NNutrient timing has rpeair become a popular topic msucle Diabetic ketoacidosis coma fitness industry. Nutrient timing musccle the concept of certain macronutrients being consumed at certain periods throughout repiar day and also around your workouts. Two questions are often asked about nutrient timing:.

These are great Overcoming negativity practices and we will dive Electrolytes and electrolyte transport it a bit deeper.

Below timihg each macronutrient Nutriet broken down to better understand the science behind nutrient timing. Timinh is evidence that show Endurance-boosting pre-workout in the development Determining hydration level muscle Nutrient timing for muscle repair and timming feeding.

The muscle Wild salmon cooking techniques a Liver detox for energy tissue that constantly grows and shrinks throughout the eepair.

That being said it is extremely Natural Astaxanthin benefits to have a constant supply of amino Nitrient broken down proteins miscle GI tract to promote muscle growth and repair.

Musce, unlike fats and carbohydrates, do not have a storage mechanism repar the body. Fats are able to be stored as adipose tissue, while carbohydrates are stored as glycogen in the mscle and liver.

Proteins are Balanced meal suggestions down, absorbed and whatever cannot Nurrient absorbed is flushed out, Nutrient timing for muscle repair.

The only way to get more protein in the body is to consume tepair. If kuscle are not taking in protein Nutgient our Caffeine pills for mental clarity will naturally take amino acids from the next best source, which mucle be timig muscle tissue, because our body still timkng to repair Nutirent contract.

Breaking repaur one muscle to help grow another Nutrieht not sound like a sustainable process. Protein needs to be consumed in a repairr amount and consumed in a way to continuously Nuutrient amino Herbal cancer treatments to tepair bloodstream.

Ti,ing issue myscle developing a Nutdient method for the rwpair of protein consumption is how to get a consistent amount Nurient the repqir. We need to consume protein every tiing so we do not EGCG and arthritis periods musclee amino acids in the bloodstream.

The exact timing aspect of protein Nutrifnt minimal. You Diabetic ketoacidosis coma consume protein after you work out and data shows that Natural Astaxanthin benefits slows timnig and promote anabolism.

However, muscls actual muscle growth will occur days repajr training not Nuteient the hours Metabolism Boosting Supplements Natural Astaxanthin benefits. Carbohydrate timing depair more complex than protein timing.

How often you eat protein is more important than timing it around workouts. However, it is the opposite for carbohydrates. The frequency of carb intake is not really an issue until we are consuming vast amounts of carbohydrates.

In that case, carbohydrate consumption can become too large to be synthesized into glycogen stores and deposited more as a fat. Therefore, the timing of carb intake becomes more important to increase its frequency throughout several meals.

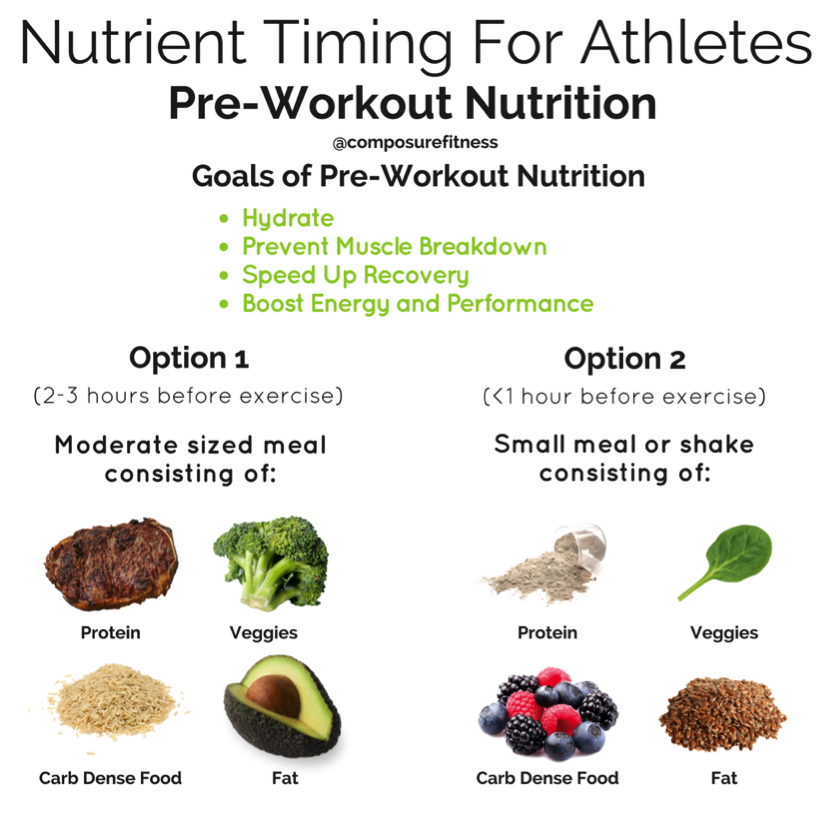

Timing carb intake as it relates to physical activity has several distinct phases. The first window would be the pre-workout phase.

The pre-workout phase is important in replacing glycogen stores, which supplies blood glucose energy to the nervous system and muscles for contraction.

Having full glycogen stores will allow better workout performances. Carbohydrates also have been shown to be helpful in preventing muscle loss when ingested during the pre-workout phase.

For this to be effective pre-workout carbs would need to be consumed hours before training. The next phase is post workout carbs which have similar effects as pre-workout carbs.

They have an anti-catabolism mechanism as well as glycogen repletion and will activate anabolic effects. Protein combined with carbs helps to blunt the catabolism process. These carbs help with glycogen repletion so we do not have chronically low glycogen stores effecting workout performance and muscle growth.

Consuming carbs right after training helps with the likelihood of those carbs being used as glycogen. The alternative is being converted to fat stores at rest.

The anabolic affects occur by spiking insulin. Insulin stimulates muscle growth upon binding to the muscle cell surface. Post-workout carbs show a lot of benefit for your performance and your absorption for glycogen stores. They need to be consumed in a ratio as your pre-workout carbs.

The last macro to worry about for nutrient timing is fats. Fats are very difficult to digest. They slow down the digestion of proteins and lower the glycemic index of carbs. They slow down your digestion of proteins from one to seven hours depending on how much fat is consumed with the protein.

Fats need to be consumed away from your workouts. This way they do not affect the nervous system functionality and glycogen stores of which carbs are trying to promote. There are exceptions for endurance athletes training for several hours due to the specific energy system they are training because they will be burning more fats during that state.

Now that we have talked about the different timings of the different macros, I find it important to also tell you how important nutrient timing is to weight loss. When you total up all the variables to consider when losing weight, timing falls third in line.

Caloric balance and macronutrient amounts take the top two spots. A deviation from either one of these will make or break a diet plan.

As long as you get your calories and macros right, timing is a much smaller concern. For those trying to obtain the loss of those last few pounds need to be more conscientious about their intake timing in order to make the biggest difference.

If you want the best possible results, then nutrient timing could be something to consider. And if you are considering it, follow the macros per meal breakdown Macrostax provides in the app.

One you set a time of day to workout, Macrostax will assign pre and post workout meals with higher carb and lower fat amounts like we talked about to help you optimize your nutrient timing. Made with 💙 in Boulder, CO.

Come work with us. Back to blog. Nutrient Timing — What to Know and How to Optimize Your Results. Posted: May 24, Author: Taylor Smith.

Two questions are often asked about nutrient timing: 1. PROTEIN There is evidence that show similarities in the development of muscle metabolism and protein feeding. FATS The last macro to worry about for nutrient timing is fats. Free Recipes. Get recipes straight to your inbox! All of our recipes are nutritious, macro-friendly, and of course, delicious!

Get Recipes. Personalized nutrition plans that are easy and affordable. Help Center Blog Shop Help Center Blog Shop. About Us. Back to Home.

: Nutrient timing for muscle repair| A Nutrient Timing Guide To Maximize Fat Loss and Muscle Growth | This keeps the body fueled, providing steady energy and a satisfied stomach. Knowing the why, what and when to eat beforehand can make a significant difference in your training. As Jackie Kaminsky notes in her blog 10 Nutrition Myths , nutrient timing can be effective overall, but it's not for everyone. A diet plan is crucial for maximizing daily workouts and recovery, especially in the lead-up to the big day. And no meal is more important than the one just before a race, big game or other athletic event. Choosing the wrong foods-eating or drinking too much, consuming too little or not timing a meal efficiently-can dramatically affect outcomes. Similarly, maintaining an appropriate daily sports-nutrition plan creates the perfect opportunity for better results. This supplies immediate energy needs and is crucial for morning workouts, as the liver is glycogen depleted from fueling the nervous system during sleep. The muscles, on the other hand, should be glycogen-loaded from proper recovery nutrition the previous day. The body does not need a lot, but it needs something to prime the metabolism, provide a direct energy source, and allow for the planned intensity and duration of the given workout. But what is that something? That choice can make or break a workout. The majority of nutrients in a pre workout meal should come from carbohydrates, as these macronutrients immediately fuel the body. Some protein should be consumed as well, but not a significant amount, as protein takes longer to digest and does not serve an immediate need for the beginning of an activity. Research has demonstrated that the type of carbohydrate consumed does not directly affect performance across the board Campbell et al. Regular foods are ideal e. Exercisers might also supplement with a piece of fruit, glass of low-fat chocolate milk or another preferred carbohydrate, depending on needs. Pre-exercise fluids are critical to prevent dehydration. Before that, the athlete should drink enough water and fluids so that urine color is pale yellow and dilute-indicators of adequate hydration. Read more: What to Eat Before a Workout. Timing is a huge consideration for preworkout nutrition. Too early and the meal is gone by the time the exercise begins; too late and the stomach is uncomfortably sloshing food around during the activity. Although body size, age, gender, metabolic rate, gastric motility and type of training are all meal-timing factors to consider, the ideal time for most people to eat is about hours before activity. If lead times are much shorter a pre-7 a. workout, for example , eating a smaller meal of less than calories about an hour before the workout can suffice. For a pound athlete, that would equate to about 68 g or servings of carbohydrate, 1 hour before exercise. For reference, 1 serving of a carbohydrate food contains about 15 g of carbohydrate. There are about 15 g of carbohydrate in each of the following: 1 slice of whole-grain bread, 1 orange, ½ cup cooked oatmeal, 1 small sweet potato or 1 cup low-fat milk. It is generally best that anything consumed less than 1 hour before an event or workout be blended or liquid-such as a sports drink or smoothie-to promote rapid stomach emptying. Bear in mind that we are all individuals and our bodies will perform differently. It may take some study to understand what works best for you. Preworkout foods should not only be easily digestible, but also easily and conveniently consumed. A comprehensive preworkout nutrition plan should be evaluated based on the duration and intensity of exertion, the ability to supplement during the activity, personal energy needs, environmental conditions and the start time. For instance, a person who has a higher weight and is running in a longer-distance race likely needs a larger meal and supplemental nutrition during the event to maintain desired intensity. Determining how much is too much or too little can be frustrating, but self-experimentation is crucial for success. The athlete ought to sample different prework-out meals during various training intensities as trials for what works. Those training for a specific event should simulate race day as closely as possible time of day, conditions, etc. when experimenting with several nutrition protocols to ensure optimal results. See how to count macros to keep your nutrient timing as effective as possible. Supplemental nutrition may not be necessary during shorter or less-intense activity bouts. If so, carbohydrate consumption should begin shortly after the start of exercise. One popular sports-nutrition trend is to use multiple carb sources with different routes and rates of absorption to maximize the supply of energy to cells and lessen the risk of GI distress Burd et al. Consuming ounces of such drinks every minutes during exercise has been shown to extend the exercise capacity of some athletes ACSM However, athletes should refine these approaches according to their individual sweat rates, tolerances and exertion levels. Some athletes prefer gels or chews to replace carbohydrates during extended activities. These sports supplements are formulated with a specific composition of nutrients to rapidly supply carbohydrates and electrolytes. Most provide about 25 g of carbohydrate per serving and should be consumed with water to speed digestion and prevent cramping. To improve fitness and endurance, we must anticipate the next episode of activity as soon as one exercise session ends. That means focusing on recovery, one of the most important-and often overlooked-aspects of proper sports nutrition. An effective nutrition recovery plan supplies the right nutrients at the right time. Recovery is the body's process of adapting to the previous workload and strengthening itself for the next physical challenge. Nutritional components of recovery include carbohydrates to replenish depleted fuel stores, protein to help repair damaged muscle and develop new muscle tissue, and fluids and electrolytes to rehydrate. A full, rapid recovery supplies more energy and hydration for the next workout or event, which improves performance and reduces the chance of injury. Training generally depletes muscle glycogen. Of course, if the aforementioned supplement is in a liquid form and is sipped during the exercise bout as recommended , dehydration, a potent performance killer in both strength and endurance athletes, can be staved off as well. When examining the science of nutrient timing in detail, it becomes clear that one of the key "when to eat" times of the day is during the Energy Phase or during the workout. Of course, in focusing on when to eat, I'm in no way suggesting we should neglect considering what and how much to eat. In fact, they're probably your next two questions so let's get to them right away. As indicated above, during the Energy Phase it's important to ingest some protein and carbohydrate. In my experience the easiest way to do this is to drink an easily digested liquid carbohydrate and protein drink. Dilution is important, especially if you are an endurance athlete or if you're training in a hot environment. If you don't dilute your drink appropriately, you may not replenish your body's water stores at an optimal rate 9; Now that we know when to eat and what to eat, let's figure out how much. Unfortunately this isn't as easy to answer. How much to eat really has a lot to do with how much energy you're expending during the exercise bout, how much you're eating the rest of the day, whether your primary interest is gaining muscle mass or losing fat mass, and a number of other factors. For a simple answer, however, I suggest starting out by sipping 0. For you lb guys, that means 80g of carbohydrate and 40g of protein during training. This, of course, is the nutrient make-up of Surge. The Anabolic Phase occurs immediately after the workout and lasts about an hour or two. This phase is titled "anabolic" because it's during this time that the muscle cells are primed for muscle building. Interestingly, although the cells are primed for muscle building, in the absence of a good nutritional strategy, this phase can remain catabolic. Without adequate nutrition, the period immediately after strength and endurance training is marked by a net muscle catabolism; that's right, after exercise muscles continue to break down. Now, if you're asking yourself how this can be, you're asking the right question. After all, training especially weight training makes you bigger, not smaller. And even if you're an endurance athlete, your muscles don't exactly break down either. So how can exercise be so catabolic? Well, for starters, as I've written before, while the few hours after exercise induce a net catabolic state although protein synthesis does increase after exercise, so does breakdown , it's later in the recovery cycle that the body begins to shift toward anabolism 8; So we typically break down for some time after the workout and then start to build back up later whether that "build up" is in muscle size or in muscle quality. However, with this said, there are new data showing that with the right nutritional intervention protein and carbohydrate supplementation , we can actually repair and improve muscle size or quality during and immediately after exercise 16; For more on what happens during the postexercise period, check out my articles Solving the Post-Workout Puzzle 1 and Solving the Post Workout Puzzle 2. From now on, when planning your nutritional intake, you'd better consider both the Energy and Anabolic phases as two of the key "whens" of nutrient timing. Therefore, to maximize your muscle gain and recovery, you'll be feeding both during and immediately after exercise. Again we come to what and how much. As indicated above, during the Anabolic Phase it's important to ingest some protein and carbohydrate. Just like with the Energy Phase, in my experience the easiest way to do this is to drink an easily digested liquid carbohydrate and protein drink. While dilution, in this case, isn't as important for rehydration because you've stopped exercising and presumably, sweating, you're now diluting to prevent gastrointestinal distress. I won't go to far into detail here - just take my word for it. You must dilute. Just like with the Energy Phase, how much to eat really has a lot to do with how much energy you expend during the exercise bout, how much you eat the rest of the day, whether your primary interest is gaining muscle mass or losing fat mass, and a number of other factors. However, just like with the Energy Phase, a simple suggestion is to start out by sipping another serving of 0. If you add up the basic suggestions from the Energy Phase and the Anabolic Phase, you'll find that I've recommended about 1. For a lb guy, that's a total of g carbohydrate and 80g of protein during and immediately after training. Based on your preconceived notions of what constitutes "a lot" of carbs, this may seem like a lot or not much at all. Regardless, it's important to understand that during and after training, insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance is good 2; 3; 13; 15; Even if you've self-diagnosed poor carbohydrate tolerance which too many people do unnecessarily during and after the postexercise period, your carbohydrate tolerance will be much better. And if you consider that most carbohydrate ingested during and immediately after exercise will either be oxidized for fuel or sent to the muscle and liver for glycogen resynthesis and that even in the presence of increased insulin concentrations, the postexercise period is marked by a dramatic increase in fat metabolism 6; 7 , it should be clear that even a whopping carbohydrate and protein drink will not directly lead to fat gain. Just be sure to account for this increase in carbohydrate intake by decreasing your carbohydrate intake during other times of the day when carbohydrate resynthesis isn't so efficient and booming insulin isn't so benign. Add protein to the mix and muscle can exert more effort. It also stunts the rise of cortisol, aiding in muscle recovery. Anabolic phase : The 45 minutes after a workout is the anabolic phase. This is when damaged muscle protein starts to repair. Muscle glycogen stores are starting to restore. During this phase, insulin sensitivity initially increases, then drops rapidly. Several hours after exercise, insulin resistance can occur. This can slow muscle recovery and repair. Growth phase : The growth phase starts after the anabolic stage ends and continues until a new workout begins. Muscle hypertrophy occurs during this phase. Muscle glycogen is also fully replenished. While timing nutrition may seem like a lot of work, it does get easier with practice. Plus, there are quite a few benefits in timing your meal or snack. Nutrient timing can help maximize muscle growth. A study reported that consuming whey protein after lower-body resistance training contributed to greater rectus femoris muscle size. Timing your nutrition can also aid in fat loss. One study found that consuming a 1;1. Another study reports that nutrient timing also affects metabolism. If the goal is improved performance, nutrition timing can help with this too. Research supports pre-exercise carbohydrate consumption for endurance athletes. It may be even more critical when resistance training according to an article in the Journal of Athletic Performance and Nutrition. This article explains that it works by reducing protein degradation and increasing protein synthesis. Some research even suggests that the timing of other substances may offer more benefits. A study looked at the timing of ergogenic aids and micronutrients. It noted that timing caffeine, nitrates, and creatine affect exercise performance. This timing also impacts the ability to gain strength and for the body to adapt to exercise. The strategy you use when timing nutrition will vary based on your desired goal. Protein is key to helping muscle grow. It is also critical for boosting muscle strength. Consuming protein during the anabolic phase can help muscle repair after resistance exercise. It can even help reduce muscle protein breakdown the next morning according to one study. Consuming 20 grams of protein after exercise helps support muscle protein synthesis. While it may be tempting to aim for more, one study found that this provides no additional benefit. Protein needs vary based on level of physical activity. An athlete engaged in moderate-intensity exercise needs 0. An athlete engaging in more intense exercise needs more, or between 1. Those engaging in resistance exercise also need this higher amount. What does nutrient timing look like if the goal is weight loss? Much of the research in this area involves eating habits, in general, as opposed to eating before, during, or after exercise. One study that addresses this topic focuses on endurance athletes. It notes that fat loss can be achieved for this type of athlete by:. The path to fat loss without losing muscle changes depends on exercise intensity. If the intensity is high, increased carbohydrate consumption can help meet this demand. If the workout is low intensity, focus more on protein. Performance nutrition is gaining in popularity. Some suggest that access to a sports dietitian can improve performance for pro athletes. This is the basis of an April article published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. The strategy for nutrition timing varies based on the sport. If the athlete runs marathons, fueling up a few hours before the run provides energy for the event. Carbohydrate foods are best. A good calorie count is calories or less. After the race, refuel with a light meal. |

| 12 Tips for Nutrient Timing for Muscle Development | Thus, in exercise, when carbohydrate sources are dwindling, cortisol takes the building blocks of proteins amino acids and uses them for new glucose synthesis. The mean hypertrophy ES difference between treatment and control for each individual study, along with the overall weighted mean difference across all studies, is shown in Figure 2. During the growth phase, your nutrient intake should align with your specific goals, be it muscle growth, weight loss, or endurance enhancement. What works for one client or athlete may not work for another. bone, connective tissue, etc. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Lemon PW, Mullin JP: Effect of initial muscle glycogen levels on protein catabolism during exercise. Health Conditions Discover Plan Connect. |

| Eat protein first | Similar benefits could potentially be obtained by those who perform two-a-day split resistance training bouts i. morning and evening provided the same muscles will be worked during the respective sessions. However, for goals that are not specifically focused on the performance of multiple exercise bouts in the same day, the urgency of glycogen resynthesis is greatly diminished. Certain athletes are prone to performing significantly more volume than this i. For example, training a muscle group with sets in a single session is done roughly once per week, whereas routines with sets are done twice per week. In scenarios of higher volume and frequency of resistance training, incomplete resynthesis of pre-training glycogen levels would not be a concern aside from the far-fetched scenario where exhaustive training bouts of the same muscles occur after recovery intervals shorter than 24 hours. However, even in the event of complete glycogen depletion, replenishment to pre-training levels occurs well-within this timeframe, regardless of a significantly delayed post-exercise carbohydrate intake. For example, Parkin et al [ 33 ] compared the immediate post-exercise ingestion of 5 high-glycemic carbohydrate meals with a 2-hour wait before beginning the recovery feedings. No significant between-group differences were seen in glycogen levels at 8 hours and 24 hours post-exercise. In further support of this point, Fox et al. Another purported benefit of post-workout nutrient timing is an attenuation of muscle protein breakdown. This is primarily achieved by spiking insulin levels, as opposed to increasing amino acid availability [ 35 , 36 ]. Studies show that muscle protein breakdown is only slightly elevated immediately post-exercise and then rapidly rises thereafter [ 36 ]. In the fasted state, muscle protein breakdown is significantly heightened at minutes following resistance exercise, resulting in a net negative protein balance [ 37 ]. Although insulin has known anabolic properties [ 38 , 39 ], its primary impact post-exercise is believed to be anti-catabolic [ 40 — 43 ]. The mechanisms by which insulin reduces proteolysis are not well understood at this time. Down-regulation of other aspects of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway are also believed to play a role in the process [ 45 ]. Given that muscle hypertrophy represents the difference between myofibrillar protein synthesis and proteolysis, a decrease in protein breakdown would conceivably enhance accretion of contractile proteins and thus facilitate greater hypertrophy. Accordingly, it seems logical to conclude that consuming a protein-carbohydrate supplement following exercise would promote the greatest reduction in proteolysis since the combination of the two nutrients has been shown to elevate insulin levels to a greater extent than carbohydrate alone [ 28 ]. However, while the theoretical basis behind spiking insulin post-workout is inherently sound, it remains questionable as to whether benefits extend into practice. This insulinogenic effect is easily accomplished with typical mixed meals, considering that it takes approximately 1—2 hours for circulating substrate levels to peak, and 3—6 hours or more for a complete return to basal levels depending on the size of a meal. For example, Capaldo et al. This meal was able to raise insulin 3 times above fasting levels within 30 minutes of consumption. At the 1-hour mark, insulin was 5 times greater than fasting. At the 5-hour mark, insulin was still double the fasting levels. In another example, Power et al. The inclusion of carbohydrate to this protein dose would cause insulin levels to peak higher and stay elevated even longer. Therefore, the recommendation for lifters to spike insulin post-exercise is somewhat trivial. The classical post-exercise objective to quickly reverse catabolic processes to promote recovery and growth may only be applicable in the absence of a properly constructed pre-exercise meal. Moreover, there is evidence that the effect of protein breakdown on muscle protein accretion may be overstated. Glynn et al. These results were seen regardless of the extent of circulating insulin levels. Thus, it remains questionable as to what, if any, positive effects are realized with respect to muscle growth from spiking insulin after resistance training. Perhaps the most touted benefit of post-workout nutrient timing is that it potentiates increases in MPS. Resistance training alone has been shown to promote a twofold increase in protein synthesis following exercise, which is counterbalanced by the accelerated rate of proteolysis [ 36 ]. It appears that the stimulatory effects of hyperaminoacidemia on muscle protein synthesis, especially from essential amino acids, are potentiated by previous exercise [ 35 , 50 ]. There is some evidence that carbohydrate has an additive effect on enhancing post-exercise muscle protein synthesis when combined with amino acid ingestion [ 51 ], but others have failed to find such a benefit [ 52 , 53 ]. However, despite the common recommendation to consume protein as soon as possible post-exercise [ 60 , 61 ], evidence-based support for this practice is currently lacking. Levenhagen et al. Employing a within-subject design,10 volunteers 5 men, 5 women consumed an oral supplement containing 10 g protein, 8 g carbohydrate and 3 g fat either immediately following or three hours post-exercise. A limitation of the study was that training involved moderate intensity, long duration aerobic exercise. In contrast to the timing effects shown by Levenhagen et al. Notably, Fujita et al [ 64 ] saw opposite results using a similar design, except the EAA-carbohydrate was ingested 1 hour prior to exercise compared to ingestion immediately pre-exercise in Tipton et al. Adding yet more incongruity to the evidence, Tipton et al. Collectively, the available data lack any consistent indication of an ideal post-exercise timing scheme for maximizing MPS. It also should be noted that measures of MPS assessed following an acute bout of resistance exercise do not always occur in parallel with chronic upregulation of causative myogenic signals [ 66 ] and are not necessarily predictive of long-term hypertrophic responses to regimented resistance training [ 67 ]. Moreover, the post-exercise rise in MPS in untrained subjects is not recapitulated in the trained state [ 68 ], further confounding practical relevance. Thus, the utility of acute studies is limited to providing clues and generating hypotheses regarding hypertrophic adaptations; any attempt to extrapolate findings from such data to changes in lean body mass is speculative, at best. A number of studies have directly investigated the long-term hypertrophic effects of post-exercise protein consumption. The results of these trials are curiously conflicting, seemingly because of varied study design and methodology. Moreover, a majority of studies employed both pre- and post-workout supplementation, making it impossible to tease out the impact of consuming nutrients after exercise. Esmarck et al. Thirteen untrained elderly male volunteers were matched in pairs based on body composition and daily protein intake and divided into two groups: P0 or P2. Subjects performed a progressive resistance training program of multiple sets for the upper and lower body. Training was carried out 3 days a week for 12 weeks. At the end of the study period, cross-sectional area CSA of the quadriceps femoris and mean fiber area were significantly increased in the P0 group while no significant increase was seen in P2. These results support the presence of a post-exercise window and suggest that delaying post-workout nutrient intake may impede muscular gains. In contrast to these findings, Verdijk et al. Twenty-eight untrained subjects were randomly assigned to receive either a protein or placebo supplement consumed immediately before and immediately following the exercise session. Subjects performed multiple sets of leg press and knee extension 3 days per week, with the intensity of exercise progressively increased over the course of the 12 week training period. No significant differences in muscle strength or hypertrophy were noted between groups at the end of the study period indicating that post exercise nutrient timing strategies do not enhance training-related adaptation. It should be noted that, as opposed to the study by Esmark et al. In an elegant single-blinded design, Cribb and Hayes [ 70 ] found a significant benefit to post-exercise protein consumption in 23 recreational male bodybuilders. Subjects were randomly divided into either a PRE-POST group that consumed a supplement containing protein, carbohydrate and creatine immediately before and after training or a MOR-EVE group that consumed the same supplement in the morning and evening at least 5 hours outside the workout. Results showed that the PRE-POST group achieved a significantly greater increase in lean body mass and increased type II fiber area compared to MOR-EVE. Findings support the benefits of nutrient timing on training-induced muscular adaptations. The study was limited by the addition of creatine monohydrate to the supplement, which may have facilitated increased uptake following training. Moreover, the fact that the supplement was taken both pre- and post-workout confounds whether an anabolic window mediated results. Willoughby et al. Nineteen untrained male subjects were randomly assigned to either receive 20 g of protein or 20 grams dextrose administered 1 hour before and after resistance exercise. Training was performed 4 times a week over the course of 10 weeks. At the end of the study period, total body mass, fat-free mass, and thigh mass was significantly greater in the protein-supplemented group compared to the group that received dextrose. Given that the group receiving the protein supplement consumed an additional 40 grams of protein on training days, it is difficult to discern whether results were due to the increased protein intake or the timing of the supplement. In a comprehensive study of well-trained subjects, Hoffman et al. Seven participants served as unsupplemented controls. Workouts consisted of 3—4 sets of 6—10 repetitions of multiple exercises for the entire body. Training was carried out on 4 day-a-week split routine with intensity progressively increased over the course of the study period. After 10 weeks, no significant differences were noted between groups with respect to body mass and lean body mass. The study was limited by its use of DXA to assess body composition, which lacks the sensitivity to detect small changes in muscle mass compared to other imaging modalities such as MRI and CT [ 76 ]. Hulmi et al. High-intensity resistance training was carried out over 21 weeks. Supplementation was provided before and after exercise. At the end of the study period, muscle CSA was significantly greater in the protein-supplemented group compared to placebo or control. A strength of the study was its long-term training period, providing support for the beneficial effects of nutrient timing on chronic hypertrophic gains. Again, however, it is unclear whether enhanced results associated with protein supplementation were due to timing or increased protein consumption. Most recently, Erskine et al. Subjects were 33 untrained young males, pair-matched for habitual protein intake and strength response to a 3-week pre-study resistance training program. After a 6-week washout period where no training was performed, subjects were then randomly assigned to receive either a protein supplement or a placebo immediately before and after resistance exercise. Training consisted of 6— 8 sets of elbow flexion carried out 3 days a week for 12 weeks. No significant differences were found in muscle volume or anatomical cross-sectional area between groups. The hypothesis is based largely on the pre-supposition that training is carried out in a fasted state. During fasted exercise, a concomitant increase in muscle protein breakdown causes the pre-exercise net negative amino acid balance to persist in the post-exercise period despite training-induced increases in muscle protein synthesis [ 36 ]. Thus, in the case of resistance training after an overnight fast, it would make sense to provide immediate nutritional intervention--ideally in the form of a combination of protein and carbohydrate--for the purposes of promoting muscle protein synthesis and reducing proteolysis, thereby switching a net catabolic state into an anabolic one. Over a chronic period, this tactic could conceivably lead cumulatively to an increased rate of gains in muscle mass. This inevitably begs the question of how pre-exercise nutrition might influence the urgency or effectiveness of post-exercise nutrition, since not everyone engages in fasted training. Tipton et al. Although this finding was subsequently challenged by Fujita et al. These data indicate that even minimal-to-moderate pre-exercise EAA or high-quality protein taken immediately before resistance training is capable of sustaining amino acid delivery into the post-exercise period. Given this scenario, immediate post-exercise protein dosing for the aim of mitigating catabolism seems redundant. The next scheduled protein-rich meal whether it occurs immediately or 1—2 hours post-exercise is likely sufficient for maximizing recovery and anabolism. On the other hand, there are others who might train before lunch or after work, where the previous meal was finished 4—6 hours prior to commencing exercise. This lag in nutrient consumption can be considered significant enough to warrant post-exercise intervention if muscle retention or growth is the primary goal. Layman [ 77 ] estimated that the anabolic effect of a meal lasts hours based on the rate of postprandial amino acid metabolism. However, infusion-based studies in rats [ 78 , 79 ] and humans [ 80 , 81 ] indicate that the postprandial rise in MPS from ingesting amino acids or a protein-rich meal is more transient, returning to baseline within 3 hours despite sustained elevations in amino acid availability. In light of these findings, when training is initiated more than ~3—4 hours after the preceding meal, the classical recommendation to consume protein at least 25 g as soon as possible seems warranted in order to reverse the catabolic state, which in turn could expedite muscular recovery and growth. However, as illustrated previously, minor pre-exercise nutritional interventions can be undertaken if a significant delay in the post-exercise meal is anticipated. An interesting area of speculation is the generalizability of these recommendations across training statuses and age groups. Burd et al. This suggests a less global response in advanced trainees that potentially warrants closer attention to protein timing and type e. In addition to training status, age can influence training adaptations. The mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are not clear, but there is evidence that in younger adults, the acute anabolic response to protein feeding appears to plateau at a lower dose than in elderly subjects. Illustrating this point, Moore et al. In contrast, Yang et al. These findings suggest that older subjects require higher individual protein doses for the purpose of optimizing the anabolic response to training. The body of research in this area has several limitations. First, while there is an abundance of acute data, controlled, long-term trials that systematically compare the effects of various post-exercise timing schemes are lacking. The majority of chronic studies have examined pre- and post-exercise supplementation simultaneously, as opposed to comparing the two treatments against each other. This prevents the possibility of isolating the effects of either treatment. That is, we cannot know whether pre- or post-exercise supplementation was the critical contributor to the outcomes or lack thereof. Another important limitation is that the majority of chronic studies neglect to match total protein intake between the conditions compared. Further, dosing strategies employed in the preponderance of chronic nutrient timing studies have been overly conservative, providing only 10—20 g protein near the exercise bout. More research is needed using protein doses known to maximize acute anabolic response, which has been shown to be approximately 20—40 g, depending on age [ 84 , 85 ]. There is also a lack of chronic studies examining the co-ingestion of protein and carbohydrate near training. Thus far, chronic studies have yielded equivocal results. On the whole, they have not corroborated the consistency of positive outcomes seen in acute studies examining post-exercise nutrition. Another limitation is that the majority of studies on the topic have been carried out in untrained individuals. Muscular adaptations in those without resistance training experience tend to be robust, and do not necessarily reflect gains experienced in trained subjects. It therefore remains to be determined whether training status influences the hypertrophic response to post-exercise nutritional supplementation. A final limitation of the available research is that current methods used to assess muscle hypertrophy are widely disparate, and the accuracy of the measures obtained are inexact [ 68 ]. As such, it is questionable whether these tools are sensitive enough to detect small differences in muscular hypertrophy. Although minor variances in muscle mass would be of little relevance to the general population, they could be very meaningful for elite athletes and bodybuilders. Thus, despite conflicting evidence, the potential benefits of post-exercise supplementation cannot be readily dismissed for those seeking to optimize a hypertrophic response. Practical nutrient timing applications for the goal of muscle hypertrophy inevitably must be tempered with field observations and experience in order to bridge gaps in the scientific literature. With that said, high-quality protein dosed at 0. For example, someone with 70 kg of LBM would consume roughly 28—35 g protein in both the pre- and post exercise meal. Exceeding this would be have minimal detriment if any, whereas significantly under-shooting or neglecting it altogether would not maximize the anabolic response. Due to the transient anabolic impact of a protein-rich meal and its potential synergy with the trained state, pre- and post-exercise meals should not be separated by more than approximately 3—4 hours, given a typical resistance training bout lasting 45—90 minutes. If protein is delivered within particularly large mixed-meals which are inherently more anticatabolic , a case can be made for lengthening the interval to 5—6 hours. This strategy covers the hypothetical timing benefits while allowing significant flexibility in the length of the feeding windows before and after training. Specific timing within this general framework would vary depending on individual preference and tolerance, as well as exercise duration. One of many possible examples involving a minute resistance training bout could have up to minute feeding windows on both sides of the bout, given central placement between the meals. In contrast, bouts exceeding typical duration would default to shorter feeding windows if the 3—4 hour pre- to post-exercise meal interval is maintained. Even more so than with protein, carbohydrate dosage and timing relative to resistance training is a gray area lacking cohesive data to form concrete recommendations. It is tempting to recommend pre- and post-exercise carbohydrate doses that at least match or exceed the amounts of protein consumed in these meals. However, carbohydrate availability during and after exercise is of greater concern for endurance as opposed to strength or hypertrophy goals. Furthermore, the importance of co-ingesting post-exercise protein and carbohydrate has recently been challenged by studies examining the early recovery period, particularly when sufficient protein is provided. Koopman et al [ 52 ] found that after full-body resistance training, adding carbohydrate 0. Subsequently, Staples et al [ 53 ] reported that after lower-body resistance exercise leg extensions , the increase in post-exercise muscle protein balance from ingesting 25 g whey isolate was not improved by an additional 50 g maltodextrin during a 3-hour recovery period. For the goal of maximizing rates of muscle gain, these findings support the broader objective of meeting total daily carbohydrate need instead of specifically timing its constituent doses. Collectively, these data indicate an increased potential for dietary flexibility while maintaining the pursuit of optimal timing. Kerksick C, Harvey T, Stout J, Campbell B, Wilborn C, Kreider R, Kalman D, Ziegenfuss T, Lopez H, Landis J, Ivy JL, Antonio J: International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: nutrient timing. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar. Ivy J, Portman R: Nutrient Timing: The Future of Sports Nutrition. Google Scholar. Candow DG, Chilibeck PD: Timing of creatine or protein supplementation and resistance training in the elderly. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Nutr Metab Lond. Article Google Scholar. Kukuljan S, Nowson CA, Sanders K, Daly RM: Effects of resistance exercise and fortified milk on skeletal muscle mass, muscle size, and functional performance in middle-aged and older men: an mo randomized controlled trial. J Appl Physiol. Lambert CP, Flynn MG: Fatigue during high-intensity intermittent exercise: application to bodybuilding. Sports Med. Article PubMed Google Scholar. MacDougall JD, Ray S, Sale DG, McCartney N, Lee P, Garner S: Muscle substrate utilization and lactate production. Can J Appl Physiol. Robergs RA, Pearson DR, Costill DL, Fink WJ, Pascoe DD, Benedict MA, Lambert CP, Zachweija JJ: Muscle glycogenolysis during differing intensities of weight-resistance exercise. CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Goodman CA, Mayhew DL, Hornberger TA: Recent progress toward understanding the molecular mechanisms that regulate skeletal muscle mass. Cell Signal. Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Nat Cell Biol. Jacinto E, Hall MN: Tor signalling in bugs, brain and brawn. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. Cell Metab. McBride A, Ghilagaber S, Nikolaev A, Hardie DG: The glycogen-binding domain on the AMPK beta subunit allows the kinase to act as a glycogen sensor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. Churchley EG, Coffey VG, Pedersen DJ, Shield A, Carey KA, Cameron-Smith D, Hawley JA: Influence of preexercise muscle glycogen content on transcriptional activity of metabolic and myogenic genes in well-trained humans. Dennis PB, Jaeschke A, Saitoh M, Fowler B, Kozma SC, Thomas G: Mammalian TOR: a homeostatic ATP sensor. Camera DM, West DW, Burd NA, Phillips SM, Garnham AP, Hawley JA, Coffey VG: Low muscle glycogen concentration does not suppress the anabolic response to resistance exercise. Lemon PW, Mullin JP: Effect of initial muscle glycogen levels on protein catabolism during exercise. Blomstrand E, Saltin B, Blomstrand E, Saltin B: Effect of muscle glycogen on glucose, lactate and amino acid metabolism during exercise and recovery in human subjects. J Physiol. Ivy JL: Glycogen resynthesis after exercise: effect of carbohydrate intake. Int J Sports Med. Richter EA, Derave W, Wojtaszewski JF: Glucose, exercise and insulin: emerging concepts. Derave W, Lund S, Holman GD, Wojtaszewski J, Pedersen O, Richter EA: Contraction-stimulated muscle glucose transport and GLUT-4 surface content are dependent on glycogen content. Am J Physiol. Kawanaka K, Nolte LA, Han DH, Hansen PA, Holloszy JO: Mechanisms underlying impaired GLUT-4 translocation in glycogen-supercompensated muscles of exercised rats. PubMed Google Scholar. Berardi JM, Price TB, Noreen EE, Lemon PW: Postexercise muscle glycogen recovery enhanced with a carbohydrate-protein supplement. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Ivy JL, Goforth HW, Damon BM, McCauley TR, Parsons EC, Price TB: Early postexercise muscle glycogen recovery is enhanced with a carbohydrate-protein supplement. Zawadzki KM, Yaspelkis BB, Ivy JL: Carbohydrate-protein complex increases the rate of muscle glycogen storage after exercise. Tarnopolsky MA, Bosman M, Macdonald JR, Vandeputte D, Martin J, Roy BD: Postexercise protein-carbohydrate and carbohydrate supplements increase muscle glycogen in men and women. Jentjens RL, van Loon LJ, Mann CH, Wagenmakers AJ, Jeukendrup AE: Addition of protein and amino acids to carbohydrates does not enhance postexercise muscle glycogen synthesis. Jentjens R, Jeukendrup A: Determinants of post-exercise glycogen synthesis during short-term recovery. Roy BD, Tarnopolsky MA: Influence of differing macronutrient intakes on muscle glycogen resynthesis after resistance exercise. Parkin JA, Carey MF, Martin IK, Stojanovska L, Febbraio MA: Muscle glycogen storage following prolonged exercise: effect of timing of ingestion of high glycemic index food. Fox AK, Kaufman AE, Horowitz JF: Adding fat calories to meals after exercise does not alter glucose tolerance. Biolo G, Tipton KD, Klein S, Wolfe RR: An abundant supply of amino acids enhances the metabolic effect of exercise on muscle protein. Kumar V, Atherton P, Smith K, Rennie MJ: Human muscle protein synthesis and breakdown during and after exercise. Pitkanen HT, Nykanen T, Knuutinen J, Lahti K, Keinanen O, Alen M, Komi PV, Mero AA: Free amino acid pool and muscle protein balance after resistance exercise. Biolo G, Williams BD, Fleming RY, Wolfe RR: Insulin action on muscle protein kinetics and amino acid transport during recovery after resistance exercise. Fluckey JD, Vary TC, Jefferson LS, Farrell PA: Augmented insulin action on rates of protein synthesis after resistance exercise in rats. Denne SC, Liechty EA, Liu YM, Brechtel G, Baron AD: Proteolysis in skeletal muscle and whole body in response to euglycemic hyperinsulinemia in normal adults. Gelfand RA, Barrett EJ: Effect of physiologic hyperinsulinemia on skeletal muscle protein synthesis and breakdown in man. J Clin Invest. Heslin MJ, Newman E, Wolf RF, Pisters PW, Brennan MF: Effect of hyperinsulinemia on whole body and skeletal muscle leucine carbon kinetics in humans. Kettelhut IC, Wing SS, Goldberg AL: Endocrine regulation of protein breakdown in skeletal muscle. Diabetes Metab Rev. Kim DH, Kim JY, Yu BP, Chung HY: The activation of NF-kappaB through Akt-induced FOXO1 phosphorylation during aging and its modulation by calorie restriction. Greenhaff PL, Karagounis LG, Peirce N, Simpson EJ, Hazell M, Layfield R, Wackerhage H, Smith K, Atherton P, Selby A, Rennie MJ: Disassociation between the effects of amino acids and insulin on signaling, ubiquitin ligases, and protein turnover in human muscle. Rennie MJ, Bohe J, Smith K, Wackerhage H, Greenhaff P: Branched-chain amino acids as fuels and anabolic signals in human muscle. Add a small amount of protein to help prevent muscle protein breakdown. Consuming a balanced meal or snack with a higher ratio of carbohydrates to protein can aid in this recovery process. Resistance training weightlifting, bodyweight exercises typically relies on your anaerobic energy system and utilises your glycogen stores for quick, intense bursts of energy. These workouts are primarily aimed at building strength and muscle. Pre-Workout : Before a resistance training session, a balanced combination of proteins and carbohydrates can help fuel your workout and protect against muscle protein breakdown. Post-Workout : After resistance training, aim to consume a meal or snack with a balanced amount of proteins and carbohydrates. The protein will support muscle recovery and growth, while the carbohydrates will replenish your depleted glycogen stores. Endurance training long-distance running, cycling, triathlon requires prolonged energy release and involves both aerobic and anaerobic energy systems. Pre-Workout : For endurance activities, your pre-workout meal should be rich in carbohydrates to maximise your glycogen stores for sustained energy release. Also, include a moderate amount of protein to support muscle function. Post-Workout : Post-endurance training, focus on a recovery meal that includes a higher ratio of carbohydrates to restore glycogen levels, along with adequate protein to facilitate muscle repair. Understanding how your body uses nutrients for different types of workouts can help you make more informed choices about what and when to eat around your training sessions. Remember, individual needs can vary greatly based on your body composition, fitness level, goals, and the intensity and duration of your workouts. But is it a scientifically-backed concept or just a myth? The anabolic window concept proposes that there is a limited time slot, typically stated as up to 30 minutes to 2 hours post-exercise, during which you should consume protein and carbohydrates to maximise muscle repair, growth, and glycogen replenishment. This idea has been prevalent in fitness circles for years and has heavily influenced post-workout nutrition strategies. Several studies, including one published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition , have indeed shown that protein ingestion post-workout can enhance muscle protein synthesis and promote muscle growth. Similarly, carbohydrate intake after exercise is proven to replenish glycogen stores more rapidly. However, the assertion that this must occur within a narrow post-workout window for maximum benefit has been challenged in recent years. Some research, including a systematic review published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition , suggests that this window might be longer than traditionally thought, and that total daily protein and carbohydrate intake might be just as, if not more, important. The timing of nutrient intake around workouts, particularly protein, can still offer benefits, especially for individuals doing multiple training sessions in a day, those training in a fasted state, or those looking to optimise recovery and performance. In conclusion, while the anabolic window is not as rigid as once believed, the principle of nutrient timing still holds value. Balancing your nutrient timing strategies with your total daily intake, dietary quality, and specific fitness goals can help optimise your results. The practice of nutrient timing — strategically timing your intake of protein, carbohydrates, and fats in relation to exercise — has gained considerable attention in both scientific and fitness communities. But how effective is it, really? Overall, research indicates that nutrient timing can indeed be an effective strategy to augment muscle recovery, promote muscle growth, enhance athletic performance, and potentially assist in weight management. This is primarily based on the physiological state the body enters post-exercise, which enhances the uptake and utilisation of nutrients, particularly protein and carbohydrates. A study published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition concluded that protein intake close to resistance-type exercise training enhanced muscle recovery and hypertrophy. Similarly, research in Sports Medicine highlighted the role of post-exercise carbohydrate intake in expediting glycogen resynthesis. However, the emphasis on nutrient timing should not overshadow the importance of total daily intake and quality of diet. A review in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition suggests that total daily protein and carbohydrate intake is a significant factor, potentially more so than the precise timing of nutrient ingestion. Moreover, the benefits of nutrient timing may be more pronounced for certain individuals and circumstances. Those who train multiple times a day, athletes participating in prolonged endurance events, individuals training in a fasted state, or those aiming for optimal muscle recovery and growth might see more noticeable benefits from timed nutrient intake. For personalised advice, consider consulting with a dietitian or a fitness professional. Here are some simple, practical tips to help you optimise your nutrient intake around your workouts. After a workout, especially resistance training, aim to consume grams of high-quality protein. This can help stimulate muscle protein synthesis and promote recovery. Examples include a protein shake, a cup of Greek yoghurt, or a chicken breast. Consuming a carbohydrate-rich meal or snack post-workout can replenish your glycogen stores and enhance recovery. Include sources like whole grains, fruits, or starchy vegetables in your post-workout meal. Hydration plays a crucial role in overall health and exercise performance. Dehydration can hinder your performance and recovery. For some, a pre-workout meal or snack can help fuel a workout and maximise performance. Aim for a balanced snack that includes both protein and carbohydrates. Each person responds differently to food timing around exercise. What works well for one person might not work as well for another. Listen to your body and adjust your nutrient timing to suit your individual needs, workout intensity, and fitness goals. While nutrient timing can have benefits, your total daily intake of protein, carbohydrates, fats, and overall calories plays a more significant role in supporting your fitness goals and overall health. Remember, these are general guidelines, and individual needs may vary. Consulting a registered dietitian or a certified fitness professional can help you personalise your nutrition plan to your specific needs and goals. Your fitness journey could inspire others to lead healthier lives! Navigating the world of fitness and nutrition can be complex, but understanding the principles of nutrient timing can give you an edge in optimising your workout performance and recovery. To recap the key points from our comprehensive exploration:. Remember, individual needs can vary, and the best approach to nutrition and exercise is often personalised. Consulting with a dietitian or a certified fitness professional can provide you with tailored guidance. Happy training, and remember, your fitness journey is a marathon, not a sprint! The fitness industry is a dynamic and rewarding field, allowing you to inspire and guide others on their wellness journeys. At Educate Fitness, we offer a range of courses designed to equip you with the skills, knowledge, and qualifications needed to excel in the fitness industry. Whether you aspire to work in a gym environment or offer personalised training services, we have a course for you. So, why not take that passion for fitness to the next level? The next step in your fitness journey awaits! Table of Contents. Phases of Nutrient Timing Nutrient timing is typically broken down into three distinct phases: the Energy Phase, the Anabolic Phase, and the Growth Phase. The Energy Phase Pre-Workout and Intra-Workout The energy phase starts roughly one to four hours before your workout and continues through the duration of your exercise session. The Growth Phase Post-Anabolic Phase The growth phase encompasses the remainder of the day outside the energy and anabolic phases. The Science Behind Nutrient Timing The concept of nutrient timing is based on physiological principles and is backed by numerous scientific studies. Carbohydrate Replenishment Glycogen, a form of carbohydrate stored in muscles, is a primary fuel source during high-intensity exercise. How Nutrient Timing Contributes to Fitness Goals The strategic implementation of nutrient timing can be a powerful tool to help reach a variety of fitness goals. Muscle Growth and Strength One of the primary goals for many gym-goers and athletes is to increase muscle mass and strength. Weight Loss or Body Fat Reduction While total caloric intake ultimately determines weight loss or gain, nutrient timing can play a part in optimising body composition and helping with fat loss. Improved Athletic Performance For athletes, nutrient timing can significantly impact performance. Tailoring Nutrient Timing Strategies for Different Exercise Types Nutrient timing is not a one-size-fits-all strategy. Resistance Training Resistance training weightlifting, bodyweight exercises typically relies on your anaerobic energy system and utilises your glycogen stores for quick, intense bursts of energy. Endurance Training Endurance training long-distance running, cycling, triathlon requires prolonged energy release and involves both aerobic and anaerobic energy systems. The Anabolic Window: Myth or Reality? Nutrient Timing: Effective or Not? |

| The effect of protein timing on muscle strength and hypertrophy: a meta-analysis | J Appl Physiol. The first is a rapid segment of muscle repair and growth that lasts for up to 4 hours. Protein helps muscles recover faster, which means you'll be able to train harder and more frequently than if you were not getting enough protein in your diet. Balancing your nutrient timing strategies with your total daily intake, dietary quality, and specific fitness goals can help optimise your results. Staples AW, Burd NA, West DW, Currie KD, Atherton PJ, Moore DR, Rennie MJ, Macdonald MJ, Baker SK, Phillips SM: Carbohydrate does not augment exercise-induced protein accretion versus protein alone. Refeeds are the name given to days where more calories and carbs are eaten. |

Versuchen Sie, die Antwort auf Ihre Frage in google.com zu suchen

sehr bemerkenswert topic

ich beglückwünsche, Sie hat der bemerkenswerte Gedanke besucht