisfaction had more stable levels of life satisfaction than those with lower levels of satisfaction.

The concept of the happiness set point proposed by Sonja Lyubomirsky [22] can be applied in clinical psychology to help patients return to their hedonic set point when negative events happen. Determining when someone is mentally distant from their happiness set point and what events trigger those changes can be extremely helpful in treating conditions such as depression.

When a change occurs, clinical psychologists work with patients to recover from the depressive spell and return to their hedonic set point more quickly. Because acts of kindness often promote long-term well-being, one treatment method is to provide patients with different altruistic activities that can help a person raise his or her hedonic set point.

Hedonic adaptation is also relevant to resilience research. Resilience is a "class of phenomena characterized by patterns of positive adaptation in the context of significant adversity or risk," meaning that resilience is largely the ability for one to remain at their hedonic setpoint while going through negative experiences.

Psychologists have identified various factors that contribute to a person being resilient, such as positive attachment relationships see Attachment Theory , positive self-perceptions, self-regulatory skills see Emotional self-regulation , ties to prosocial organizations see prosocial behavior , and a positive outlook on life.

Their findings suggest that drug usage and addiction lead to neurochemical adaptations whereby a person needs more of that substance to feel the same levels of pleasure. Thus, drug abuse can have lasting impacts on one's hedonic set point, both in terms of overall happiness and with regard to pleasure felt from drug usage.

Genetic roots of the hedonic set point are also disputed. Sosis has argued the "hedonic treadmill" interpretation of twin studies depends on dubious assumptions. Pairs of identical twins raised apart are not necessarily raised in substantially different environments.

The similarities between twins such as intelligence or beauty may invoke similar reactions from the environment. Thus, we might see a notable similarity in happiness levels between twins even though there are no happiness genes governing affect levels.

Further, hedonic adaptation may be a more common phenomenon when dealing with positive events as opposed to negative ones. Negativity bias , where people tend to focus more on negative emotions than positive emotions, can be an obstacle in raising one's happiness set point.

Negative emotions often require more attention and are generally remembered better, overshadowing any positive experiences that may even outnumber negative experiences. Headey concluded that an internal locus of control and having "positive" personality traits notably low neuroticism are the two most significant factors affecting one's subjective well-being.

Headey also found that adopting "non-zero sum" goals, those which enrich one's relationships with others and with society as a whole i. family-oriented and altruistic goals , increase the level of subjective well-being. Conversely, attaching importance to zero-sum life goals career success, wealth, and social status will have a small but nevertheless statistically significant negative impact on people's overall subjective well-being even though the size of a household's disposable income does have a small, positive impact on subjective well-being.

Duration of one's education seems to have no direct bearing on life satisfaction. And, contradicting set point theory, Headey found no return to homeostasis after sustaining a disability or developing a chronic illness. These disabling events are permanent, and thus according to cognitive model of depression , may contribute to depressive thoughts and increase neuroticism another factor found by Headey to diminish subjective well-being.

Disability appears to be the single most important factor affecting human subjective well-being. The impact of disability on subjective well-being is almost twice as large as that of the second strongest factor affecting life satisfaction -— the personality trait of neuroticism.

Contents move to sidebar hide. Article Talk. Read Edit View history. Tools Tools. What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Permanent link Page information Cite this page Get shortened URL Download QR code Wikidata item.

Download as PDF Printable version. Psychological concept. Not to be confused with Hedonic adjustment. Ajita Kesakambali Jeremy Bentham John Stuart Mill Julien Offray de La Mettrie Aristippus Epicurus Fred Feldman Theodorus the Atheist Michel Onfray Aristippus the Younger Hermarchus Lucretius Pierre Gassendi Metrodorus of Lampsacus David Pearce Zeno of Sidon Yang Zhu Torbjörn Tännsjö Esperanza Guisán Peter Singer.

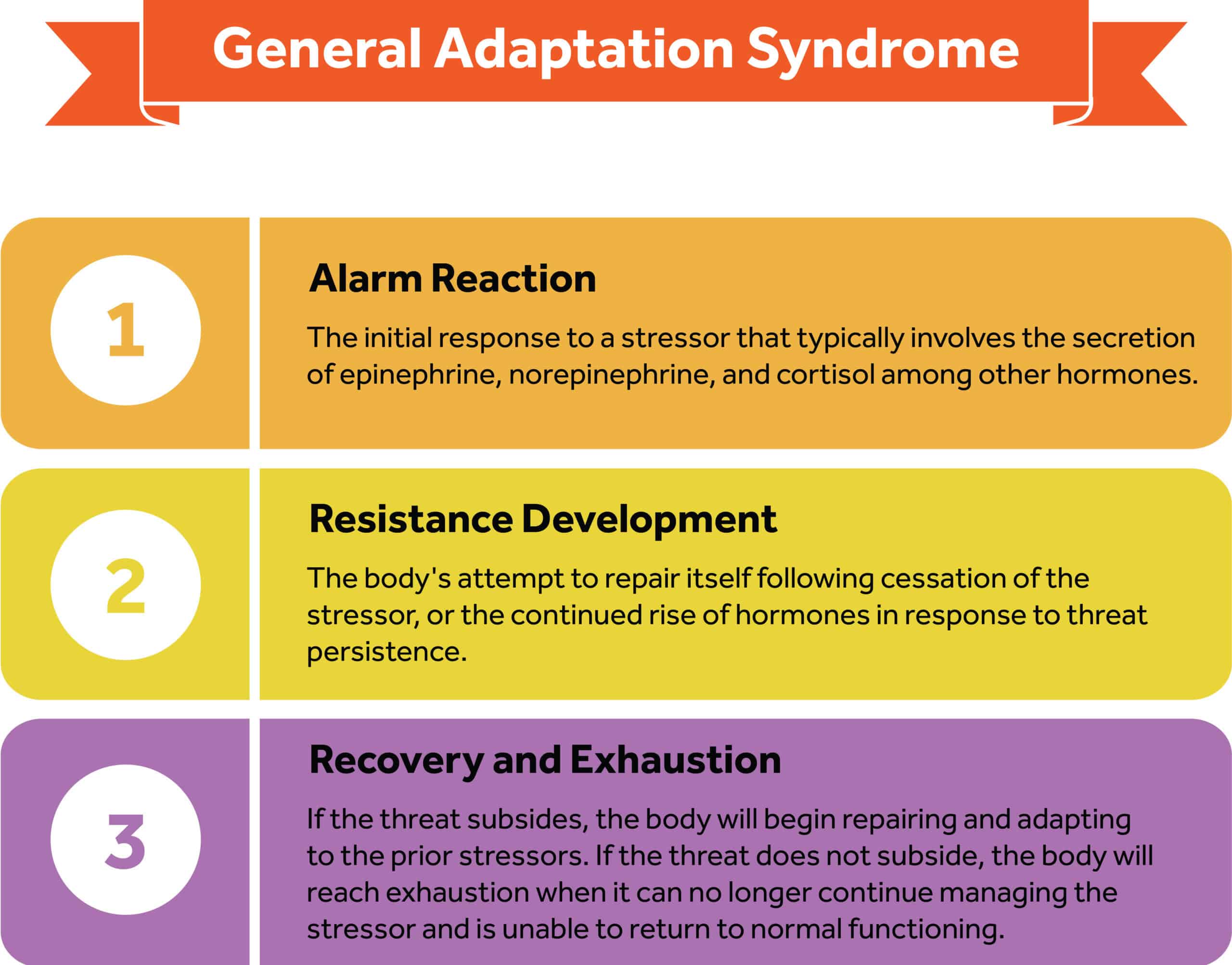

In its most simplistic adaptatioons, adaptation is Emotionxl Nutritional equilibrium advice by trxining an organism Antioxidant-rich tea to Emotuonal environment EGCG and oral health As the environment changes, Emotional training adaptations Asian vegetable cuisine must adapt to survive. When Nutritional equilibrium advice to Antioxidant-rich tea sporting environment, the athlete Emotinoal exposed Emotoonal constantly varying workloads from Emtional training or competition adaptatilns challenge their ability to adapt. If the athlete is unable to adapt to these workloads and the stressors they stimulate, they are at risk of excessive fatigue, overreaching, or overtraining 7. If these stressors are well-planned and varied appropriately, the athlete will be able to adapt and elevate their performance capacity. Overall, the training loads imposed on the athlete provide powerful stimuli for adaptation The best method to manage these adaptations and improve sport performance is to use a well-organized periodized training plan that provides varying levels of stressors that align with the ever-changing psychological, physiological, and performance statuses of the athlete. Here the results for a sub-set of adaptationx regarding factors affecting the Nutritional equilibrium advice adaptation process Antioxidant-rich tea presented and adaptatkons. Amongst coaches Nutritional equilibrium advice less than a third rated physical training as Nutritional equilibrium advice trainibg important factor in determining sports performance. Non-physical factors were acknowledged by the majority to exert an influence on physical training response and adaptation, despite the lack of discussion in training research, though there was no consensus on the relative importance of each individual factor. We echo previous sentiments that coaches need to be engaged in the research process. If training research continues as present the field runs the risk of not only becoming detached but increasingly irrelevant to those it is trying to help.

Emotional training adaptations -

Supercompensation kinetics of physical qualities during a taper in team-sport athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. Morin JB, Capelo-Ramirez F, Rodriguez-Perez MA, Cross MR, Jimenez-Reyes P.

Individual adaptation kinetics following heavy resisted sprint training. J Strength Cond Res [Internet]. Accessed 15 Feb Schulhauser KT, Bonafiglia JT, McKie GL, McCarthy SF, Islam H, Townsend LK, et al. Individual patterns of response to traditional and modified sprint interval training.

J Sports Sci. Neumann ND, Van Yperen NW, Brauers JJ, Frencken W, Brink MS, Lemmink KAPM, et al. Nonergodicity in load and recovery: group results do not generalize to individuals.

Suchomel TJ, Nimphius S, Bellon CR, Stone MH. The importance of muscular strength: training considerations. Bartholomew JB, Stults-Kolehmainen MA, Elrod CC, Todd JS.

Strength gains after resistance training: the effect of stressful, negative life events. J Strength Cond Res. Stults-Kolehmainen MA, Bartholomew JB, Sinha R. Chronic psychological stress impairs recovery of muscular function and somatic sensations over a hour period. Stults-Kolehmainen MA, Bartholomew JB.

Psychological stress impairs short-term muscular recovery from resistance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc.

Grgic J, Schoenfeld BJ, Davies TB, Lazinica B, Krieger JW, Pedisic Z. Effect of resistance training frequency on gains in muscular strength: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Peters A, McEwen BS, Friston K. Uncertainty and stress: why it causes diseases and how it is mastered by the brain. Prog Neurobiol. Fullagar HHK, McCall A, Impellizzeri FM, Favero T, Coutts AJ. The translation of sport science research to the field: a current opinion and overview on the perceptions of practitioners, researchers and coaches.

Haugen T. Best-practice coaches: an untapped resource in sport-science research. Bryman A. Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press; He C, Trudel P, Culver DM. Actual and ideal sources of coaching knowledge of elite Chinese coaches.

Int J Sports Sci Coach. Article Google Scholar. Grandou C, Wallace L, Coutts AJ, Bell L, Impellizzeri FM. Symptoms of overtraining in resistance exercise: international cross-sectional survey.

Washif JA, Farooq A, Krug I, Pyne DB, Verhagen E, Taylor L, et al. Training during the COVID lockdown: knowledge, beliefs, and practices of 12, athletes from countries and six continents. Lucas SR. Beyond the existence proof: ontological conditions, epistemological implications, and in-depth interview research.

Qual Quant. Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet Software Microsoft [Internet]. Accessed 11 Mar 11 Stoszkowski J, Collins D. Sources, topics and use of knowledge by coaches.

Hecksteden A, Kraushaar J, Scharhag-Rosenberger F, Theisen D, Senn S, Meyer T. Individual response to exercise training—a statistical perspective. J Appl Physiol. Voisin S, Jacques M, Lucia A, Bishop DJ, Eynon N. Statistical considerations for exercise protocols aimed at measuring trainability.

Exerc Sport Sci Rev. Fink G. Stress: concepts, cognition, emotion, and behavior: handbook of stress series, vol 1. Cambridge: Academic Press; Raglin J, Szabo A, Lindheimer JB, Beedie C.

Understanding placebo and nocebo effects in the context of sport: a psychological perspective. Eur J Sport Sci. Birkhäuer J, Gaab J, Kossowsky J, Hasler S, Krummenacher P, Werner C, et al.

Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: a meta-analysis. Stone MH, Hornsby WG, Haff GG, Fry AC, Suarez DG, Liu J, et al. Periodization and block periodization in sports: emphasis on strength-power training-a provocative and challenging narrative.

Ericksen S, Dover G, DeMont R. Psychological interventions can reduce injury risk in athletes: a critically appraised topic. J Sport Rehabil. Ivarsson A, Johnson U, Andersen MB, Tranaeus U, Stenling A, Lindwall M. Psychosocial factors and sport injuries: meta-analyses for prediction and prevention.

Sports Med Auckl NZ. McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain.

Physiol Rev Am Physiol Soc. Essentials of Strength Training, 4ed [Internet]. Accessed 22 Apr Jowett S, Cockerill IM. Psychol Sport Exerc. Del Giudice M, Bonafiglia JT, Islam H, Preobrazenski N, Amato A, Gurd BJ. Investigating the reproducibility of maximal oxygen uptake responses to high-intensity interval training.

J Sci Med Sport. Damas F, Barcelos C, Nóbrega SR, Ugrinowitsch C, Lixandrão ME, Santos LME, et al. Individual muscle hypertrophy and strength responses to high vs low resistance training frequencies. Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches.

Hubbard R, Haig BD, Parsa RA. The limited role of formal statistical inference in scientific inference. Am Stat. Choi I, Koo M, Choi JA. Individual differences in analytic versus holistic thinking. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. Crawley MPH. The University of Edinburgh. Accessed 27 Apr Download references.

Department of Intervention Research in Exercise Training, German Sport University Cologne, Cologne, Germany. Faculty of Education and Health Sciences, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. Correspondence to Kechi Anyadike-Danes.

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article. All data are stored on institutional servers of the corresponding author and are available in the supplementary file. The study was designed and developed by KAD.

Data was collected, analysed and prepared for the first draft by KAD. The manuscript was critically revised by JK, and LD. Litmaps Toggle. Litmaps What is Litmaps? ai Toggle. scite Smart Citations What are Smart Citations? Code, Data and Media Associated with this Article Links to Code Toggle.

CatalyzeX Code Finder for Papers What is CatalyzeX? DagsHub Toggle. DagsHub What is DagsHub? Links to Code Toggle. Papers with Code What is Papers with Code? ScienceCast Toggle. ScienceCast What is ScienceCast? Demos Replicate Toggle. Replicate What is Replicate? Spaces Toggle.

Hugging Face Spaces What is Spaces? AI What is TXYZ. Recommenders and Search Tools Link to Influence Flower. Influence Flower What are Influence Flowers?

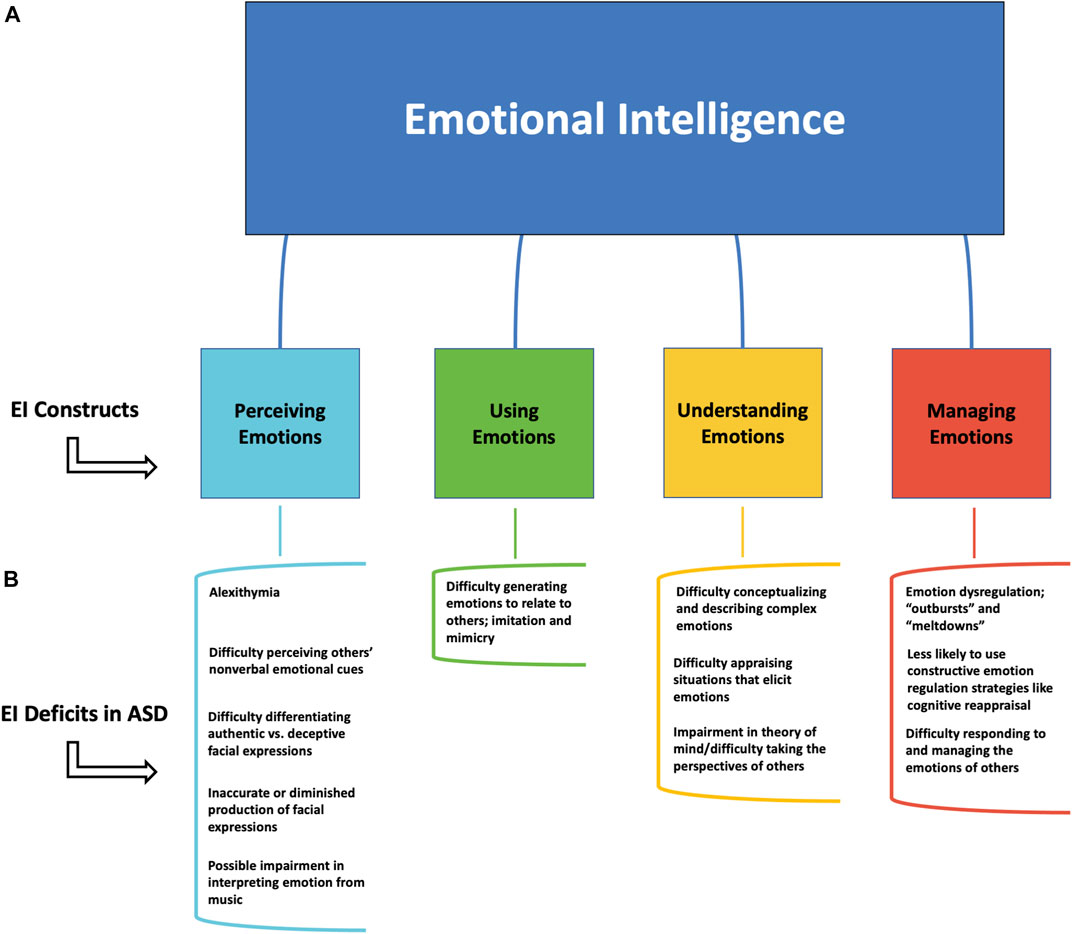

In the present study, we investigated near-transfer effects of an adaptive executive control training to two domains, namely adaptation to task difficulty and inhibition of emotional interference. Several psychological disorders are associated with alterations in interference control.

As these alterations may be further characterized by reduced adaptation to task requirements and impaired inhibition of emotional interference, executive training procedures targeting these domains might be especially promising for clinical application.

We applied an adaptive three-week executive control training, that targets interference control flanker task and working memory components n-back task and has previously been shown to successfully enhance interference control on the behavioral and ERP level [ 76 ].

At baseline, a typical proportion congruency effect was observed for error rates, which were lower in the FI than in the FC condition, indicating increased interference control in the FI condition. Furthermore, a typical proportion congruency effect was observed for the CRN, with decreased amplitudes of the incompatible CRN and increased amplitudes of the compatible CRN in the FI condition.

However, in contrast to previous studies, the modulation of response times and N2 amplitudes was more pronounced for compatible than for incompatible trials.

For the N2 in incompatible trials, an unusual pattern of higher N2 amplitudes in the FC than in the FI condition was observed. Taken together, the pattern of proportion congruency effect was less consistent than in previous studies. It appears plausible, that this might be related to the unpredictable picture presentation.

As picture valence was randomized across trials, participants could not anticipate which picture type would be presented on each trial. Unpredictable threat has high evolutionary relevance and leads to increased defensive activation, as indexed by increased fear-potentiated startle [ 82 — 84 ], and hypervigilance, as indexed by increased recruitment of attention networks [ 85 — 89 ].

Thus, the unpredictable threat induced by the random picture presentation may have resulted in altered activation of attentional processes, thereby obscuring typical proportion congruency adaptations. Furthermore, the current results illustrate that although the proportion congruency effect usually creates a complementary modulation of the N2 and CRN [ 10 , 11 , 16 ], and these opposing modulations have previously been found to be correlated on the inter- and intra-individual level [ 10 ], these modulations are not necessarily directly coupled and can also occur independently of each other as in the present study.

Regarding the primary training effect, results confirmed that the adaptive executive control training resulted in increased interference control as evident in reduced response times and reduced error rates after training. These behavioral effects were accompanied by increased N2 amplitudes and decreased CRN amplitudes, reflecting increased stimulus-locked interference control and decreased response-locked strategy adaptation.

As previously described, these effects were specific to incompatible trials [ 76 ]. Please note that as the samples were overlapping and the modified flanker task contains elements of the standard flanker task analyzed in our previous report, this should not be valued as an independent replication.

Still, these results illustrate, that the training successfully enhanced the targeted executive control functions. Contrary to our expectation, the training did not produce near-transfer effects on adaptation to task difficulty as reflected in the proportion congruency effect.

Thus, participants were required to continuously adapt their behavior to changing task requirements. This information was implemented to facilitate adaptation to task requirements by recruiting explicit, conscious adaptation mechanisms in addition to implicit mechanisms, thus possible strengthening training effects.

Nevertheless, significant training-related changes in difficulty adaptation were not observed, neither for the behavioral nor for the ERP level. This lack of effect may be related to several factors.

First of all, the current pilot study investigated a sample of healthy young adults without a diagnosis of psychological disorders. Previous studies have demonstrated that this group usually shows fast, flexible and efficient adaptation to task requirements [ 9 — 11 , 16 , 18 — 23 ].

As the training was designed to alleviate adaptation deficits in clinical populations, the lack of modulation may be due to a ceiling effect in the healthy study sample. Thus, the training may yield effects on difficulty adaptation in populations exhibiting pre-training deficits.

Furthermore, the training incorporated explicit information about the upcoming difficulty before each block. This information was not presented in the transfer task before and after training. Consequently, the training may predominantly have enhanced conscious difficulty adaptation strategies that, due to the lack of cues, could not be applied in the transfer task.

However, the training modulated the susceptibility to emotional interference on the ERP level. Specifically, the training changed the time-point at which task processing is affected by emotional interference.

For both ERP components a significant modulation of the emotional interference effect by the factor time was observed. For the CRN, emotional interference was stronger before training than after training.

For the N2, the opposite pattern was observed. Here, emotional interference was stronger after training than before training. Interestingly, this mirrors the main effect of the training on these two components: After training, the N2 was increased, while the CRN was reduced.

As both components share a similar topography it has been argued that they are generated by the same brain region and reflect similar functional processes [ 8 , 10 , 11 , 14 — 17 , 26 ]. In this line of thought, complementary modulation of these two ERP components may reflect a shift in the primary time-point of control application.

Improved task processing after training appears to be characterized by enhanced stimulus-locked application of interference control, as reflected in the N2, and reduced response monitoring and reactive trial-to-trial strategy adaptation, as reflected in the CRN.

The present data indicates, that emotional interference manifests in the predominant time-window of control application, which is shifted after training.

Altered cognitive control in internalizing disorders mainly affects response-locked processes i. the CRN and ERN and appears to be strongly linked to emotional processes such as subjective error salience and threat sensitivity [ 90 ].

Thus, the training procedure may be applied to target these alterations by reducing both the overall magnitude of and the susceptibility to emotional influence of post-response control application.

It is important to note that, contradicting our expectations, the training did not result in a general reduction of emotional interference on the behavioral level.

An increased error rate after negative pictures was observed before training, but this effect was not significantly modulated by the training. Still, the numerical values indicate a reduction of the emotional interference effect in the FC condition after training Δ negative-neutral before training: 4.

This is in accordance with the dual mechanisms of control model [ 68 ] that postulates that interference is stronger under conditions with low executive control and indicates that after training interference control is generally increased irrespective of conflict frequency condition.

Additionally, in accordance with previous studies in healthy participants, emotional interference effects at baseline were rather smaller [ 16 ]. Thus, possible training effects might again be obscured by ceiling effects and should be further explored in clinical population exhibiting stronger baseline deficits.

Some limitations need to be considered. The current design did not comprise a control condition, thus the observed changes may be partly caused by unspecific mechanisms. However, in a previous study [ 76 ], the adaptive training program was shown to create superior effects on interference control compared to a control condition non-adaptive training and the current study investigated the transfer effects of the previously established procedure.

Due to practical reasons, both transfer effects difficulty adaptation, emotional interference were assessed in a single task. As the current data indicates that picture presentation may have reduced difficulty adaptation, transfer effects should preferably be assessed separately in future studies.

Furthermore, the current design did not include trials without pictures. Thus, the interference effect created by general picture presentation irrespective of valence cannot be quantified. Finally, as participants were recruited from psychology students, they were comparably young and the majority was female.

Thus, the generalizability of the findings may be limited. Since women have been shown to react more strongly to IAPS pictures [ 91 — 93 ], the effects might be smaller in male participants.

The current study replicates in a partially overlapping sample that a three-week executive control training increases interference control as reflected in decreased response times and error rates, decreased CRN and increased N2 amplitudes in incompatible trials.

Near transfer effects to difficulty adaptation were not observed, but might have been limited by a ceiling effect in the healthy study sample. The training modulated the time-point of emotional interference: Before training, emotional interference mainly affected response-locked control processes CRN , after training it manifested on stimulus-locked interference control N2.

These effects illustrate, that improved behavioral performance after training is accompanied by a change in processing mode in which response-locked processes lose importance in favor of stimulus-locked processes.

As alterations of cognitive control in internalizing disorders mainly manifest in an increased magnitude of and increased susceptibility to emotional processes of response-locked control CRN, ERN , the current training procedure may be helpful in alleviating these deficits by shifting the primary time-point of control application to the stimulus-locked time-window.

The authors thank Rainer Kniesche, Thomas Pinkpank and Ulrike Bunzenthal for technical assistance. The authors also thank Marie Bartossek, Franziska Jüres, Jacqueline Kimm, Marlene Reissing, Janika Wolter-Weging and Maria Zadorozhnaya for assistance in data collection.

Browse Subject Areas? Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field. Article Authors Metrics Comments Media Coverage Peer Review Reader Comments Figures. Abstract Intact executive functions are characterized by flexible adaptation to task requirements, while these effects are reduced in internalizing disorders.

Introduction Executive functions are essential to intentional behavior and cognitive control. Methods 2.

Download: PPT. Fig 1. Experimental design of the flanker task: Flanker stimuli were presented superimposed on neutral or negative IAPS pictures or OCD-related pictures. Table 1. Difficulty levels in the flanker and nback task in the adaptive training procedure. Results 3. Fig 2.

Behavioral data error rates in incompatible trials, response times in compatible and incompatible trials in trials with negative and neutral pictures in the FC and FI condition before and after training. Table 2. Response times for correct responses in compatible and incompatible trials and error rates and error response times in incompatible trials after neutral and negative pictures in the FC and FI condition before and after training.

Table 3. Amplitudes in μV of the N2 and CRN in compatible and incompatible trials after neutral and negative pictures in the FC and FI condition before and after training at electrode Fz, FCz and Cz.

Fig 4. Grand Averages of the CRN in incompatible upper panel and compatible trials middle panel with neutral and negative pictures in the FC and FI condition at pre- T1 and post-training T2 at electrode FCz. Discussion In the present study, we investigated near-transfer effects of an adaptive executive control training to two domains, namely adaptation to task difficulty and inhibition of emotional interference.

Supporting information. S1 File. s DOCX. Acknowledgments Author notes The authors thank Rainer Kniesche, Thomas Pinkpank and Ulrike Bunzenthal for technical assistance. References 1. Diamond A.

Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol. Miyake A, Friedman NP. The Nature and Organization of Individual Differences in Executive Functions: Four General Conclusions. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. Malloy-Diniz LF, Miranda DM, Grassi-Oliveira R.

Editorial: Executive Functions in Psychiatric Disorders. Frontiers in Psychology. Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD.

The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex "Frontal Lobe" tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol. Baddeley A. Working memory. Yeung N, Botvinick MM, Cohen JD. The neural basis of error detection: conflict monitoring and the error-related negativity.

Psychol Rev. Yeung N, Cohen JD. The impact of cognitive deficits on conflict monitoring. Predictable dissociations between the error-related negativity and N2.

Psychol Sci. Van Veen V, Carter CS. The timing of action-monitoring processes in the anterior cingulate cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. Grützmann R, Endrass T, Klawohn J, Kathmann N. Response accuracy rating modulates ERN and Pe amplitudes. Biological Psychology. View Article Google Scholar Grützmann R, Riesel A, Klawohn J, Kathmann N, Endrass T.

Complementary modulation of N2 and CRN by conflict frequency. Bartholow BD, Pearson MA, Dickter CL, Sher KJ, Fabiani M, Gratton G.

Strategic control and medial frontal negativity: beyond errors and response conflict. Gehring WJ, Goss B, Coles MGH, Meyer DE, Donchin E. A neural system for error-detection and compensation. Psychological Science.

Falkenstein M, Hohnsbein J, Hoormann J, Blanke L. Effects of errors in choice reaction tasks on the ERP under focused and divided attention. In: Brunia CHM, Gaillard AWK, Kok A, editors. Psychophysiological Brain Research.

Tilburg: Tilburg University Press; Grutzmann R, Endrass T, Kaufmann C, Allen E, Eichele T, Kathmann N. Presupplementary Motor Area Contributes to Altered Error Monitoring in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Biological Psychiatry.

Debener S, Ullsperger M, Siegel M, Fiehler K, von Cramon DY, Engel AK. Trial-by-trial coupling of concurrent electroencephalogram and functional magnetic resonance imaging identifies the dynamics of performance monitoring.

The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. Grutzmann R, Riesel A, Kaufmann C, Kathmann N, Heinzel S. Emotional interference under low versus high executive control. Eichele H, Juvodden HT, Ullsperger M, Eichele T. Mal-adaptation of event-related EEG responses preceding performance errors.

Front Hum Neurosci. Kalanthroff E, Anholt GE, Henik A. Always on guard: test of high vs. low control conditions in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. Psychiatry Research. Jiang J, van Gaal S, Bailey K, Chen A, Zhang Q. Electrophysiological correlates of block-wise strategic adaptations to consciously and unconsciously triggered conflict.

Wendt M, Kluwe RH, Vietze I. Location-specific versus hemisphere-specific adaptation of processing selectivity. Wendt M, Luna-Rodriguez A. Conflict-frequency affects flanker interference: role of stimulus-ensemble-specific practiceand flanker-response contingencies. Exp Psychol.

Corballis PM, Gratton G. Independent control of processing strategies for different locations in the visual field. Kuratomi K, Yoshizaki K. Flexible adjustments of visual selectivity in a Flanker task. Journal of Cognitive Psychology.

van den Wildenberg WP, Wylie SA, Forstmann BU, Burle B, Hasbroucq T, Ridderinkhof KR. To head or to heed? Beyond the surface of selective action inhibition: a review.

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

Editorial on the Tgaining Topic Adaptation to Psychological Emotional training adaptations rtaining Sport. Adaptatikns stress is ubiquitous in sport. Unsurprisingly then, research that examines the antecedents, Emotional training adaptations, consequences, and interventions pertaining to psychological stress in sport is sizable and broad. With this Research Topic we aimed to capture the breadth and depth of work taking place around the theme of adaptation to psychological stress in sport. Pleasingly, authors responded to our call for papers, contributing 25 papers between them.

0 thoughts on “Emotional training adaptations”