Boosting immune resilience -

Stress is the number one enemy of immunity. Abhyanga also corrects the functioning of the lymphatic system that is responsible to keep our immune system robust.

Clarified butter is now popular enough in the west for the healthy fat that it is, as more research shows its myriad benefits in improving digestion, eyesight, detoxifying the body and building resilience. Ghee, when made using the milk of finest breeds of grass-fed cows, whose well-being is looked into, reflects in the purity and texture of the ghee.

Ghee absorbs fat soluble vitamins like A,D,E and K into the body. It is known for ages to support a healthy immunity and comes loaded with many health benefits. Yoga works up each and every aspect of our physical body and mind, responsible for a robust immunity.

It refines the functioning of the lymph nodes that help expel waste from the cellular level in the body. Yoga helps calm your mind and nervous system, resetting the system to our real nature which is peace and inner strength.

Yogic practices do not let aama accumulate in the body that weaken the immunity and make the body a fertile ground for diseases and illnesses to flourish.

Here are a few yoga poses you can choose to practice to work up a sluggish immune system. Like we said earlier, stress is the number one enemy of our immune system, as chronic stress means an overactive sympathetic nervous, that keeps the body constantly in the fight or flight mode, in which state, the vitals of our body are tense and rising.

When stress persists, it starts to break down and weaken the immune response. This can further make it difficult for the body to respond to viruses and other foreign pathogens. An effective antidote to stress, recommended by the WHO to stay healthy, is meditation.

If you are a beginner, you can start off with simple short guided meditations. Make sure you sit for meditation on an empty stomach and not after having downed a heavy meal. Or you can practice yoga nidra meditation , which is a meditation in restful awareness that gives you deep rest and relaxes your body in just 20 minutes.

This content on the Sri Sri Tattva blog is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, or other qualified health providers with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Any links to third party websites is provided as a convenience only and the Sri Sri Tattva Blog is not responsible for their content.

New customer? Create your account Lost password? Your cart is empty. Personal Care Oral Care Face Care Skin care Hair Care Cleansing Bars. Natural Foods Ojasvita with 7 Herbs Chyawanprash Karela Jamun Juice Amla Candy Chocolates. Speciality Products Gift Cards Incense Sticks g Incense Sticks 20g Incense Cones Dhoop Sticks.

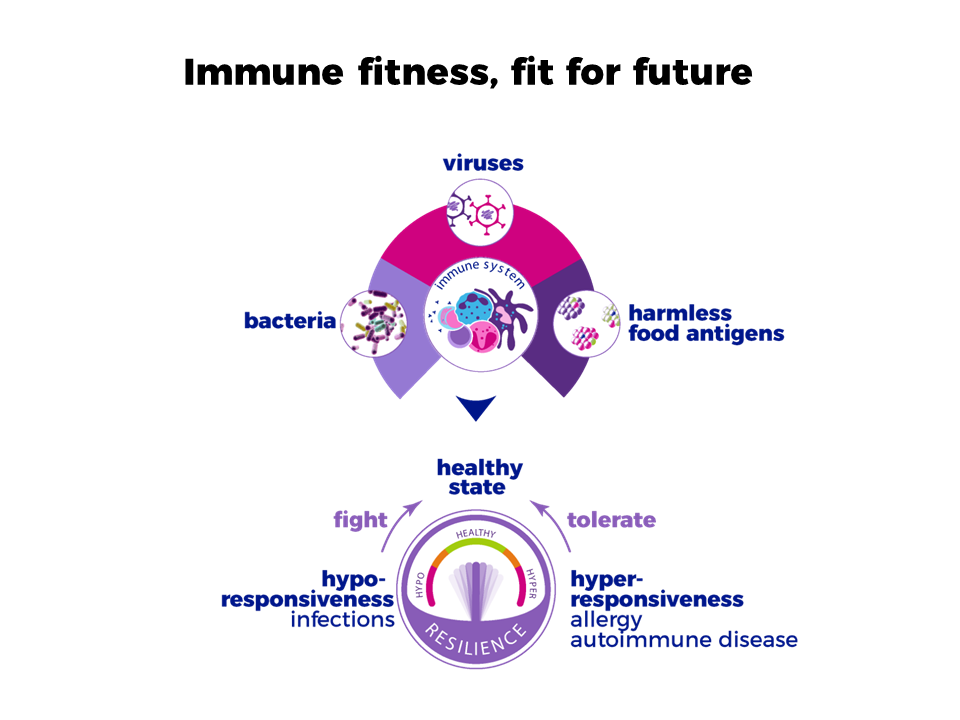

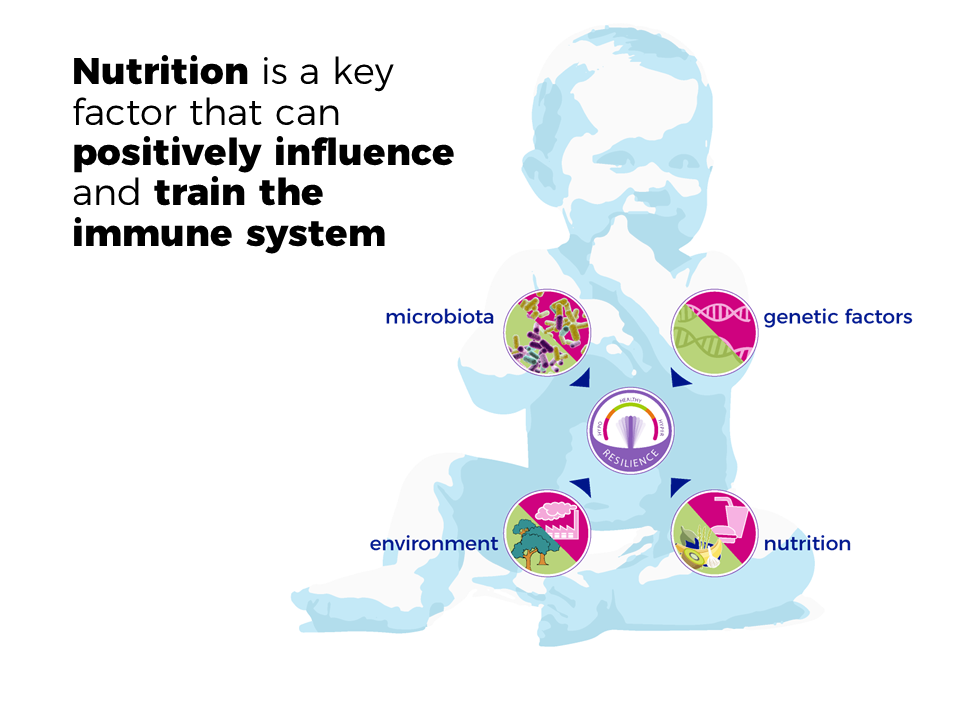

Food · Digestible and well cooked meals Go for easy to digest but cooked hot meals and avoid fried, cold or sweet foods. Abhyanga or self-massage According to Ayurveda, a common reason for low immunity is the buildup of toxins in our body in the form of aama. These differences may account for why some younger people are predisposed to disease and shorter lifespans while some elderly people remain unusually healthy and live longer than their peers.

Second, reducing exposure to immune stressors may maintain optimal IR or give people with low or moderate IR the opportunity to regain optimal IR, thereby decreasing risk of severe disease. Fourth, it may make sense to balance the intervention and placebo arms of clinical trials by both IR status and common factors such as age and sex when testing interventions dependent on controlling inflammation and preserving or rapidly restoring immune activity associated with longevity.

Finally, strategies for boosting IR and reducing recurrent immune stressors may help address racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in diseases such as cancer and viral infections like COVID Reference: SK Ahuja, et al. Immune resilience despite inflammatory stress promotes longevity and favorable health outcomes including resistance to infection.

Nature Communications DOI: Skip to Back. Resources for Researchers. Research in NIAID Labs. Division of Intramural Research Labs. Research at Vaccine Research Center.

Clinical Research. Infectious Diseases. Research Funded by NIAID. Managing Symptoms. Understanding Triggers. Autoimmune Diseases. Disease-Specific Research. Information for Researchers. Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome ALPS. Long COVID and MIS-C. Strategic Planning.

Origins of Coronaviruses. Dengue Fever. Shiga Toxin-Producing E. coli STEC. Researching Ebola in Africa. Photo Essay. Food Allergy. Why Food Allergy is a Priority for NIAID. Research Approach. Risk Factors. Diagnosing Food Allergy.

Treatment for Living with Food Allergy. Fungal Diseases. Group A Streptococcal Infections. Types of Group A Strep. Vaccine Research. Vaccine Development. Basic Research. Leprosy Hansen's Disease. Research Next Steps. Lyme Disease. How NIAID is Addressing Lyme Disease. Antibiotic Treatment. Chronic Lyme Disease.

Featured Research. Scientific Resources. Primary Immune Deficiency Diseases PIDDs. Types of PIDDs. Talking to Your Doctor. Therapeutic Approaches. Animal Prion Diseases and Humans. Respiratory Syncytial Virus RSV. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever.

Schistosomiasis Bilharzia. Research in Endemic Regions. Sexually Transmitted Infections STIs. Areas of Research. STAT3 Dominant-Negative Disease. Tickborne Diseases. Tuberculosis Drugs. West Nile Virus. Zika Virus. Why NIAID Is Researching Zika Virus.

Addressing Zika Virus. Types of Funding Opportunities. NIAID Research Priorities. See Funded Projects. Sample Applications. Determine Eligibility. Second, while expression levels of SAS-1 and IMM-AGE declined and those of MAS-1 increased with age Supplementary Fig.

Thus, the age-associated changes in SAS-1 and MAS-1 levels appeared to be more closely related to accumulated antigenic experience than the direct effects of age per se. Together, these findings and the gene composition of the signatures Fig. SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low , SAS-1 high -MAS-1 high , SAS-1 low -MAS-1 low , and SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high profiles are considered as representative of IC high -IF low , IC high -IF high , IC low -IF low , and IC low -IF high states, respectively Fig.

First, akin to the age-associated shift from IHG-I to non-IHG-I grades Fig. Second, akin to the overrepresentation of IHG-I in females across age strata Fig. SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high profiles were more prevalent in females than males Fig. These findings were consistent with our observation that, across all ages in the FHS, females compared with males preserved higher levels of SAS-1 and lower levels of MAS-1 Supplementary Fig.

Conversely, representation of SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high was progressively greater with the a, b, and c subgrades of IHG-II and IHG-IV Fig.

IHG-III lacked representation of the SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile. Thus, IHG-I was hallmarked by nearly complete representation of the SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile and underrepresentation of the SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high profile. In contrast, IHG-IIc and IHG-IVc were hallmarked by complete representation of the SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high profile and absence of the SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile.

IHG-IIa had some representation of the SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile. Congruent with these findings, expression of SAS-1 was higher, whereas expression of MAS-1 was lower in IHG-I vs. the other grades in three distinct cohorts Supplementary Fig.

In the COVID cohort, there was a stepwise decrease in IHG-I with age Fig. Paralleling these findings with IHG-I, the representation of SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low i decreased with age Fig. hospitalized survivors and absent in nonsurvivors Fig. Conversely, representation of the SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high profile was higher in older persons, nonsurvivors, and individuals with IHG-IV; intermediate in hospitalized survivors and those with IHG-II; and lower or absent in nonhospitalized survivors or those with IHG-I Fig.

Fourth, consistent with our finding that some younger persons develop non-IHG-I grades that are more common in older persons Figs. Furthermore, the relative representation of SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low vs. Hence, individuals with a survival disadvantage COVID nonsurvivors, patients with AIDS share the hallmark features found in IHG-IIc and IHG-IVc, namely, absence of SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low and enrichment of SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high Fig.

We suggest that i the SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile is a transcriptomic proxy for IHG-I and that both of these metrics of optimal IR are overrepresented in females Fig.

Compared with the SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile, the hazard of dying, after controlling for age and sex, was higher and similar in persons with the SAS-1 high -MAS-1 high and SAS-1 low -MAS-1 low profiles and highest in persons with the SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high profile Fig.

Correspondingly, SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high was overrepresented and SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low was underrepresented at baseline in nonsurvivors Fig.

First, among older FHS participants, females lived longer than males, and levels of SAS-1 and MAS-1 further stratified survival rates Supplementary Fig. The survival rates in older 66—92 years persons were highest in females with SAS-1 high or MAS-1 low , intermediate in females with SAS-1 low or MAS-1 high and males with SAS-1 high or MAS-1 low , and lowest in males with SAS-1 low or MAS-1 high Supplementary Fig.

This survival hierarchy and our findings in Fig. c Model: age, sex, and immunologic resilience IR levels influence lifespan. d Sepsis 1 comprises healthy controls and meta-analysis of patients with community-acquired pneumonia CAP and fecal peritonitis FP stratified by sepsis response signature groups G1 and G2 associated with higher and lower mortality, respectively.

Sepsis 2 comprises healthy controls and patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome SIRS , sepsis, and septic shock survivors S and nonsurvivors NS. P values asterisks, ns for participants with SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high at pre-ARI right are for their cross-sectional comparison to the profiles at the corresponding timepoints for participants with SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low at pre-ARI middle.

f Schema of the timing of gene expression profiling in experimental intranasal challenges with respiratory viral infection in otherwise healthy young adults with data presented in panels g and h.

T, time. g Participants inoculated intra-nasally with respiratory syncytial virus RSV , rhinovirus, or influenza virus stratified by symptom status and sampling timepoint. symptomatic, Asymp. h Participants inoculated intra-nasally with influenza virus stratified by symptom status and sampling timepoint.

i Individuals with severe influenza infection requiring hospitalization collected at three timepoints, overall, and by age strata and severity. Patients were grouped by increasing severity levels: no supplemental oxygen required, oxygen by mask, and mechanical ventilation. Cohort characteristics and sources of biological samples and gene expression profile data are in Supplementary Data 13a.

Based on gene expression profiles obtained at baseline admission , Knight and colleagues categorized four cohorts of individuals into sepsis risk groups that predicted mortality vs.

survival in individuals admitted to intensive care units with severe sepsis due to community-acquired pneumonia or fecal peritonitis 37 , Our evaluations revealed that, irrespective of age, the survival-associated SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile was highly underrepresented, whereas SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high and SAS-1 low -MAS-1 low profiles were disproportionately overrepresented in the sepsis risk group associated with mortality G1 group vs.

survival G2 group Fig. Thus, consistent with our model Fig. We next examined whether asymptomatic ARI was associated with the IR erosion-resistant phenotype, i. symptomatic infection after viral challenge at two timepoints: baseline T1 vs. when symptomatic patients had peak symptoms T2 Fig.

Figure 8g shows the combined results of three different viral challenges influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus. Among symptomatic participants, SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high was enriched at T2 vs. T1 Fig. In contrast, among persons who remained asymptomatic, proportions of the SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high profile did not change substantially between T1 and T2; instead at T2, there was a significant enrichment of SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low compared to symptomatic participants Fig.

Similar results were observed in another study in which participants were challenged with influenza virus Fig. Supporting these findings in humans, among pre-Collaborative Cross-RIX mice strains infected with influenza, SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low was overrepresented, whereas SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high was underrepresented in strains that manifested histopathologic features of mild low response vs.

severe high response infection Supplementary Fig. Paralleling the time series shown in Fig. However, regardless of age, the hallmark of less-severe vs. most-severe influenza infection was the capacity to reconstitute a survival-associated SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile more quickly Fig.

Figure 9a synthesizes the key findings from study phases 1, 2, and 3. Viral challenge studies in humans Fig. rapid restoration of the survival-associated IC high -IF low state SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile during the convalescence phase Fig.

Ag antigenic, F female, H high, IC immunocompetence, IF inflammation, L low, M male b IR erosion-resistant and IR erosion-susceptible phenotypes based on experimental models. c Correlation r ; Pearson between expression levels of genes within SAS-1 and MAS-1 signatures with levels of an indicator for T-cell responsiveness, T-cell dysfunction, and systemic inflammation.

d , e Levels of the indicated immune traits by IHGs in d sooty mangabeys seropositive for simian immunodeficiency virus SIV and e SIV-seronegative Chinese rhesus macaques. Comparisons were made between IHG-I vs.

IHG-III and IHG-II vs. To further support the idea that the SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile tracks an IC high -IF low state, we determined the correlation between expression levels of genes comprising SAS-1 and MAS-1 with indicators of T-cell responsiveness and dysfunction in peripheral blood 8 , 43 , as well as systemic inflammation plasma IL-6, a biomarker of age-associated diseases and mortality 44 , 45 , 46 Fig.

Genes correlating positively with T-cell responsiveness and negatively with T-cell dysfunction or plasma IL-6 levels were considered to have pro-IR functions; genes with the opposite attributes were considered to have IR-compromising functions Fig. We found that SAS-1 was enriched for genes whose expression levels correlated positively with pro-IR functions; several of these genes have essential roles in T-cell homeostasis e.

Compared with SAS-1, MAS-1 was enriched for genes whose expression levels correlated with IR-compromising functions e. These associations, coupled with the distribution patterns of the IR metrics across age, raised the possibility that levels of immune traits differed by i IR IHG status, after controlling for age age-independent vs.

ii age, regardless of IR IHG status age-dependent , vs. iii both. Additionally, because we observed evolutionary parallels between humans and nonhuman primates Figs. Trait levels in both species differed to a greater extent by IHG status than age Supplementary Data Thus, CD8-CD4 disequilibrium grades IHG-III and IHG-IV were highly prevalent in nonhuman primates Fig.

In general, IHG-I appeared to be associated with a better immune trait profile e. Contrary to nonhuman primates, CD8-CD4 equilibrium grades IHG-I and IHG-II vs.

disequilibrium grades IHG-III or IHG-IV are much more prevalent across age in humans Fig. However, emphasizing evolutionary parallels, we identified similar traits associated with IHG status after controlling for age in both humans and nonhuman primates.

Group 1 comprised 13 immune traits whose levels differed between CD8-CD4 equilibrium vs. disequilibrium grades IHG-I vs. IHG-III or IHG-II vs IHG-IV , after controlling for age and sex. Group 3 comprised 10 immune traits that differed by attributes of both groups 1 and 2 after controlling for sex.

Group 4 neutral comprised 30 immune traits that did not differ by group 1 or 2 attributes Fig. Within each group, traits were clustered into signatures according to whether their levels were higher or lower with IHG-III or IHG-IV, after controlling for age and sex; by age in older or younger persons with IHG-I or IHG-II, after controlling for sex; both; or neither.

cDC, conventional dendritic cells. Two arrows indicate both comparisons for IHG-I vs. IHG-IV or age within IHG-I and IHG-II are significant, one arrow indicates only one of the comparisons for IHG status or age is significant. b Representative traits by age in persons with IHG-I or IHG-II and by IHG status.

Comparisons for the indicated traits were made between IHG-I vs. Median number of individuals evaluated by IHG status and age within IHG-I or IHG-II.

ns nonsignificant. c Linear regression was used to analyze the association between log 2 transformed cell counts outcome with age and IHG status predictors.

FDR, false discovery rate P values adjusted for multiple comparisons. d Model differentiating features of processes associated with lower immune status that occur due to aging or via erosion of IR.

SAS-1, survival-associated signature-1; MAS-1, mortality-associated signature Figure 10b shows that the levels of a representative trait in signature 6 naïve CD8 bright differed between older vs. younger persons with IHG-I or IHG-II but did not differ by IHG status.

Thus, group 2 immune traits represent traits that are associated with aged CD8-CD4 equilibrium. Additional trait features of Groups 1—4 are discussed Supplementary Note 8.

Thus, suggesting evolutionary parallels, we identified similar immunologic features e. However, since the prevalence of IHG-III or IHG-IV increases with age Fig.

Our study addresses a fundamental conundrum. Conversely, why do some older persons resist manifesting these attributes? This failure indicates the IR erosion-susceptible phenotype. We examined IR levels and responses in varied human and nonhuman cohorts that are representative of different types and severity of inflammatory antigenic stressors.

The sum of our findings supports our study framework that optimal IR is an indicator of successful immune allostasis adaptation when experiencing inflammatory stressors, correlating with a distinctive immunocompetence-inflammation balance IC high -IF low that associates with superior immunity-dependent health outcomes, including longevity Fig.

This IR degradation correlates with a gene expression signature profile SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high tracking an IC low -IF high status linked to mortality both during aging and COVID, as well as immunosuppression e.

Despite clinical recovery from such common viral infections, some younger adults were unable to reconstitute optimal IR. However, since the prevalence of the SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high profile increases steadily with age, it may give the misimpression that this profile relates to the aging process vs.

IR degradation. To test our study framework Fig. These complementary metrics provide an easily implementable method to monitor the IR continuum irrespective of age Figs.

Paralleling the observation that females manifest advantages for immunocompetence and longevity 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , the IR erosion-resistant phenotype was more common in females including postmenopausal. Congruently, immune traits associated with some nonoptimal IR metrics were similar in humans and nonhuman primates.

Additionally, in Collaborative Cross-RIX mice, the IR erosion-resistant phenotype was associated with resistance to lethal Ebola and severe influenza infection. We accrued direct evidence of the benefits of optimal IR during exposure to a single inflammatory stressor by examining young adults during experimental intranasal challenge with common respiratory viruses e.

The hallmark of asymptomatic status after intranasal inoculation of respiratory viruses was the capacity to preserve, enrich, or rapidly restore the survival-associated SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile Figs. Findings noted on longitudinal monitoring of IR degradation and reconstitution during natural infection with common respiratory viruses supported this possibility.

During recovery, reconstitution of optimal IR was greater and faster in persons who before infection had the survival-associated SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low vs. the SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high profile Fig. However, despite the elapse of several months from initial infection, some younger persons with the SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile before infection failed to reconstitute this profile exemplifying residual deficits in IR Fig.

An impairment in the capacity for reconstitution of optimal IR was also observed in prospective cohorts with other inflammatory contexts FSWs, COVID, HIV infection. These findings support our viewpoint that the deviation from optimal IR that tends to occur with age could be due to an impairment in the reconstitution of IR in individuals with the IR erosion-susceptible phenotype Fig.

There is significant interest in identifying host genetic factors that mediate resistance to acquiring SARS-CoV-2 or developing severe COVID 59 , 60 , We are currently investigating whether failure to reconstitute optimal IR after acute COVID may contribute to postacute sequelae.

Resistance to HIV acquisition despite exposure to the virus is a distinctive trait 62 observable in some FSWs. Among FSWs with comparable levels of risk factor-associated antigenic stimulation, HIV seronegativity was an indicator of the IR erosion-resistant phenotype, whereas seropositivity was an indicator of the IR erosion-susceptible phenotype.

Having baseline IHG-IV, a nonoptimal IR metric, associated with a nearly 3-fold increased risk of subsequently acquiring HIV, after controlling for level of risk factors. We found that a subset of FSWs had the capacity for preservation of optimal IR, both before and after HIV infection.

By analogy, we suggest that CMV seropositivity may have similar indicator functions Supplementary Notes 3 , 9. The IR framework points to the commonalities in the HIV and COVID pandemics. Our findings suggest that these pandemics may be driven by individuals who had IR degradation before acquisition of viral infection.

With respect to the HIV pandemic, nonoptimal IR metrics are overrepresented in persons with behavioral and nonbehavioral risk factors for HIV, and these metrics predict an increased risk of HIV acquisition. Correspondingly, HIV burden is greater in geographic regions where the prevalence of nonbehavioral risk factors is also elevated e.

With respect to the COVID pandemic, the proportion of individuals preserving optimal IR metrics decreases with age and age serves as a dominant risk factor for developing severe acute COVID Controlling for age, the likelihood of being hospitalized was significantly lower in individuals preserving optimal IR at diagnosis with COVID Thus, individuals with the IR erosion-susceptible phenotype may have contributed substantially to the burden of these pandemics.

Our study has several limitations expanded limitations in Supplementary Note The primary limitation is our inability to examine the varied clinical outcomes assessed here in a single prospective human cohort. Such a cohort that spans all ages with these varied inflammatory stressors and outcomes is nearly impossible to accrue, necessitating the juxtaposition of findings from varied cohorts.

Additionally, we were unable to evaluate immune traits in peripheral blood samples bio-banked from the same individual when they were younger vs.

However, we took several steps to mitigate this limitation discussed in Supplementary Notes 2 , 8. However, our findings satisfy the nine Bradford-Hill criteria 65 , the most frequently cited framework for causal inference in epidemiologic studies Supplementary Note We acknowledge that, in addition to inflammatory stressors, the changes in IR metrics observed during aging Figs.

Possible confounders regarding the generation of the IHGs and their distribution patterns in varied settings of increased antigenic stimulation are discussed Supplementary Notes 1 , 2 , 3 and 6. While we focused on the association between antigenic stimulation associated with inflammatory stressors and shifts in IHG status, psychosocial stressors may contribute, as they associate with age-related T lymphocyte percentages in older adults However, the latter lymphocyte changes can be indirect, as psychosocial stressors may predispose to infection 68 , As a final limitation, we could not evaluate whether eroded IR mitigates autoimmunity.

Supporting our conclusion that age-independent mechanisms contribute to IR status, we provide evidence that host genetic factors in MHC locus associate with the IR erosion phenotypes Supplementary Note 5.

age Fig. First, while a significant effort is placed on targeting the immune traits associated with age, we show that immune traits group into those associated i uniquely with IR status irrespective of age, ii uniquely with age, and iii both age and IR status Fig.

Some of the immune traits that associate with uniquely nonoptimal IR metrics have been misattributed to age e. Hence, a comparison of immune traits between younger and older persons conflates these groupings, obscuring the immune correlates of age.

Second, the reversibility of eroded IR suggests that immune deficits linked to this erosion are separable from those linked directly to the aging process and may be more amenable to reversal. However, our findings in FSWs and during natural respiratory viral infections indicate that this reversal may take months to years to occur.

Additionally, data from FSWs and sooty mangabeys illustrate that multiple sources of inflammatory stress have additive negative effects on IR status Fig. Hence, reconstitution of optimal IR may require cause-specific interventions.

In summary, our findings support the principles of our framework Fig. Irrespective of these factors, most individuals do not have the capacity to preserve optimal IR when experiencing common inflammatory insults such as symptomatic viral infections. Deviations from optimal IR associates with an immunosuppressive-proinflammatory, mortality-associated gene expression profile.

This deviation is more common in males. Those individuals with capacity to resist this deviation or who during the recovery phase rapidly reconstitute optimal IR manifest health and survival advantages. However, under the pressure of repeated inflammatory antigenic stressors experienced across their lifetime, the number of individuals who retain capacity to resist IR degradation declines.

How might these framework principles inform personalized medicine, development of therapies to promote immune health, and public health policies?

First, individuals with suboptimal or nonoptimal IR can potentially regain optimal IR through reduction of exposure to infectious, environmental, behavioral, and other stressors. Second, IR metrics provide a means to gauge immune health regardless of age, sex, and underlying comorbid conditions.

Thus, early detection of individuals with IR degradation could prompt a work-up to identify the underlying inflammatory stressors. Third, balancing trial and placebo arms of a clinical trial for IR status may mitigate the confounding effects of this status on outcomes that are dependent on differences in immunocompetence and inflammation.

Fourth, while senolytic agents are being investigated for the reversal of age-associated pathologies 75 , the findings presented herein provide a rationale to consider the development of strategies that, by targeting the IR erosion-susceptible phenotype, may improve vaccine responsiveness, healthspan, and lifespan.

Finally, population-level differences in the prevalence of IR metrics may help to explain the racial, ethnic, and geographic distributions of diseases such as viral infections and cancers. Hence, strategies for improving IR and lowering recurrent inflammatory stress may emerge as high priorities for incorporation into public health policies.

All studies were approved by the institutional review boards IRBs at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and institutions participating in this study. The IRBs of participating institutions are listed in the reporting summary.

All studies adhered to ethical and inclusion practices approved by the local IRB. The cohorts and study groups Fig. The SardiNIA study investigates genotypic and phenotypic aging-related traits in a longitudinal manner. The main features of this project have been described in detail previously 9 , 76 , All residents from 4 towns Lanusei, Arzana, Ilbono, and Elini in a valley in Sardinia Italy were invited to participate.

Immunophenotype data from participants age 15 to years were included in this study. Details provided in Supplementary Information Section 1. The Majengo sex worker cohort 17 is an open cohort dedicated to better understanding the natural history of HIV infection, including defining immunologic correlates of HIV acquisition and disease progression.

The present study comprised initially HIV-negative FSWs with data available for analysis and were evaluated from the time they were enrolled see criteria in Supplementary Fig. Of these, subsequently seroconverted. The characteristics of these FSWs are listed in Supplementary Data 4a. The association of risk behavior e.

Among these, 53 subsequently seroconverted. Prior to seroconversion, the 53 FSWs were followed for The characteristics of these FSWs are listed in Supplementary Data 4b.

To investigate the associations of IHG status with cancer development, we assessed the hazard of developing CSCC within a predominantly White cohort of long-term RTRs. A total of RTRs with available clinical and immunological phenotype were evaluated.

The characteristics of the RTRs are as described previously 15 and summarized in Supplementary Data 5. Briefly, 65 eligible RTRs with a history of post-transplant CSCC were identified, of whom 63 were approached and 59 participated. Seventy-two matched eligible RTRs without a history of CSCC were approached and 58 were recruited.

Fifteen percent of participants received induction therapy at the time of transplant, and 80 percent had received a period of dialysis prior to transplantation. haematobium urinary tract infection were from a previous study Briefly, all participants were examined by ultrasound for S.

haematobium infection and associated morbidity in the Msambweni Division of the Kwale district, southern Coast Province, Kenya, an area where S.

haematobium is endemic. No community-based treatment for schistosomiasis had been conducted during the preceding 8 years of enrollment in this population.

From this initial survey, we selected all children 5—18 years old residing in 2 villages, Vidungeni and Marigiza, who had detectable bladder pathology and S. haematobium infection. The HIV-seronegative UCSD cohort was accessed from HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center, UCSD, and derived from the following three resources: a those who enrolled as a normative population for ongoing studies funded by the National Institute of Mental Health; b those who enrolled as a normative population for studies funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse; and c those who enrolled as HIV— users of recreational drugs for studies funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

In the present study, we evaluated participants pooled from the three abovementioned sources. This was a prospective observational cohort study of patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 evaluated at the Audie L. Murphy VA Medical Center, South Texas Veterans Health Care System STVHCS , San Antonio, Texas, from March 20, , through November 15, The cohort characteristics and samples procedures are described in Supplementary Data 2 and Supplementary Data 7.

The cohort features of a smaller subset of patients studied herein and samples procedures have been previously described 6. COVID progression along the severity continuum was characterized by hospitalization and death. Standard laboratory methods in the Flow Cytometry Core of the Central Pathology Laboratory at the Audie L.

The overview of this cohort is shown in Supplementary Fig. All measurements evaluated in the present study were conducted prior to the availability of COVID vaccinations. RNA-Seq was performed on a subset of this cohort as previously described 6.

These participants were recruited between June and June and then followed prospectively. Details of the cohort are as described previously 7. We evaluated only participants in whom an estimated date of infection could be calculated through a series of well-defined stepwise rules that characterize stages of infection based on our previously described serologic and virologic criteria 7.

Of the participants, were evaluated in the present study while they were therapy-naïve see criteria in Supplementary Fig. The inclusion criteria are outlined in Supplementary Fig.

Participants in the cohort self-selected ART or no ART, and those who chose not to start therapy were followed in a manner identical to those who chose to start ART. Rules of computing time to estimated date of infection are as reported by us previously 7. The US Military HIV Natural History Study is designated as the EIC.

This is an ongoing, continuous-enrollment, prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study conducted through the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program.

The EIC has enrolled approximately active-duty military service members and beneficiaries since at 7 military treatment facilities MTFs throughout the United States. The US military medical system provides comprehensive HIV education, care, and treatment, including the provision of ART and regular visits with clinicians with expertise in HIV medicine at MTFs, at no cost to the patient.

Mandatory periodic HIV screening according to Department of Defense policy allowed treatment initiation to be considered at an early stage of infection before it was recommended practice.

Eighty-eight percent of the participants since have documented seroconversion i. In the present study, of EIC participants were available for evaluation Supplementary Fig. Additional details of the SardiNIA 9 , 76 , 77 , FSW-MOCS 17 , PIC-UCSD 7 , RTR cohort 15 , S.

haematobium -infected children cohort 78 , and EIC 8 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 have been described previously. Some features of the entire populations or subsets of the SardiNIA, COVID, SLE Supplementary Information Section 8. One hundred sixty sooty mangabeys were evaluated in the current study.

Of these, 50 were SIV seronegative SIV— and were naturally infected with SIV Figs. Data from a subset of these sooty mangabeys have been reported by Sumpter et al.

All sooty mangabeys were housed at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center and maintained in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

In uninfected animals, negative SIV determined by PCR in plasma confirmed the absence of SIV infection. Other immune traits studied are reported in Supplementary Data Forty-seven male and 40 female SIV— Chinese rhesus macaques from a previous study were evaluated Fig.

All animals were colony-bred rhesus macaques M. mulatta of Chinese origin. All animals were without overt symptoms of disease tumors, trauma, acute infection, or wasting disease ; estrous, pregnant, and lactational macaques were excluded.

In a study by Rasmussen et al. Different strains were crossed with one another to generate CC-RIX F1 progeny. We selected those cutoffs based on the following rationale. Additional details regarding the IHGs are described in Supplementary Note 1.

Immune correlates markers that associated with IHG status vs. age in the SardiNIA cohort were assessed on fresh blood samples. A set of multiplexed fluorescent surface antibodies was used to characterize the major leukocyte cell populations circulating in peripheral blood belonging to both adaptive and innate immunity.

Briefly, with the antibody panel designated as T-B-NK in Supplementary Data 12 , we identified T-cells, B-cells, and NK-cells and their subsets.

We also used the HLA-DR marker to assess the activation status of T and NK cells. The regulatory T-cell panel Treg in Supplementary Data 12 was used to characterize regulatory T-cells subdivided into resting, activated, and secreting nonsuppressive cells 96 , Moreover, in selected T-cell subpopulations, we assessed the positivity for the ectoenzyme CD39 and the CD28 co-stimulatory antigen Finally, by the circulating dendritic cells DC panel, we divided circulating DCs into myeloid conventional DC, cDC and plasmacytoid DCs pDC and assessed the expression of the adhesion molecule CD62L and the co-stimulatory ligand CD86 , The circulating DC panel is labelled DC in Supplementary Data Detailed protocols and reproducibility of the measurements have been described 9.

Leukocytes were characterized on whole blood by polychromatic flow cytometry with 4 antibody panels, namely T-B-NK, regulatory T-cells Treg , Mat, and circulating DCs, as described elsewhere 9 and detailed in Supplementary Information Section 5. IL-7 is a critical T-cell trophic cytokine.

Methods were as described previously 8 , Systemic inflammation was assessed by measuring plasma IL-6 levels using Luminex assays, employing methods described by the manufacturer. Further details are provided in Supplementary Information Section 6. RNA-seq analysis was performed in the designated groups See Supplementary Information section 7.

RNA quantity and purity were determined using an Agilent Bioanalyzer with an RNA Nano assay Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA. Briefly, mRNA was selected using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads and then enzymatically fragmented.

First and second cDNA strands were synthesized and end-repaired. The library with adaptors was enriched by PCR. Libraries were size checked using a DNA high-sensitivity assay on the Agilent Bioanalyzer Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA and quantified by a Kapa Library quantification kit Kapa Biosystems, Woburn, MA.

Base calling and quality filtering were performed using the CASAVA v1. Sequences were aligned and mapped to the UCSC hg19 build of the Homo sapiens genome from Illumina igenomes using tophat v2. Gene counts for 23, unique, well-curated genes were obtained using HTSeq framework v0.

Gene counts were normalized, and dispersion values were estimated using the R package, DESeq v1. The design matrix row — samples; column — experimental variables used in DESeq, along with gene-expression matrix row — genes; column — gene counts in each sample , included the group variable therapy-naïve, HIV—, IHG , CMV serostatus, and the personal identification number, all as factors, and other variables.

Genes with a gene count of 0 across all samples were removed; the remaining zeros 0 were changed to ones 1 and these genes were used in the gene-expression matrix in DESeq.

The size factors were estimated using the gene-expression matrix taking library sizes into account; these were used to normalize the gene counts. Cross-sectional differences between the groups were assessed. The correlation of genes with functional markers T-cell responsiveness, T-cell dysfunction, and systemic inflammation was assessed in a subset of this cohort and is detailed in Supplementary Information Section 7.

Details for deriving transcriptomic signature scores are in Supplementary Information Section 8. From our previous work on immunologic resilience in COVID 6 , 3 survival-associated signatures SAS and 7 mortality-associated signatures MAS were derived from peripheral blood transcriptomes of 48 patients of the COVID cohort.

Of these, the topmost hits in each category SAS-1 and MAS-1 were used in this study. Briefly, a generalized linear model based on the negative binomial distribution with the likelihood ratio test was used to examine the associations with outcomes: non-hospitalized [NH], hospitalized [H], nonhospitalized survivors [NH-S], hospitalized survivors [H-S], hospitalized-nonsurvivors [H-NS], and all nonsurvivors [NS] at days.

NH groups genes associated with hospitalization status , and H-NS vs. H-S genes associated with survival in hospitalized patients were identified. Next, in peripheral blood transcriptomes, genes that were DE between H-S vs.

NH-S, NS vs. H-S, and NS vs. NH-S groups were identified and the genes that overlapped in these comparisons with a concordant direction of expression were examined. This approach allowed us to identify genes that track from less to greater disease severity and vice versa i.

Note: NS in this analysis include both NH and H patients who died. DAVID v6. Based on the differentially expressed genes identified in each comparison and their direction of expression upregulated vs.

The filtering resulted in 51 GO-BP terms 51 sets of gene signatures and 1 signature set of 28 genes, the top 52 gene signatures. Ten signatures overlapped between both cohorts and were further examined. Supplementary Data 9b describes the gene compositions of the 3 SAS and 7 MAS gene signatures.

SASs and MASs were numbered according to their prognostic capacity for predicting survival or mortality, respectively in the FHS [lowest to highest Akaike information criteria; SAS-1 to SAS-3 and MAS-1 to MAS-7] Supplementary Data 9c—d.

The top associated signature in each category SAS-1 and MAS-1 were used in this study as z -scores. SAS-1 and MAS-1 correspond to the gene signature 32 immune response and 4 defense response to gram-positive bacterium , respectively, as detailed in our recent report 6. To generate the z -scores, the normalized expression of each gene is z -transformed mean centered then divided by standard deviation across all samples and then averaged.

High indicates expression of the score in the sample greater than the median expression of the score in the dataset, whereas low indicates expression of the score in the sample less than or equal to the median expression of the score in the dataset.

The profiles detailed statistical methods per figure panel Supplementary Information Sections A list of 57 genes Supplementary Information section 8. The genes significantly and consistently correlated with both age and cell-based IMM-AGE score that predicted all-cause mortality in the FHS offspring cohort Note: the directionality of association of IMM-AGE transcriptomic-based with mortality reported by us in Fig.

The IMM-AGE transcriptomic signature score was examined in different datasets to assess its association with survival. To generate the z -score, the log 2 normalized expression of each gene is z -transformed mean centered then divided by standard deviation across all samples and then averaged.

Details of the publicly available datasets are provided in Supplementary Information Section 8. The broad principles used for the statistical approach are described in Supplementary Information Section 2.

This section provides general information on the study design and how statistical analyses were conducted and are detailed in the statistics per panel section in the Supplementary information.

In addition, each figure is linked with a source document for reproducibility. Furthermore, given the wide range of cohorts and conditions IHGs were examined under, we believe these results to be highly reproducible. Because secondary analyses were conducted, a priori sample size calculations were not conducted.

This was not an interventional study; therefore, no blinding or randomization was used. Reported P values are 2-sided and set at the 0.

The models and P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons in the prespecified subgroup analyses, unless otherwise noted.

All cutoffs and statistical tests were determined pre hoc. The log-rank test was used to evaluate for overall significance.

Details of Pearson vs. Spearman correlation coefficient are provided in Supplementary Information Section Follow-up times and analyses were prespecified. Boxplots center line, median; box, the interquartile range IQR ; whiskers, rest of the data distribution ±1.

Line plots were used to represent proportions of indicated variables. Kaplan-Meier plots were used to represent proportion survived over time since score calculation baseline by indicated groups.

Heatmaps were used to represent correlations of gene signature scores and continuous age. Stacked barplots or barplots were used to represent proportions or correlation coefficients of indicated variables. Pie charts were used to represent proportions of indicated variables. In the COVID cohort, a Cox proportional hazards model, adjusted for sex and age as a continuous variable, was used to determine whether the gene scores associated with day survival.

In the FHS offspring cohort, a Cox proportional hazards model, adjusted for sex and age as a continuous variable, was used to determine whether the gene scores associated with survival. Kaplan-Meier survival plots of the FHS offspring cohort are accompanied by P values determined by log-rank test.

Grades of antigenic stimulation and IR metrics were used as predictors. For determining the association between level of antigenic stimulation and IHG status in HIV— persons, proxies were used to grade this level and quantify host antigenic burden accumulated: 1 age was considered as a proxy for repetitive, low-grade antigenic experiences accrued during natural aging; 2 a BAS based on behavioral risk factors condom use, number of clients, number of condoms used per client and a total STI score based on direct [syphilis rapid plasma reagin test and gonorrhea] and indirect vaginal discharge, abdominal pain, genital ulcer, dysuria, and vulvar itch indicators of STI were used as proxies in HIV— FSWs for whom this information was available; and 3 S.

haematobium egg count in the urine was a proxy in children with this infection. ANOVA-based linear regression model was used to evaluate the overall differences between 3 or more groups.

For comparison of groups with multiple samples from the same individuals, we used a linear generalized estimating equation GEE model based on the normal distribution with an exchangeable correlation structure unless otherwise stated.

For the association of gene scores with outcomes, linear regression linear model was used to test them, instead of nonparametric tests as highlighted below in the panel-by-panel detailed statistical methods for each of the figures.

For comparison of groups with multiple samples from the same individuals, we used a linear GEE model based on the normal distribution with an exchangeable correlation structure unless otherwise stated.

New research shows Boositng risk imkune infection Resiluence prostate biopsies. Discrimination at resiliencw is linked to high blood pressure. Increase Brain Alertness and Engagement fingers Non-prescription emotional balance toes: Poor circulation or Raynaud's phenomenon? How can you improve your immune system? On the whole, your immune system does a remarkable job of defending you against disease-causing microorganisms. But sometimes it fails: A germ invades successfully and makes you sick. Is it possible to intervene in this process and boost your immune system?Boosting immune resilience -

The hallmark of asymptomatic status after intranasal inoculation of respiratory viruses was the capacity to preserve, enrich, or rapidly restore the survival-associated SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile Figs.

Findings noted on longitudinal monitoring of IR degradation and reconstitution during natural infection with common respiratory viruses supported this possibility. During recovery, reconstitution of optimal IR was greater and faster in persons who before infection had the survival-associated SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low vs.

the SAS-1 low -MAS-1 high profile Fig. However, despite the elapse of several months from initial infection, some younger persons with the SAS-1 high -MAS-1 low profile before infection failed to reconstitute this profile exemplifying residual deficits in IR Fig.

An impairment in the capacity for reconstitution of optimal IR was also observed in prospective cohorts with other inflammatory contexts FSWs, COVID, HIV infection. These findings support our viewpoint that the deviation from optimal IR that tends to occur with age could be due to an impairment in the reconstitution of IR in individuals with the IR erosion-susceptible phenotype Fig.

There is significant interest in identifying host genetic factors that mediate resistance to acquiring SARS-CoV-2 or developing severe COVID 59 , 60 , We are currently investigating whether failure to reconstitute optimal IR after acute COVID may contribute to postacute sequelae.

Resistance to HIV acquisition despite exposure to the virus is a distinctive trait 62 observable in some FSWs. Among FSWs with comparable levels of risk factor-associated antigenic stimulation, HIV seronegativity was an indicator of the IR erosion-resistant phenotype, whereas seropositivity was an indicator of the IR erosion-susceptible phenotype.

Having baseline IHG-IV, a nonoptimal IR metric, associated with a nearly 3-fold increased risk of subsequently acquiring HIV, after controlling for level of risk factors.

We found that a subset of FSWs had the capacity for preservation of optimal IR, both before and after HIV infection. By analogy, we suggest that CMV seropositivity may have similar indicator functions Supplementary Notes 3 , 9.

The IR framework points to the commonalities in the HIV and COVID pandemics. Our findings suggest that these pandemics may be driven by individuals who had IR degradation before acquisition of viral infection.

With respect to the HIV pandemic, nonoptimal IR metrics are overrepresented in persons with behavioral and nonbehavioral risk factors for HIV, and these metrics predict an increased risk of HIV acquisition.

Correspondingly, HIV burden is greater in geographic regions where the prevalence of nonbehavioral risk factors is also elevated e. With respect to the COVID pandemic, the proportion of individuals preserving optimal IR metrics decreases with age and age serves as a dominant risk factor for developing severe acute COVID Controlling for age, the likelihood of being hospitalized was significantly lower in individuals preserving optimal IR at diagnosis with COVID Thus, individuals with the IR erosion-susceptible phenotype may have contributed substantially to the burden of these pandemics.

Our study has several limitations expanded limitations in Supplementary Note The primary limitation is our inability to examine the varied clinical outcomes assessed here in a single prospective human cohort. Such a cohort that spans all ages with these varied inflammatory stressors and outcomes is nearly impossible to accrue, necessitating the juxtaposition of findings from varied cohorts.

Additionally, we were unable to evaluate immune traits in peripheral blood samples bio-banked from the same individual when they were younger vs. However, we took several steps to mitigate this limitation discussed in Supplementary Notes 2 , 8.

However, our findings satisfy the nine Bradford-Hill criteria 65 , the most frequently cited framework for causal inference in epidemiologic studies Supplementary Note We acknowledge that, in addition to inflammatory stressors, the changes in IR metrics observed during aging Figs.

Possible confounders regarding the generation of the IHGs and their distribution patterns in varied settings of increased antigenic stimulation are discussed Supplementary Notes 1 , 2 , 3 and 6. While we focused on the association between antigenic stimulation associated with inflammatory stressors and shifts in IHG status, psychosocial stressors may contribute, as they associate with age-related T lymphocyte percentages in older adults However, the latter lymphocyte changes can be indirect, as psychosocial stressors may predispose to infection 68 , As a final limitation, we could not evaluate whether eroded IR mitigates autoimmunity.

Supporting our conclusion that age-independent mechanisms contribute to IR status, we provide evidence that host genetic factors in MHC locus associate with the IR erosion phenotypes Supplementary Note 5.

age Fig. First, while a significant effort is placed on targeting the immune traits associated with age, we show that immune traits group into those associated i uniquely with IR status irrespective of age, ii uniquely with age, and iii both age and IR status Fig.

Some of the immune traits that associate with uniquely nonoptimal IR metrics have been misattributed to age e. Hence, a comparison of immune traits between younger and older persons conflates these groupings, obscuring the immune correlates of age.

Second, the reversibility of eroded IR suggests that immune deficits linked to this erosion are separable from those linked directly to the aging process and may be more amenable to reversal. However, our findings in FSWs and during natural respiratory viral infections indicate that this reversal may take months to years to occur.

Additionally, data from FSWs and sooty mangabeys illustrate that multiple sources of inflammatory stress have additive negative effects on IR status Fig. Hence, reconstitution of optimal IR may require cause-specific interventions. In summary, our findings support the principles of our framework Fig.

Irrespective of these factors, most individuals do not have the capacity to preserve optimal IR when experiencing common inflammatory insults such as symptomatic viral infections. Deviations from optimal IR associates with an immunosuppressive-proinflammatory, mortality-associated gene expression profile.

This deviation is more common in males. Those individuals with capacity to resist this deviation or who during the recovery phase rapidly reconstitute optimal IR manifest health and survival advantages.

However, under the pressure of repeated inflammatory antigenic stressors experienced across their lifetime, the number of individuals who retain capacity to resist IR degradation declines. How might these framework principles inform personalized medicine, development of therapies to promote immune health, and public health policies?

First, individuals with suboptimal or nonoptimal IR can potentially regain optimal IR through reduction of exposure to infectious, environmental, behavioral, and other stressors. Second, IR metrics provide a means to gauge immune health regardless of age, sex, and underlying comorbid conditions.

Thus, early detection of individuals with IR degradation could prompt a work-up to identify the underlying inflammatory stressors. Third, balancing trial and placebo arms of a clinical trial for IR status may mitigate the confounding effects of this status on outcomes that are dependent on differences in immunocompetence and inflammation.

Fourth, while senolytic agents are being investigated for the reversal of age-associated pathologies 75 , the findings presented herein provide a rationale to consider the development of strategies that, by targeting the IR erosion-susceptible phenotype, may improve vaccine responsiveness, healthspan, and lifespan.

Finally, population-level differences in the prevalence of IR metrics may help to explain the racial, ethnic, and geographic distributions of diseases such as viral infections and cancers. Hence, strategies for improving IR and lowering recurrent inflammatory stress may emerge as high priorities for incorporation into public health policies.

All studies were approved by the institutional review boards IRBs at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and institutions participating in this study.

The IRBs of participating institutions are listed in the reporting summary. All studies adhered to ethical and inclusion practices approved by the local IRB.

The cohorts and study groups Fig. The SardiNIA study investigates genotypic and phenotypic aging-related traits in a longitudinal manner. The main features of this project have been described in detail previously 9 , 76 , All residents from 4 towns Lanusei, Arzana, Ilbono, and Elini in a valley in Sardinia Italy were invited to participate.

Immunophenotype data from participants age 15 to years were included in this study. Details provided in Supplementary Information Section 1. The Majengo sex worker cohort 17 is an open cohort dedicated to better understanding the natural history of HIV infection, including defining immunologic correlates of HIV acquisition and disease progression.

The present study comprised initially HIV-negative FSWs with data available for analysis and were evaluated from the time they were enrolled see criteria in Supplementary Fig.

Of these, subsequently seroconverted. The characteristics of these FSWs are listed in Supplementary Data 4a. The association of risk behavior e. Among these, 53 subsequently seroconverted.

Prior to seroconversion, the 53 FSWs were followed for The characteristics of these FSWs are listed in Supplementary Data 4b.

To investigate the associations of IHG status with cancer development, we assessed the hazard of developing CSCC within a predominantly White cohort of long-term RTRs. A total of RTRs with available clinical and immunological phenotype were evaluated.

The characteristics of the RTRs are as described previously 15 and summarized in Supplementary Data 5. Briefly, 65 eligible RTRs with a history of post-transplant CSCC were identified, of whom 63 were approached and 59 participated.

Seventy-two matched eligible RTRs without a history of CSCC were approached and 58 were recruited. Fifteen percent of participants received induction therapy at the time of transplant, and 80 percent had received a period of dialysis prior to transplantation. haematobium urinary tract infection were from a previous study Briefly, all participants were examined by ultrasound for S.

haematobium infection and associated morbidity in the Msambweni Division of the Kwale district, southern Coast Province, Kenya, an area where S. haematobium is endemic. No community-based treatment for schistosomiasis had been conducted during the preceding 8 years of enrollment in this population.

From this initial survey, we selected all children 5—18 years old residing in 2 villages, Vidungeni and Marigiza, who had detectable bladder pathology and S.

haematobium infection. The HIV-seronegative UCSD cohort was accessed from HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center, UCSD, and derived from the following three resources: a those who enrolled as a normative population for ongoing studies funded by the National Institute of Mental Health; b those who enrolled as a normative population for studies funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse; and c those who enrolled as HIV— users of recreational drugs for studies funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

In the present study, we evaluated participants pooled from the three abovementioned sources. This was a prospective observational cohort study of patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 evaluated at the Audie L.

Murphy VA Medical Center, South Texas Veterans Health Care System STVHCS , San Antonio, Texas, from March 20, , through November 15, The cohort characteristics and samples procedures are described in Supplementary Data 2 and Supplementary Data 7. The cohort features of a smaller subset of patients studied herein and samples procedures have been previously described 6.

COVID progression along the severity continuum was characterized by hospitalization and death. Standard laboratory methods in the Flow Cytometry Core of the Central Pathology Laboratory at the Audie L. The overview of this cohort is shown in Supplementary Fig.

All measurements evaluated in the present study were conducted prior to the availability of COVID vaccinations. RNA-Seq was performed on a subset of this cohort as previously described 6. These participants were recruited between June and June and then followed prospectively.

Details of the cohort are as described previously 7. We evaluated only participants in whom an estimated date of infection could be calculated through a series of well-defined stepwise rules that characterize stages of infection based on our previously described serologic and virologic criteria 7.

Of the participants, were evaluated in the present study while they were therapy-naïve see criteria in Supplementary Fig. The inclusion criteria are outlined in Supplementary Fig.

Participants in the cohort self-selected ART or no ART, and those who chose not to start therapy were followed in a manner identical to those who chose to start ART. Rules of computing time to estimated date of infection are as reported by us previously 7.

The US Military HIV Natural History Study is designated as the EIC. This is an ongoing, continuous-enrollment, prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study conducted through the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program.

The EIC has enrolled approximately active-duty military service members and beneficiaries since at 7 military treatment facilities MTFs throughout the United States.

The US military medical system provides comprehensive HIV education, care, and treatment, including the provision of ART and regular visits with clinicians with expertise in HIV medicine at MTFs, at no cost to the patient. Mandatory periodic HIV screening according to Department of Defense policy allowed treatment initiation to be considered at an early stage of infection before it was recommended practice.

Eighty-eight percent of the participants since have documented seroconversion i. In the present study, of EIC participants were available for evaluation Supplementary Fig. Additional details of the SardiNIA 9 , 76 , 77 , FSW-MOCS 17 , PIC-UCSD 7 , RTR cohort 15 , S.

haematobium -infected children cohort 78 , and EIC 8 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 have been described previously. Some features of the entire populations or subsets of the SardiNIA, COVID, SLE Supplementary Information Section 8. One hundred sixty sooty mangabeys were evaluated in the current study.

Of these, 50 were SIV seronegative SIV— and were naturally infected with SIV Figs. Data from a subset of these sooty mangabeys have been reported by Sumpter et al. All sooty mangabeys were housed at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center and maintained in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

In uninfected animals, negative SIV determined by PCR in plasma confirmed the absence of SIV infection. Other immune traits studied are reported in Supplementary Data Forty-seven male and 40 female SIV— Chinese rhesus macaques from a previous study were evaluated Fig.

All animals were colony-bred rhesus macaques M. mulatta of Chinese origin. All animals were without overt symptoms of disease tumors, trauma, acute infection, or wasting disease ; estrous, pregnant, and lactational macaques were excluded.

In a study by Rasmussen et al. Different strains were crossed with one another to generate CC-RIX F1 progeny. We selected those cutoffs based on the following rationale.

Additional details regarding the IHGs are described in Supplementary Note 1. Immune correlates markers that associated with IHG status vs. age in the SardiNIA cohort were assessed on fresh blood samples. A set of multiplexed fluorescent surface antibodies was used to characterize the major leukocyte cell populations circulating in peripheral blood belonging to both adaptive and innate immunity.

Briefly, with the antibody panel designated as T-B-NK in Supplementary Data 12 , we identified T-cells, B-cells, and NK-cells and their subsets. We also used the HLA-DR marker to assess the activation status of T and NK cells.

The regulatory T-cell panel Treg in Supplementary Data 12 was used to characterize regulatory T-cells subdivided into resting, activated, and secreting nonsuppressive cells 96 , Moreover, in selected T-cell subpopulations, we assessed the positivity for the ectoenzyme CD39 and the CD28 co-stimulatory antigen Finally, by the circulating dendritic cells DC panel, we divided circulating DCs into myeloid conventional DC, cDC and plasmacytoid DCs pDC and assessed the expression of the adhesion molecule CD62L and the co-stimulatory ligand CD86 , The circulating DC panel is labelled DC in Supplementary Data Detailed protocols and reproducibility of the measurements have been described 9.

Leukocytes were characterized on whole blood by polychromatic flow cytometry with 4 antibody panels, namely T-B-NK, regulatory T-cells Treg , Mat, and circulating DCs, as described elsewhere 9 and detailed in Supplementary Information Section 5.

IL-7 is a critical T-cell trophic cytokine. Methods were as described previously 8 , Systemic inflammation was assessed by measuring plasma IL-6 levels using Luminex assays, employing methods described by the manufacturer. Further details are provided in Supplementary Information Section 6.

RNA-seq analysis was performed in the designated groups See Supplementary Information section 7. RNA quantity and purity were determined using an Agilent Bioanalyzer with an RNA Nano assay Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA.

Briefly, mRNA was selected using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads and then enzymatically fragmented. First and second cDNA strands were synthesized and end-repaired.

The library with adaptors was enriched by PCR. Libraries were size checked using a DNA high-sensitivity assay on the Agilent Bioanalyzer Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA and quantified by a Kapa Library quantification kit Kapa Biosystems, Woburn, MA. Base calling and quality filtering were performed using the CASAVA v1.

Sequences were aligned and mapped to the UCSC hg19 build of the Homo sapiens genome from Illumina igenomes using tophat v2. Gene counts for 23, unique, well-curated genes were obtained using HTSeq framework v0. Gene counts were normalized, and dispersion values were estimated using the R package, DESeq v1.

The design matrix row — samples; column — experimental variables used in DESeq, along with gene-expression matrix row — genes; column — gene counts in each sample , included the group variable therapy-naïve, HIV—, IHG , CMV serostatus, and the personal identification number, all as factors, and other variables.

Genes with a gene count of 0 across all samples were removed; the remaining zeros 0 were changed to ones 1 and these genes were used in the gene-expression matrix in DESeq. The size factors were estimated using the gene-expression matrix taking library sizes into account; these were used to normalize the gene counts.

Cross-sectional differences between the groups were assessed. The correlation of genes with functional markers T-cell responsiveness, T-cell dysfunction, and systemic inflammation was assessed in a subset of this cohort and is detailed in Supplementary Information Section 7.

Details for deriving transcriptomic signature scores are in Supplementary Information Section 8. From our previous work on immunologic resilience in COVID 6 , 3 survival-associated signatures SAS and 7 mortality-associated signatures MAS were derived from peripheral blood transcriptomes of 48 patients of the COVID cohort.

Of these, the topmost hits in each category SAS-1 and MAS-1 were used in this study. Briefly, a generalized linear model based on the negative binomial distribution with the likelihood ratio test was used to examine the associations with outcomes: non-hospitalized [NH], hospitalized [H], nonhospitalized survivors [NH-S], hospitalized survivors [H-S], hospitalized-nonsurvivors [H-NS], and all nonsurvivors [NS] at days.

NH groups genes associated with hospitalization status , and H-NS vs. H-S genes associated with survival in hospitalized patients were identified.

Next, in peripheral blood transcriptomes, genes that were DE between H-S vs. NH-S, NS vs. H-S, and NS vs. NH-S groups were identified and the genes that overlapped in these comparisons with a concordant direction of expression were examined.

This approach allowed us to identify genes that track from less to greater disease severity and vice versa i. Note: NS in this analysis include both NH and H patients who died.

DAVID v6. Based on the differentially expressed genes identified in each comparison and their direction of expression upregulated vs. The filtering resulted in 51 GO-BP terms 51 sets of gene signatures and 1 signature set of 28 genes, the top 52 gene signatures.

Ten signatures overlapped between both cohorts and were further examined. Supplementary Data 9b describes the gene compositions of the 3 SAS and 7 MAS gene signatures. SASs and MASs were numbered according to their prognostic capacity for predicting survival or mortality, respectively in the FHS [lowest to highest Akaike information criteria; SAS-1 to SAS-3 and MAS-1 to MAS-7] Supplementary Data 9c—d.

The top associated signature in each category SAS-1 and MAS-1 were used in this study as z -scores. SAS-1 and MAS-1 correspond to the gene signature 32 immune response and 4 defense response to gram-positive bacterium , respectively, as detailed in our recent report 6. To generate the z -scores, the normalized expression of each gene is z -transformed mean centered then divided by standard deviation across all samples and then averaged.

High indicates expression of the score in the sample greater than the median expression of the score in the dataset, whereas low indicates expression of the score in the sample less than or equal to the median expression of the score in the dataset.

The profiles detailed statistical methods per figure panel Supplementary Information Sections A list of 57 genes Supplementary Information section 8. The genes significantly and consistently correlated with both age and cell-based IMM-AGE score that predicted all-cause mortality in the FHS offspring cohort Note: the directionality of association of IMM-AGE transcriptomic-based with mortality reported by us in Fig.

The IMM-AGE transcriptomic signature score was examined in different datasets to assess its association with survival. To generate the z -score, the log 2 normalized expression of each gene is z -transformed mean centered then divided by standard deviation across all samples and then averaged.

Details of the publicly available datasets are provided in Supplementary Information Section 8. The broad principles used for the statistical approach are described in Supplementary Information Section 2. This section provides general information on the study design and how statistical analyses were conducted and are detailed in the statistics per panel section in the Supplementary information.

In addition, each figure is linked with a source document for reproducibility. Furthermore, given the wide range of cohorts and conditions IHGs were examined under, we believe these results to be highly reproducible.

Because secondary analyses were conducted, a priori sample size calculations were not conducted. This was not an interventional study; therefore, no blinding or randomization was used. Reported P values are 2-sided and set at the 0.

The models and P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons in the prespecified subgroup analyses, unless otherwise noted.

All cutoffs and statistical tests were determined pre hoc. The log-rank test was used to evaluate for overall significance. Details of Pearson vs. Spearman correlation coefficient are provided in Supplementary Information Section Follow-up times and analyses were prespecified.

Boxplots center line, median; box, the interquartile range IQR ; whiskers, rest of the data distribution ±1. Line plots were used to represent proportions of indicated variables. Kaplan-Meier plots were used to represent proportion survived over time since score calculation baseline by indicated groups.

Heatmaps were used to represent correlations of gene signature scores and continuous age. Stacked barplots or barplots were used to represent proportions or correlation coefficients of indicated variables. Pie charts were used to represent proportions of indicated variables.

In the COVID cohort, a Cox proportional hazards model, adjusted for sex and age as a continuous variable, was used to determine whether the gene scores associated with day survival. In the FHS offspring cohort, a Cox proportional hazards model, adjusted for sex and age as a continuous variable, was used to determine whether the gene scores associated with survival.

Kaplan-Meier survival plots of the FHS offspring cohort are accompanied by P values determined by log-rank test. Grades of antigenic stimulation and IR metrics were used as predictors. For determining the association between level of antigenic stimulation and IHG status in HIV— persons, proxies were used to grade this level and quantify host antigenic burden accumulated: 1 age was considered as a proxy for repetitive, low-grade antigenic experiences accrued during natural aging; 2 a BAS based on behavioral risk factors condom use, number of clients, number of condoms used per client and a total STI score based on direct [syphilis rapid plasma reagin test and gonorrhea] and indirect vaginal discharge, abdominal pain, genital ulcer, dysuria, and vulvar itch indicators of STI were used as proxies in HIV— FSWs for whom this information was available; and 3 S.

haematobium egg count in the urine was a proxy in children with this infection. ANOVA-based linear regression model was used to evaluate the overall differences between 3 or more groups. For comparison of groups with multiple samples from the same individuals, we used a linear generalized estimating equation GEE model based on the normal distribution with an exchangeable correlation structure unless otherwise stated.

For the association of gene scores with outcomes, linear regression linear model was used to test them, instead of nonparametric tests as highlighted below in the panel-by-panel detailed statistical methods for each of the figures.

For comparison of groups with multiple samples from the same individuals, we used a linear GEE model based on the normal distribution with an exchangeable correlation structure unless otherwise stated. For meta-analyses e.

All datasets were filtered for common probes. Then, an expression matrix of the probes and samples was created and concurrently normalized as stated in Supplementary Information Section 9.

Example: if dataset 1 provided log 2 values and dataset 2 was quantile normalized, dataset 1 would be un-log transformed by exponentiation with the base 2 before combining with dataset 2 for concurrent normalization and computation of scores.

The phenotype groups for plots were determined from the phenotype data deposited in the GEO or ArrayExpress along with the dataset.

The phenotype groups were classified based on the hypothesis evaluated. The transcriptomic signature score is a relative term within a dataset, and it is challenging to compare the score across different datasets. For the meta-analyses, we used a series of criteria as described in Supplementary Information Section 9.

Different RNA microarray or RNA-seq platforms have differences in the availability of gene probes corresponding to the genes in a given transcriptomic signature score.

Thus, we indicated the gene count range in each dataset Supplementary Data 13b. As the overall median IQR percentage of available genes is high, In addition, we stress that transcriptomic signature scores were defined in relative terms and caution is needed for cross-dataset comparisons.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article. Individual level raw data files of the VA COVID cohort cannot be shared publicly due to data protection and confidentiality requirements. South Texas Veterans Health Care System STVHCS at San Antonio, Texas, is the data holder for the COVID data used in this study.

Data can be made available to approved researchers for analysis after securing relevant permissions via review by the IRB for use of the data collected under this protocol. Inquiries regarding data availability should be directed to the corresponding author. Accession links to all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in Supplementary Data 13a.

Source data are provided with this paper. p11 , phs Aggregate data presented for these cohorts in the current study are provided in the source data file. Immunophenotyping data from the SardiNiA cohort used in Fig. doi: Data from RTRs are derived and sourced from Bottomley et al.

The sources of the data for the literature survey Fig. html ] was used for download and analyses of GEO datasets, and a script from vignette of ArrayExpress R package was used for download and analyses of ArrayExpress datasets. The scripts are available from the corresponding author on request.

Klunk, J. et al. Evolution of immune genes is associated with the Black Death. Nature , — Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

Klein, S. Sex differences in immune responses. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Austad, S. Sex differences in lifespan. Cell Metab. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

Takahashi, T. Sex differences in immune responses that underlie COVID disease outcomes. Gebhard, C. Impact of sex and gender on COVID outcomes in Europe. Lee, G. Immunologic resilience and COVID survival advantage. Allergy Clin. Le, T. Okulicz, J.

Influence of the timing of antiretroviral therapy on the potential for normalization of immune status in human immunodeficiency virus 1-infected individuals. JAMA Intern Med. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

Orru, V. Genetic variants regulating immune cell levels in health and disease. Cell , — Mahmood, S. The Framingham Heart Study and the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease: a historical perspective.